I’m glad the Chron weighed in, however briefly, on the commemoration of the I-Hotel evictions, although the editorial the paper ran was embarrassing:

San Francisco has moved on. Terms such as Manhattanization and gentrification are realities, not projections.

But the mainstream coverage of the evictions makes it appear as if this was just one of those things, real-estate interests vs. tenants, something of the past.

That ignores the reality that San Francisco politicians, including then-Mayor and now Sen. Dianne Feinstein, allowed the Fall of the I-Hotel, as filmmaker Curtis Choy describes it, to happen.

The tenants of the I-Hotel, the center of Manilatown and the Filipino community in SF, fought eviction attempts going back to the late 1960s, when the owner, Milton Meyer and Co. (run by the famous Democratic Party mega-donor Walter Shorenstein) tried to throw everyone out to build a parking garage.

But after community pressure, Shorenstein agreed to let the tenants stay.

Then in 1974, a group called Four Seas Investment bought the building.

Four Seas was a dummy corporation set up, as the Bay Guardian would later show, by a shadowy liquor baron from Thailand named Supasit Mahaguna. Mahaguna had no interest in the hotel; he just wanted to get his capital out of Thailand.

After a Guardian reporter in Thailand exposed the story, with the cover headline “The Thai Godfather Behind the I-Hotel,” things got a little dicey and the reporter had to leave the country.

The eviction battle was in the courts and in the streets. After the courts approved the eviction, Sheriff Richard Hongisto refused to carry it out; he was held in contempt of court and spend five days in his own jail before he relented and agreed to toss out the tenants.

One of the reasons he backed down, he later told me, was the the city attorney at the time, a rabidly pro-development and pro-landlord guy named George Agnost, had informed Hongisto that the city wouldn’t defend him in any legal claim by Mahaguna — that is, if the building owner sued the city claiming Hongisto had cost him money by failing to evict the tenants, the young sheriff would be on his own. And in fact, Mahaguna sued Hongisto personally for $1 million.

Hongisto became fairly rich later in life from his real-estate investments, but at the time that was a scary threat. Not excusing Hongisto, but Agnost clearly played a role in helping the eviction.

More than 3,000 people were on hand when Hongisto and his troops dragged the last remaining tenants out of the building on Aug. 4, 1977. In the latest Tom and Tim Show, Tom Ammiano, then a young activist, remembers that all sorts of political factions in the city came together to oppose the eviction; they were standing with arms linked to block the sheriffs when a phalanx of police horses charged at the lines. It was terrifying, and ultimately, the cops and the sheriffs broke the blockade.

But the next stage of the battle was at City Hall. Shortly after the eviction, Four Seas set about trying to demolish the I-Hotel — and that required the Board of Appeals to sign off.

Some critical background, drawn from Guardian stories at the time:

In 1976, when George Moscone was mayor, the city offered to work with the International Hotel Tenants Association to buy the property and turn it over for tenant management.

Meanwhile, Four Seas had applied for a demolition permit, which had been approved, but those permits don’t last forever, and in March, 1976, the Board of Appeals voted that the permit had expired and was no longer valid.

After the eviction, Four Seas went to court to challenge that decision and convinced Judge Byron Arnold — himself a landlord and real-estate investor — that the demolition could go forward. Arnold agreed, and ordered the Board of Appeals to rescind that vote and approve the permit.

But on Jan. 3, 1979, several Board members — including David Scott, who would later run for mayor against Feinstein, Agripino Cerbatos, and Doug Engmann — refused to go along. They defied the judge and said they wouldn’t agreed to let Four Seas tear the place down.

During all of this, the city was still officially on record wanting to buy the building, and the tenants believed that if they could stave off demolition, they might still have a chance.

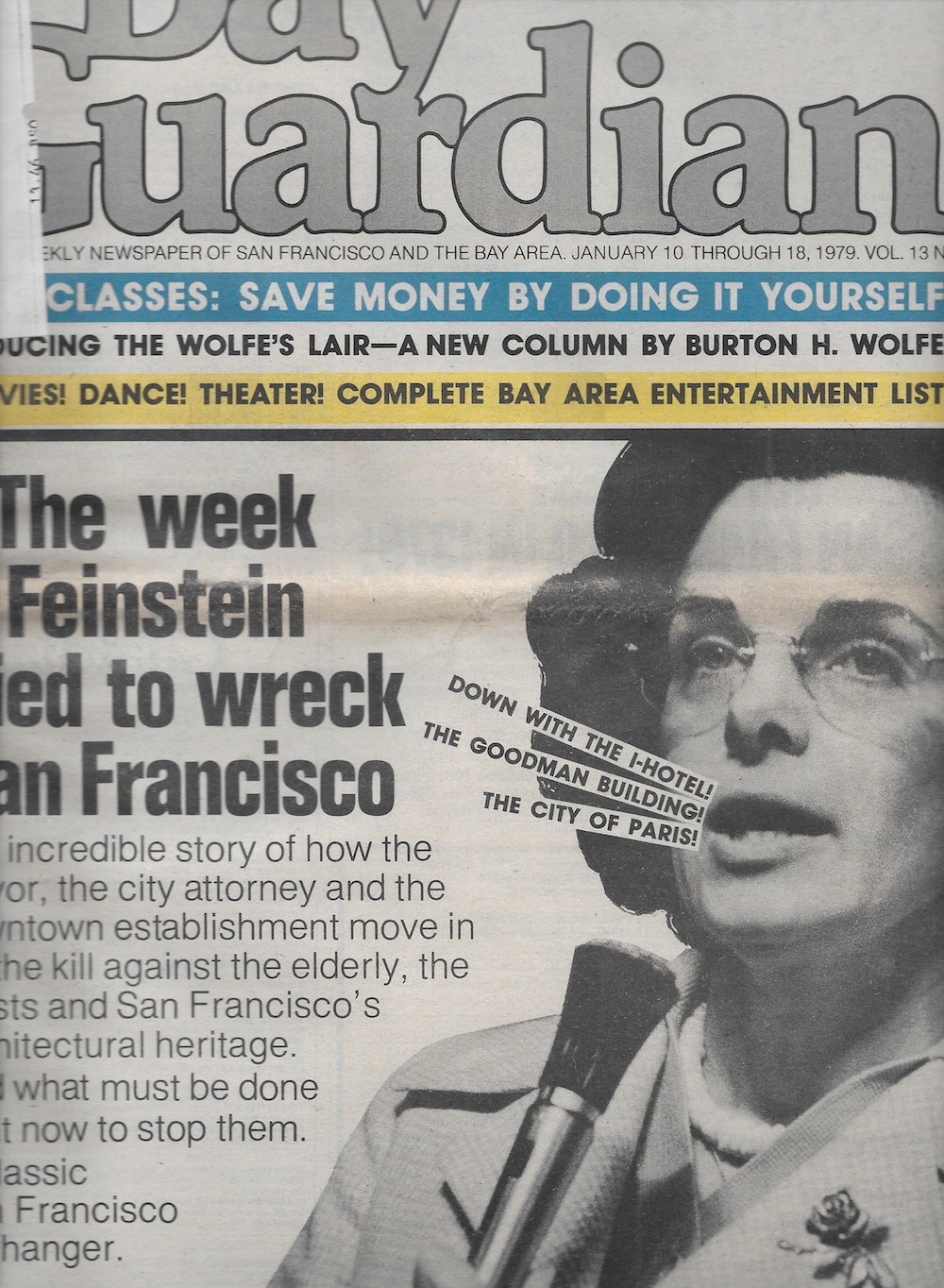

The mayor by then was Feinstein, who took office after the assassinations of Harvey Milk and George Moscone. And Feinstein was absolutely, 100 percent on the side of Four Seas.

On Jan. 4, Feinstein summoned the Board of Appeals members into her office, where Agnost was present, and with the mayor’s support, he gave the commissioners the facts of life: If they refused to approve the demolition, they would be guilty of contempt of court and could be jailed and held liable in a lawsuit.. They he told them the same thing he told Hongisto: The city would not defend them. Even though they were acting in their role as city officials, the City Attorney’s Office would toss them to the wolves.

On Jan. 8, the board voted 4-0 to censure Agnost for failing to uphold his duties to defend city officials and to protect the city’s official policy of saving the I-Hotel. Then, under duress and with no choice, they voted to do what Judge Arnold had ordered.

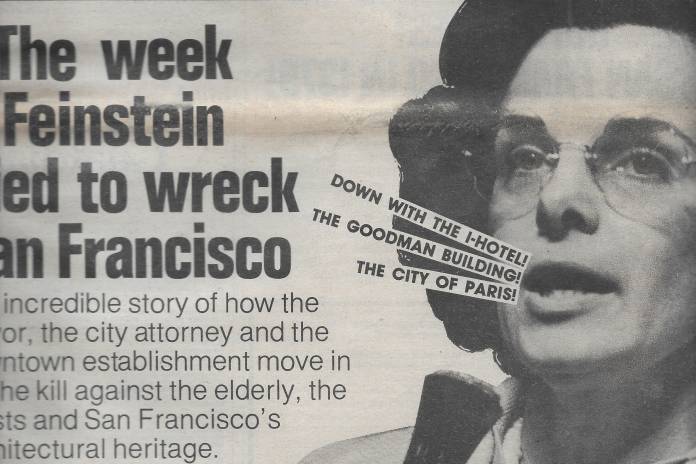

As the Guardian wrote Jan. 11, 1979:

This was the week that showed how things really work in San Francisco. This was the week when Mayor Dianne Feinstein, City Attorney George Agnost, the judiciary, and most elected legislators in town joined in a solid front with the downtown forces and their big law firms, to declare, in effect, Down with the International Hotel.

And of course, the I-Hotel was demolished, and remained a hole in the ground for more than 20 years, a reminder of the failure of the city’s housing policies.

It took the consistent, endless work of several generations of activists to force Four Seas and its successor company to eventually turn over the site to Catholic Charities, which then worked with the Chinatown Community Development Center to get federal money to rebuild the hotel.

So while we commemorate the eviction, let’s not forget: This was a case of an overseas speculator, with no concern for the local community, aided and abetted by city officials including a mayor who is now a US senator, who could have stopped the tragedy and used the city’s leverage to buy the building and maintain it as tenant-run affordable housing — and who to my knowledge has never expressed a whit of regret.

That’s part of the historical record, too.

That's not very nice

Dianne Feinstein + you

Ha ha, asshole.

I don't understand how this happened. If we had somehow managed to saved the I-Hole, housing would be affordable for everyone. Maybe we should build a time machine so we can go back in time to prevent Dianne Feinstein from being born, and everything would be right in the world again.

If only we entrust the poor and immigrant populations to Jim Jones, it would have all ended up okay.

A $1.5m offer in '77 by Jim Jones was rejected. 55 rooms with 2 toilets and one shower per floor (3 floors). So that was about $30,000 per room back 40 yrs ago, when a house like Tims was going for maybe twice that. I dunno, maybe that was worth is – housing-wise. The tenants were paying something like $50/, but ya have to wonder if even triple that justified a $30k price tag. And just so ya know, $50/ for a rundown room in '77 was about market. We paid $100/room for an apt in Mission Dolores that year

Instead, after all those years, Catholic Charities (and the Feds) spent $28M to build 104 units for seniors, or about $275,000 per unit (in 2007). Cheap by today's standard; but considering what people pay for rent … ?