Mary Elizabeth Phillips was the reluctant media star of San Francisco’s eviction epidemic. And now, she has quietly passed into the vibrant history of the town she fell in love with nearly 80 years ago.

55 Dolores Street could be described as post-war modern, unadorned and clean of line. At the time it was built it may have appeared jarring, wedged between an auto garage from 1918 and an apartment house festooned with bas-relief. Yet today, the building looks meek and human-scaled, seeming to deflect attention as it falls within the literal shadow of its new neighbor across the street.

38 Dolores is an attention vortex, a PoMo du jour behemoth with a busy parking garage and Whole Foods Market. Its premises offer a vegetable garden for residents and a butterfly habitat, presumably for butterflies.

55 Dolores sits quietly now—a four-level ghost town with no gardens or habitats. Emptied of tenants, it has been haunted by uncertainty for more than three years as a conversion from modest apartments into homes for the wealthy ground to an ignominious halt. The building’s last remaining resident, retired accountant Mary Elizabeth Phillips, was a monkey wrench personified. By refusing to leave, she unwittingly threw herself on an engine of profit and stalled its gears. And the only troubling detail that delayed her forcible removal from her long-time home was that Mary Elizabeth (“M.E.” or “Emmy”) happened to be 97 years old. Recently, Ms. Phillips died peacefully, still in her home, at age 100.

The 55 Dolores building was not a place I visited in order to write a story. I’m not a journalist. I went there because I happened upon Ms. Phillips in the media and was deeply touched by her predicament. I learned that the new owner of the building, Urban Green Investments, a real estate investment firm that was snapping up buildings in San Francisco, cleansing them of tenants then flipping the properties for untold profits, held the answer to her future. I further parsed that, speculator compassion being as scarce as affordable housing, prospects for keeping Emmy in her beloved home appeared to be questionable.

What I had inadvertently stumbled into was a primer on predatory greed, of diminishing time and its consequences. I wondered how San Franciscans had become so acclimated to a tech-fueled cultural declension we could allow a 97-year-old woman to be kicked to the curb as mere collateral damage. Eviction Free San Francisco, a direct action group that had taken on Emmy’s case, made contact with her on my behalf. Like many, I was reeling from the latest boom’s sucker punch, having seen too many loved ones forced from their homes, anxious about the security of my own. And as a neighbor, I felt the least I could do was offer my support in any way possible. But first, I wrote Emmy a letter.

A month later, on a Sunday afternoon, I found a lilting voice on my answering machine. “Hello, Ron. This is Emmy Phillips, the little old lady at 55 Dolores? I do hope you’re out enjoying the lovely day. Please call and perhaps come over for a visit sometime.” I took her up on it, ringing her bell nearly every Sunday afternoon for the two-and-a-half years before her death.

As initial impressions are the most deeply etched, her former neighbor, Sarah Brant, once told me about her introduction to Emmy—a highly evocative story of the woman I would come to know. Emmy, then in her 80s, answered her door in leopard print and a wig sitting slightly askew. She was ready to go out dancing, and would prod her new young neighbor thereafter. “Why don’t you go out dancing all night? You don’t even need to wear a wig.”

My inaugural visit to Emmy was perhaps less dramatic, though no less striking. She was standing in the doorway wearing her teal green housecoat and pink slippers as I climbed the stairs. I thought, wow, not even Betty White could offer a more beautifully impish grin. Her cozy apartment was redolent of personal history and assiduously lived-in, though Emmy’s cherry tomato plants on the balcony may have appreciated a decent watering.

There was a casual ease to a visit with Emmy, perhaps bespeaking her Southern origins. “Take off your shoes and kick up your feet.” Louisiana was still there, in her voice. “I never tried to lose my accent or hold onto it,” she explained about adjusting to West Coast life decades ago. The Golden Gate Bridge opened to great fanfare the year of her arrival. Mention it and she’d light up as though the celebration never ended.

In her living room of a mostly Asian motif, I often felt pleasantly enclosed within a snow globe, and when it was gently shaken, the snowflakes were memories. This one touched down and melted into a story. Then that one and that one. We shared a slowly swirling, nonlinear world as she spoke of the gravel roads of her childhood, of Buick touring cars and Isen glass. Or just as easily, her nice shrimp salad at The Ramp after testifying in Sacramento supporting Senator Mark Leno’s Ellis Act reform bill. I was reminded that this is how two people got to know each other—by catching snowflakes.

She could recall the dawn of the radio era and silent movies—the kiddie shows of Tom Mix, the Lone Ranger, and Rin Tin Tin. She remembered being awed by the first talkie, “The Jazz Singer.” She even mimicked Al Jolson to prove it. I asked what else she did for entertainment as a kid. “Get in trouble,” she waggishly snapped. Being somewhat of a tomboy, she liked climbing trees. Once, her mother had to coax her down from the top of a telephone pole.

She confided in me a strange incident that had haunted her for decades. As a young woman driving alone through a storm, she was alarmed when small frogs began raining from the sky! “I suspect people think I’m crazy, but I know what I saw.” Emmy, out-of-the-loop internet-wise, implored me, “Put that in your computer, will you?” I did. Though rare, there is actually a natural phenomenon called “amphibious rain.” The relief was palpable when I told her.

As a teenaged member of the Young Democrats of America, she and her girlfriends once crashed a political convention. As they were driving back home across northwestern Texas, a young couple parked by the side of the road flagged them down. “They were attractive and very polite,” recalled Emmy, “and also, very lost.” The girls helped direct them and continued on their journey home. The following day, Emmy experienced an arresting shock as a newspaper caught her eye. A photo of the lost young couple was featured on page one, identifying them as Bonnie and Clyde, the notorious Depression-era outlaws.

This was where Emmy might interrupt herself, brushing the air, dismissing the past. “Enough about me! Tell me about you. What was your week like?” Perhaps I’d gulp. “Sweetheart. Please don’t expect me to follow that!” But she was doggedly inquisitive and keenly observant. I brought her photos from my childhood. “I see suspicion in your face here, but also as though you’re ready to break into laughter. Look, you and your friend are wearing the same color socks.” I’d never noticed.

I spoke of my hometown, San Diego. “A lovely place,” she said. During the War she and some girlfriends once visited by hitchhiking. In a moment worthy of a Preston Sturges movie, Emmy and friends hid in the bushes while the most becoming of them stood on the street waving a glove. The man who stopped for her was mightily impressed when the other women jumped from the bushes. But they all got a ride. When I mentioned my mom in San Diego, Emmy asked with a wink in her voice, “Does she know you have a 98-year-old girlfriend?”

Then I ruined everything. I told her my tragic pet rabbit story. She burst into tears. I apologized. She shrugged it off. Note to self: don’t make Emmy cry. But when I asked what took her to Hawaii once for a year, she mentioned her first husband, a Navy pilot, who was stationed at Pearl Harbor during the attacks and was not heard from for five days. He once told her that they should retire to Hawaii some day. Later in the war, she related, he was lost at sea, perhaps shot down by a Japanese Zero. Then she wept.

I suspect Emmy didn’t cry often, and she certainly wouldn’t have shed tears when speaking of Urban Green Investments, her new landlords, who’d bought out or Ellised her neighbors, before evoking less strident methods to expedite her removal. She preferred to express her feelings about them succinctly. “Those bastards!”

I didn’t feel it my place to broach the subject of eviction with Emmy, who had no surviving blood family and no local relations. If she wished to mull over her dilemma, I was there to listen. But she had little tolerance for sympathy. She just wanted to stay in her home. “I’m not moving. I’m too old to move. Where would I go? They’ll have to take me out, feet first.”

By then Emmy had burned through the calendar, using up her year-long senior eviction deferral. The unthinkable now loomed—that Urban Green might call forth their legal cudgel to dispatch her. Eviction Free San Francisco rallied to Emmy’s defense, as they had when her case was first publicized. A group of activists stormed Urban Green’s offices only to find them shuttered. A spirited proxy protest sprung up on the street outside. KRON 4 news aired Emmy’s story that evening. The piece went viral and public outcry was swift. Notoriously mute, Urban Green CEO David McClosky, was finally forced to make a public statement. Emmy would be allowed to stay in her home for the remainder of her life.

Behind the scenes, however, Emmy’s last remaining neighbor and unofficial caregiver, Ms. Brant, was quietly evicted through the Ellis Act, after a protracted legal battle. Friends and allies were concerned that Emmy would still face what amounted to a de facto eviction, as she was now alone with many of her basic needs unmet. Soon too, the building would literally be coming down around her as renovations were scheduled to proceed despite her presence. It appeared to be an untenable situation and that Urban Green would get her out after all, fortuitously minus the negative publicity.

Those of us in Emmy’s life began approaching her caregiving as a distillate of basics. Schedules were created, frequent visits ensued. Lights were kept on and the building’s entryway diligently swept in an effort to make the property appear to be actively inhabited. Nonetheless, break-ins weren’t unheard of. Eventually, round-the-clock care was enlisted.

I was more than happy to help Emmy forget about a world that was encroaching on her own, in the various forms it took. Since I visited on Sundays, though, I didn’t experience the construction noise from next door during the week. The old auto garage and its neighbor, of slightly younger vintages than Emmy, had been razed to make room for yet more luxury condominiums. And finally, renovations on her building commenced, the noise said to be often unbearable.

But my arrivals brought with them the mundane nuggets from the outside world she craved. “Chilly today,” I might say in June. She’d grin. “We do have the most precocious weather.” Though ever-reliable memories were aroused during my visits, Emmy was firmly engaged with the present, following the news and politics (she held a political science degree from LSU). She loved travel, nature and history shows. I found her watching the World Cup on at least two occasions. One moment she might give me a discourse on the Cold War and Vietnam then would suddenly ask, “How do you feel about the situation in Iraq?” Our conversations flowed along like this—lovely streams-of-consciousness. She once learned to fly a Piper Cub. “Easier than driving a car.” She used to zip around the Sacramento River delta in a speedboat. “Exhilarating.” She smoked pot once. “Didn’t feel a thing.”

She showed me a yellowed newspaper clipping of her with a prize-winning bass. “What do you do with a fish that big?” I asked. “I’ll tell you what you do. You make Gefilte Fish.” Emmy got the recipe from the wife of a Jewish gentleman who used to manage the men’s clothiers in the old White House department store downtown (now a Banana Republic). She loved to talk about food, sharing her recipe for tomatoes sautéed in butter and brown sugar, listing all her Southern favorites, and expressing her affection for local Dungeness crab. She once ate snake but didn’t care for it much, and had a marked distaste for “ersatz” whipped cream on her Thanksgiving pumpkin pie. She startled me on one occasion by asking, “If you were going to be executed tomorrow, what dinner would you ask for tonight?” Her choice would be two thin slices of prime rib, Yorkshire pudding and a baked potato.

It didn’t take long for me to discover her true weakness, though. Every Sunday I brought her a box of cream puffs from the Thorough Bread bakery on Church Street.

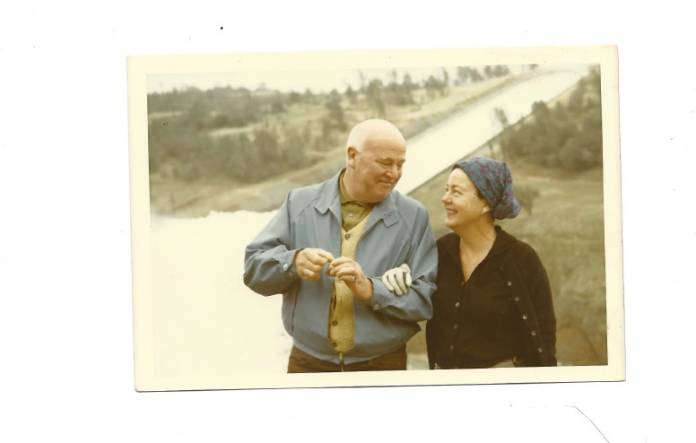

A narrowly averted food disaster played a key role in Emmy’s introduction to a dashing Englishman named John Phillips. At a crowded party, John’s only option for seating was a small stool next to Emmy. As he sat, the stool crumpled beneath him. With instant grace, Emmy caught his plate, then peered down at John on the floor and, not knowing what else to say, asked, “You play bridge?” They would be married within the year, her union with John being the last of three happy marriages.

The couple loved to travel, once living in Mallorca, and briefly, England. John seemed to have influenced Emmy in various loving ways. I heard him summoned when she called men “chaps,” or joked, “How about a spot of tea, old boy?” Being the wife of an Englishman reminded Emmy of her beloved Winston Churchill, whom she credited with saving the Western world from “Mr. Hitler” with his stirring rhetoric. In a sonorous impression of the former U.K. Prime Minister, she’d rear out of her chair, and in a booming voice, paraphrased a famous speech, “We shall fight them on the land and on the sea! We shall fight them in the fields and the streets! We shall never surrender!” Though I could do it no justice, I whispered these same words in Emmy’s ear while she lay gently smiling on her deathbed.

Emmy lived more than half her life in her Dolores Street apartment. Her home seemed to have almost imprinted itself on her DNA. Countless strands of emotional bonding fused her with this place, strengthening as the decades passed. She had pretty much shared the entire time she would have with John Phillips there, and every one of her cherished cat, Ginjo’s, nine lives.

I’d do Emmy’s memory a presumptive disservice if I tried to sum up her years in this apartment. My friendship with her was a work-in-progress. But having known her just some, I would venture this—that her home was a perch from which to observe her city change irrevocably around her, perhaps a crash pad from a night of dancing, a theater of frivolity and a temple of contemplation. Having to leave it involuntarily would’ve, in a way, been like parting from John all over again. Within those walls, the quiet grace of Emmy’s life unfolded and continued to do so, until she left us most voluntarily. She was, after all, still collecting snowflakes.

In getting to know Emmy, I’d been allowed to put a face to displacement. Here was a woman who’d been a San Francisco resident nearly half the city’s history since the Gold Rush, who missed putting on dress gloves to shop at the City of Paris department store, who beheld Montgomery Street buried in a “snow storm” of ticker tape on V-J Day, and who canned Bay oysters before they practically became extinct.

But she’d be the first to nudge us back to a mildly dissonant present. She enjoyed telling me where to go in San Francisco to cut a rug (her favorite dance being the tango), have a swell cocktail and an impeccable meal. Of course, this San Francisco mostly no longer existed and she knew it, though its ghostly imprint still haunted her vast oral history. But aside from a few anecdotes she happily shared, Emmy had no interest in committing her life to the page. She cautioned, however, “Keep a journal and write in it every evening. It will mean something to you someday.”

I often thought of oral history when I was with Emmy. And I was reminded that, of those who have faced the same crossroads as she, there are scores who’ve been given no voice. The media has not picked up their stories, perhaps only alluding to them statistically. They are forced from their homes and often seem to vanish. But like Emmy, it is they who are the embodied genetic material of this town, having animated a once richly diverse community.

It is appropriate to stress that Emmy defied her eviction simply out of common sense. This was her home. There was no point in leaving it, especially at her age. She was also a pragmatist who understood the desire to make a return on one’s investment, though felt Urban Green’s obdurate attempt to cash in on her removal was “just heartless,” and antithetical to any rules of morality she’d even known. Though Urban Green ultimately yielded to public pressure and allowed her to stay at 55 Dolores, Emmy never again felt quite secure there. She’d become an accidental activist and local personality, whose militant line in the sand tenants everywhere had begun to draw, having collectively balked at being dismissed and devalued, angered for being rebranded as transient caretakers for rich people’s future abodes.

One of the last times I saw Emmy she was happily perched in front of a Giants game. She remarked on my new shoelaces, irrelevant though they were. She moaned in joy at her cream puff and we spoke of the election. She was thrilled to live long enough cast her vote and see the first woman president take office. Her time ran out just prior to the hopeful day, and she would’ve been crushed to see “Mr. Trump” prevail as president-elect.

At Emmy’s, clocks did tick—one on my visits each week, one maintained by Urban Green Investments, and others of more personal mechanics. Though her orientation was mostly positive, I often wondered what Emmy felt in her private moments. These emotions were hers alone. In the meantime, her friends and caregivers arrived to offer the security of love, respect and sustenance.

I still have a post-it stuck to my desk with a phone number on it. As Emmy was carefully placing me in her address book after our first meeting, she seemed suddenly perplexed. “I have the number for the White House here. I wonder why. Would you like it?” “Why not?” I piped. Then she giggled. “You never know when it might come in handy.”

I am deeply grateful to Mary Elizabeth Phillips for inviting me into her home and life. I am humbled by her generosity and trust, and feel honored to have been considered a friend and ally. This story, written with her approval mostly before her death, has been the result of her unflagging good will. It was her wish that I put it forth at her passing.

Ron Winter has been a San Francisco Mission resident for 25 years, a mere hiccup of time to a seasoned San Franciscan like Emmy. Ron is most often a writer of fiction. The above story contains no fiction.

IMHO, middle class in SF can be a very wide net of salaries. It’s pretty much been bad since Feinstein was in & she made him very very rich through her machinations.

I hope you sold your fixer upper in McLaren Park & moved up in the world. It’s probably worth a lot more now.

Although SF was relatively less expensive in the pre-Feinstein years, many of us who were renters did not foresee the future when doing our rent vs. buy calculations and couldn’t have predicted the meteoric rise in housing prices and rents. In my situation, although I had a middle-class income working in nonprofits, I never had sufficient savings for a down payment, despite not spending my earnings on dining out, traveling, etc. When I was Ellis evicted after nearly 30 years in my apartment in 1999, I was only able to buy a less than 800 sq foot fixer-upper near McLaren Park because of a small inheritance.

Nice article. Thanks for sharing.

Guilty? Whoa just take it up to 11. It is odd that someone making that kind of money, and advising people on how to invest their money would not have bought anything in SF or even in the South where she was from.

Relying on the transitory nature of the renter relationship. Thats not to say that ownership doesn’t have its vulnerabilities. But ownership is the preferred long-term position – less transitory, if you will. Anyway, I’m sure she got her money’s worth.

So she didn’t buy a place. She’s guilty of what, exactly?

She sounds like a great person, but I’m wondering in the article this was written “The building’s last remaining resident, retired accountant Mary Elizabeth Phillips”.

She was an accountant, so, wondering why she never bought a place, when SF was cheap (anything before Feinstein got into office actually, as SF was pretty cheap to live in then)

The property at 55 Dolores has six units according to the SF Planning property information website. How many years did the units sit vacant? We have a housing crisis in the City and we have available units that could house citizens. That’s a crime on humanity. The City should do something about this.

Thank you so much Mr. Winter, for sharing this precious story about your friendship with Emmy. You’re a very fortunate young man.

Great stories. Sounds like a wonderful woman. I wonder what she was paying for rent?