MUSIC Compared with the smooth operator currently installed in the Oval Office, how nervous Richard Nixon looks now as a representative of America abroad, all stiff grins, rumpled shiftiness, outbursts of awkward rhetoric. Reviewing vintage footage of him recently, I half expected a rappin’ granny to suddenly appear, and goofy Uncle Dick to start “breaking it down.” And yet, 40 years after California’s second-most problematic political progeny (pace, zombie Reagan) went to Beijing to “open China” — ending 25 years of separation and going on to win re-election in a landslide, despite the growing Watergate scandal — might it be time to look past the jerky, jowly image of Tricky Dick and reassess the character of the man and the moment, to keep us on our toes?

“Nixon was an incredibly complicated man, whose intellect constantly got in his way,” Canadian opera director Michael Cavanagh told me over the phone during a wide-ranging interview. “And it’s especially relevant to examine him now in that light, with a certain distance of history. We tend to stop at the jowls, the scandal, and the Republicanism. But it’s often been remarked during this election cycle that there’s no way in hell Nixon would ever be considered for the Republican ballot now. He was too small ‘r’ republican, too centrist. So there’s this complexity to him that confronts lefties with their own stereotypes, assuming most patrons of the arts lean left. That’s something I really like.”

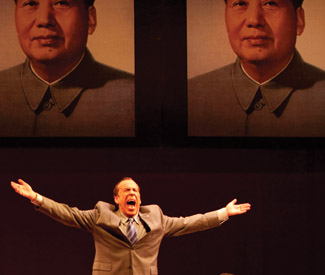

Cavanagh’s complexifying occasion will be his production of John Adams’ 1987 Nixon in China, part of the San Francisco Opera’s nifty-looking summer season. The opera, with a luminescent libretto by poet Alice Goodman and an engrossing, fever-dream score by Adams, whose melodies, time signatures, and musical reference points churn and shift like memory itself, takes us from the moment Nixon’s Spirit of ’76 touches down on the tarmac (Kissinger in tow), through his historic meetings with Chou En-Lai and Mao Tse-Tung, along with First Lady Pat on an eventful factory tour, and finally into the major characters’ bedrooms, memories, and fantasies. It’s a sensually intoxicating work, full of barnstorming arias sung by a multi-ethnic cast (you will have “I am the wife of Mao Tse-Tung” stuck in your head for days) that examines media spectacle, modern myth-making, and cultural difference on a truly, well, operatic scale.

San Francisco Bay Guardian Nixon was Californian, Adams is a longtime Bay Area resident. It’s the 40th anniversary of the China visit, and also an insanely contentious election year. The Bay Area as a huge Chinese population — many families escaped Mao’s Cultural Revolution. Do you feel any particular pressure bringing this production here, now?

Michael Cavanagh I feel a tremendous amount of responsibility, but I also feel a lot of freedom. Of course, the events the opera depicts and its roots in the Bay Area will resonate, and that’s hugely exciting. But this isn’t a documentary, it’s a rumination, more of a poem. As Nixon says in the beginning of the opera, “News has a kind of mystery” — and I feel that’s what Adams and Goodman were really expanding upon with this.

I do think that this production, especially, will bring up memories for a lot of people. I myself had an inkling of this whole thing happening when I was really young — it’s something that a lot of the world shares, a memory of this iconic moment, even if that memory is only a glimpse of pavement or a handshake, kind of like my own. The opera works with that abstraction, those fuzzy frames of memory that overlay images of the past, while still sharpening some of the more historically relevant moments. I hope people can relate to it on all of those levels.

SFBG Twenty-five years separate us from the opera’s premiere in Houston in 1987 — and yet China remains, to use a slightly loaded term, as inscrutable as ever to many Americans, yet as enmeshed in their daily lives as ever. What relevance do you think the opera may hold today?

MC I think it has an eerie relevance. Even back when Nixon in China premiered, China was still remote and threatening to many, and this was before the reform machine revved into life, before China’s emerging economic dominance. In one scene, in Mao’s library, Mao goes off quite poetically about the revolution, and how things were changing, and he plays fast and loose with the concepts of capitalism and communism, almost as if he foresees the necessary reforms ahead, that came to pass.

Beyond that, the opera is very prescient about the evolution of the media — this was one of the first major world events to be broadcast on a global scale, to be covered as the kind of spectacle we base much of our opinions and thoughts on today. We think of Nixon as shifty-eyed, but he was really just trying to figure out where the cameras were most of the time, trying to acclimate to this new kind of fishbowl environment in which political figures were treated like movie characters. The opera records the beginnings of all that, and ends with them reviewing their memories of everything that’s occurred as if it was all this footage, which it is quite actually on stage.

Basically, though, the deepest relevance a work can have is by connecting to the audience through its characters. Take Pat Nixon. We hurt for Pat Nixon. She’s been betrayed. Nixon promised her a simple home life, the comforts of family and a man at home, and here she is traveling all the way to China! She’s bewildered, but as First Lady there’s really no place for that, so she forges her own, I think very American kind of resolve that cracks a couple times, but still gets her through.

It’s a very poignant psychological and emotional study, projected on the world stage, and amplified as only opera can. That’s what opera does better than any other art form: it amplifies life.

SFBG You’re a Canadian — have you caught any flack for interpreting these events that are so associated with the US?

MC You know, despite appeals to the contrary, our two countries really share the same history. This version of the opera was premiered in Vancouver during the Olympic Festival — it’s what Canada chose to represent itself will to the entire world. And when it comes down to it, really, everything you do effects us Canadians just as much. We sleep with the elephant. *

NIXON IN CHINA

June 8-July 3, times and prices vary

War Memorial Opera House

301 Van Ness, SF.

(415) 861-4008