I’ve begun to regard Mark Twain as a fellow San Franciscan who anticipated our era’s Gilded Age long ago.

He arrived in the city by stagecoach, and praised life here in Roughing It by noting: “After the sage-brush and alkali deserts of Washoe [Nevada], San Francisco was Paradise to me.” He spent time in other parts of California, too, but Twain wrote about theatre and politics for the San Francisco Dramatic Chroniclefrom 1865-66.

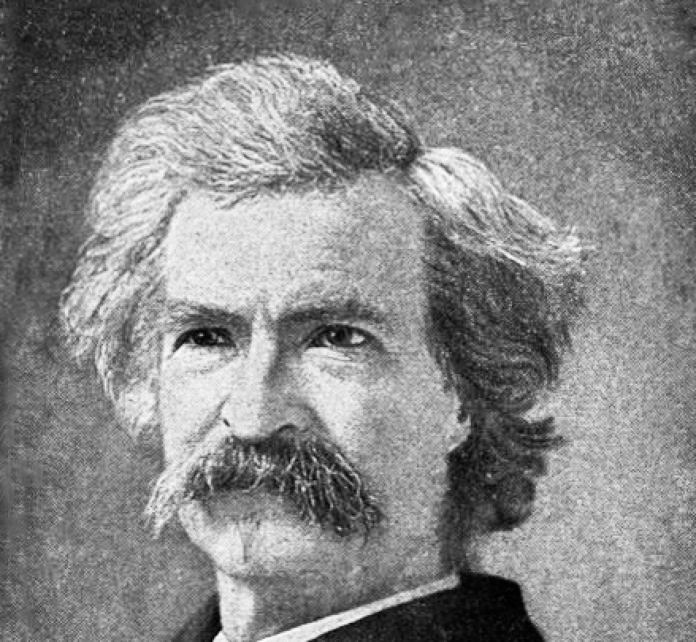

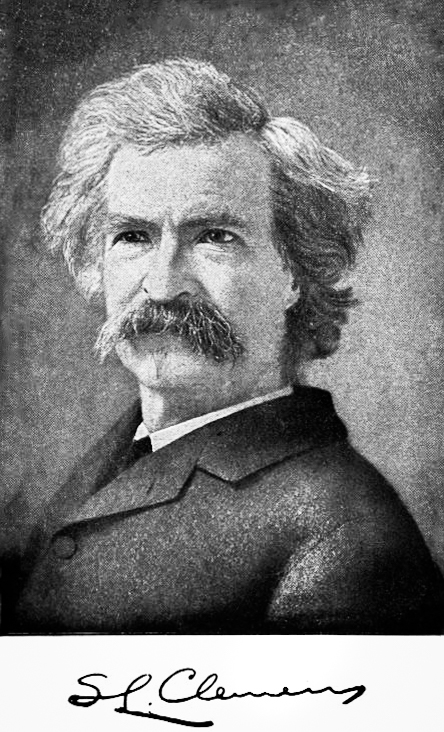

(That San Francisco publication was a forerunner of the Chronicle that still publishes here; Twain’s mostly unsigned contributions to it can be read in an online archive.) The writer, formerly known as Samuel Clemens, composed brief and often humorous reports on new plays and police corruption in San Francisco. Later in other locations he went on to write novels such as Huckleberry Finn, and some admirable speeches against imperialism, racism, and war.

I now find it necessary to defend my colleague, Mark, against the prospects that his life as a social critic, journalist and satirist will be defamed by Donald Trump or his new librarian of Congress. They are liable to contend that Twain promoted DEI (diversity, equity, inclusion) in some writings featuring a diverse group of Americans, and I can see Trump’s staff announcing that Twain and his supporters are no longer eligible for government humanities grants. (Twain himself never applied for such a grant, of course, but history and reality are sometimes neglected by the White House these days.)

Trump started to reinterpret (or should I say undermine?) the achievements of Twain in a July 4, 2020 speech he delivered in Nebraska, not far from Mount Rushmore, where some of the president’s supporters now want to see his face sculpted in stone. During that 2020 speech defending Confederate monuments and other “great” American culture, Trump noted:

“We are the culture that put up the Hoover Dam, laid down the highways, and sculpted the skyline of Manhattan. We are the people who dreamed a spectacular dream — it was called: Las Vegas, in the Nevada desert; who built up Miami from the Florida marsh; and who carved our heroes into the face of Mount Rushmore. … We gave the world the poetry of Walt Whitman, the stories of Mark Twain, the songs of Irving Berlin, the voice of Ella Fitzgerald, the style of Frank Sinatra, the comedy of Bob Hope, the power of the Saturn V rocket, the toughness of the Ford F-150, and the awesome might of the American aircraft carriers.”

Perhaps other Americans gave the world such writers (although America kept most of the rockets and the aircraft carriers for itself), but Trump and his censorial accomplices are now taking away access to culture, cutting and withdrawing government funds for education, the arts and cultural subsidies that allow universities, libraries, and their readers to find Twain—or his books and lectures about him, among others. (I won’t mention the other budget cuts which are far more damaging to the health and welfare of the nation; Twain by is no means the only victim here.)

The plural “we” in Trump’s claim to be a culture producer now seems a little too inclusive, since the president has started taking away more than he’s giving the public, except in tax breaks for the wealthy. San Francisco Bay area artists are among the losers of grants from NEA and NEH that are part of Trump’s massive takeback.

He could remedy the situation somewhat by restoring jobs and funds at educational and cultural centers across the country, or increasing them. He could pay for that and much more by redirecting some of the gargantuan military budget and increasing tax rates on the wealth of his family and his fellow billionaires.

In his 2020 Mount Rushmore speech, Trump claimed Twain was one of his American heroes. I could accept his speechwriter’s words more fully if the president had praised Twain’s comic critiques of bullies (as did Conan O’Brien when accepting the Mark Twain Prize for comedy at the Kennedy Center earlier this year), or cited the writer’s objections to empire, war, stock brokers and capitalism. I also would be happy to hear that Donald Trump recently read Twain’s first novel, The Gilded Age, which was co-authored with Charles Dudley Warner in 1873, since the book anticipates the political corruption of our own new gilded age. I would be pleased to hear the White House say that novel is still accurate in its description of corrupt Washington officials. Although Twain and Warner may have exaggerated for the sake of humor, some of what they said remains persuasive. For example:

“One of the first and most startling things you find out [in Washington] is that every individual you encounter in the City of Washington almost—and certainly every separate and distinct individual in the public employment, from the highest bureau chief, clear down to the maid who scrubs Department halls … represents Political Influence. Unless you can get the ear of a Senator, or a Congressman, or a Chief of a Bureau or Department, and persuade him to use his ‘influence’ in your behalf, you cannot get an employment of the most trivial nature in Washington. Mere merit, fitness and capability, are useless baggage to you without ‘influence.’”

I suspect this situation remains the same or worse in Trump’s Washington, where getting the “ear” of a senator or a president often requires a sizable campaign contribution. If your name is Elon Musk, you give a PAC $290 million to win the White House. If you run Qatar, you can give the president a $400 million “flying palace.” If you are Trump, you throw a $45 million presidential birthday parade, now scheduled to include tanks and other military might rolling down Pennsylvania Avenue with jets flying overhead and Trump saluting himself on June 14.

The situation would have provided Mark Twain with considerable material for a new short story (“The Celebrated Jumping President”) and given the White House new reasons to remove his name from its list of American heroes.

Twain was not entirely sanguine about life in San Francisco, either, where he wrote a number of articles about police corruption and unpleasant theatre for the Chronicle. Still, there are a street and a plaza named after him in our city, and you could say that “we” San Franciscans gave the world Mark Twain, or at least a newspaper for which he wrote.

He also gave the city and its residents some praise, although not without reservations. In 1864, after Twain visited the Hall of the San Francisco Board of Brokers, where stocks were bought and sold, he reported he was “agreeably disappointed in those brokers; I expected to see a set of villains with the signs of total depravity hung out all over them, but now I am satisfied there is some good in them, that they are not entirely and irredeemably bad.”

Although he clearly had some qualms about San Francisco’s money-changers, Twain concluded that St. Peter might even admit a few of the city’s brokers into Paradise. (Remember Twain once thought San Francisco was Paradise!) In the 1864 report on stock brokers, Twain’s St. Peter sounds a lot like Mark Twain himself when Peter tells newly deceased brokers: “I think you’ll find it sort of lonesome in heaven, for if my judgment is sound, you’ll not find a good many of your stripe in there!”

Joel Schechter is the author of several books on satire.