With a nearly singular focus, East Bay artist Lin Fischer has been recording the human figure for decades in acrylics on canvas. Describing her own work as expressionistic and brushy, she says that when someone recently referred to her work as raw, she agreed with the descriptor. But beyond mere technique, genre, or stylistic approach, the artist wants her work to communicate a kind of freedom.

“I want to convey a fresh new feeling of one being capable of making things work in life. That is what I have gotten from other artists whose work I love, and it has served me well. As a painter, that would be the greatest gift possible,” Fischer told 48hills.

A third generation Californian, Fischer (née Parsons) was born in Healdsburg and grew up in Sacramento in the 1950s, which she describes as being “a Mel’s Drive-In kind of place.” She currently resides in the Piedmont neighborhood of Oakland and works from a studio in West Berkeley. Fischer received her BFA in Painting from UC Davis in the 1960s and an MFA from Academy of Art University in San Francisco in1993. She began drawing the figure at an early age and says that nobody in her family had been an artist, so she was an anomaly.

“At first it was just something to do when I was bored, then it became a real interest. I was enamored with movie star magazines and all the photos of beautiful women and men, attracted to how they showed strength of personality and presence. My mother taught me how to sketch a stylized face for my first drawings in grammar school and it grew from there,” she said.

Even after all her years in the region, Fischer says she really enjoys not having to travel far to see really good art. A standout thrill for her was seeing a 2022 exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art of Joan Mitchell, whose early work she counts among her biggest influences. Nathan Oliveira and David Park, and other pioneers of the Bay Area Figurative Movement of the 1950s and ’60s, take up residence on that list as well.

“The art galleries are excellent here and the art community vibrant, with a lot of friends showing at different venues close by. It’s nice to go to an opening and discover ‘the usual suspects’ there,” she said, acknowledging a rich community of friends she’s made over the past 30 years.

Fischer says that early on in high school she was mostly drawn to the work of Modigliani and Picasso, then in college it was Matisse and Manet. She was aware of the Bay Area Figurative Movement painters but it wasn’t until the mid-1980s, when someone who bought a painting from her told her she was emulating their style, that she began really looking at them.

Though her focus on the human form has been mostly exclusive, Fischer sometimes veers off into painting landscapes as “a vacation from the figure.” On occasion, she melds the two in abstraction, as in her painting, The Other Path (2024). In two other works from 2024, Some Things Sometimes Bother Me and Laocoon Memory, Fischer says she uses background treatments to illustrate the emotions of the figure. Her medium is always acrylics on canvas, and she even goes so far as to call herself “wedded” to it, especially in trademark thick applications.

“I am ever-so-slightly addicted to the paint. I liked oils, but quit them for acrylics when I had babies in the 1980s because I was working in a bedroom in my house,” she said.

After 10 years in a studio in West Oakland, Fischer has been working in a smaller space in Berkeley since June, to which she says she is still adapting. The Oakland studio, though much larger, did not have windows that opened and was unusable for several months out of the year because it lacked heat and air conditioning. On a typical day in her current space, Fischer brings a concrete idea of what she is going to paint before she arrives there, seeing a work in her mind’s eye. But, she admits, that doesn’t mean she knows how it’s going to turn out. She says it just means that she is excited over an idea and the thrill of what she can do with it. Then when she actually begins painting, she surrenders the original thought altogether and allows the painting to emerge on its own.

“Sure, I am there, and it’s my hand and all, but there is clearly something else that takes over. I am so thankful for this something else. I have heard painters try to describe this before, but really the language is not adept at this kind of communication. I have been very grateful in my journey to be able to tap into this phenomenon. My reasoning about it is that I have just painted for so long now that I can let it happen in a way I could not fully for years,” Fischer said.

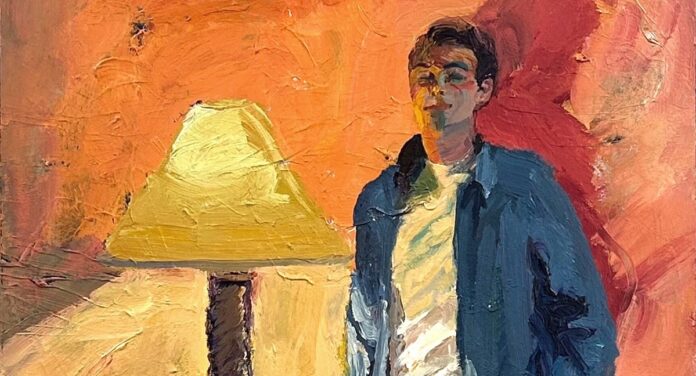

As an example of this, Fischer relates a story from the 1990s. She was working on a painting that her son modeled for titled, Young Man in Blue Jacket, and noticed she had bestowed upon him a mysterious smile that he didn’t actually have.

“I tried to take it out several times but I could not remove it. I didn’t understand it at all, but I decided I had to leave it in. I’m still surprised about it,” she said.

When queried regarding the arc and evolution of her work, Fischer dives right in, asking, “how many hours have we got?” Since the beginning of her career, she’s kept to two vital elements: preserving a certain amount of realism and welcoming feedback from a multitude of people along the way.

“One man I paid to advise me in the 1980s said I should wear a leather skirt and high heels (well, and a lot of other actually helpful things). It came as a surprise to him when I said I would never sleep with a gallery owner in order to get a show. I think about that now and then but have not changed my mind. The way I feel about myself is too important to my being able to do the paintings. Plus, I grew up Methodist. My paternal grandfather was a Methodist minister,” she said, connecting not just her ethics but also her creative vision to an innately spirituality.

As Fischer made her way in the art world in the late 1980s, a few galleries were helpful in giving her shows, for which she is grateful. A decade later, she visited both Wayne Thiebaud and Manuel Neri to show them her work. Both were “wonderfully generous” with their feedback, informing her practice going forward. She is embarrassed to add that at his opening at Berggruen Gallery around the same time, Thiebaud introduced her to some guests as “the best painter in the Bay Area.”

Into the early 2000s, thoroughly inspired by Joan Brown’s approach to painting the nude, Fischer painted a series titled The White Paintings, large nudes based on live models. The backgrounds were rendered in white paint, loosely applied over an initial color previously laid down on the canvas.

“Brown’s abstraction was beautiful. I was in awe looking at it. So inventive! So alive! Such thick paint, so much easy strength in the figure, almost not real, beautiful! I still love it,” Fischer gushed.

Later on, Fischer began a brief investigation into creating landscapes out of her imagination, spontaneously putting color down on canvas to see where it went. She says she always started with the horizon line, as a nod to Richard Diebenkorn (1922-1993), another artist of the Bay Area Figurative Movement.

“This was a wonderful journey of seeing where my hand would take me. I loosened up my stroke even more, and sometimes flung watery paint at the canvas in order to let it drip as it would,” Fischer said.

Upon seeing the David Park show at SFMOMA soon after, she got reenergized about painting the figure. She’d begin by painting the shadows on the figure and letting the rest be revealed to her.

“The light has always been key for me. At the drawing group I ran every Saturday for years, I always set up the lighting to project strong shadows onto the figure,” she said.

Fischer also introduced this technique in the classes that she taught for many years to private students and publicly at California College of the Arts, Walnut Creek Civic Arts Education, and master’s candidates at the Academy of Art.

Over such a long career, one experience that stands out to Fischer as being the highest acknowledgement of her work took place during a group figurative show in San Francisco curated by Theophilus Brown, which included her painting, Blue Thigh.

“A highly regarded gallerist, Charles Campbell, came to the opening. He walked in and, without seeing the rest of the show, stood in front of my painting without saying anything to anyone. He did not answer me or look at me when I went up to talk with him. He just stood there for a very long time, gazing reverently at my painting. Then he turned and left. That, to me, was the final assessment of the value of my paintings at the time, and still is,” Fischer said.

Fischer also mentions her intimate friendship with Oakland painter (and former curator at the Oakland Museum of California) Terry St. John, to whom she was introduced in the early 1990s. At one time, the two visited each other in the studio quite often as fans of each other’s work and shared influences. Also of note was a solo trip in 2021 to Paris and Giverny, one of her favorite places on earth and a trip she hopes to revisit in the future to explore plein-air painting.

“I feel very free when I am in Paris. Being surrounded by Monet’s water lily paintings in Musee de l’Orangerie was transformative. I teared up almost immediately and had to control myself. I painted water lilies on paper in the bathroom of my hotel room after a day visiting Monet’s house, pond, and gardens in Giverny. Back home, I worked on a series of large paintings of the Oakland Rose Garden near where I live in a commemorative recognition of my experience in France,” she said.

Fischer’s work has taken a few notable turns over more recent years. During the start of the pandemic, for example, she painted a series of figures against black backgrounds, something she had not done previously, saying it was her way to represent the unknown. Then later, a series of large paintings of men developed after an artist friend modeled for her.

“I had him take off his shirt which started a whole series of large paintings of men like this—only one is completely nude—that became important somehow. It was a sign of vulnerability which I felt was key to the work: a series of men with nothing to hide behind,” she said.

On the heels of that series, Fischer has returned to painting women, which she refers to as her old standby. She has been toying with the idea of doing a series of self-portraits, though she is not quite committed to the idea yet and has finished only a couple pieces as of this interview. One other alteration is that she has started working in a smaller format, an intimacy which she finds satisfying.

“Smaller is better for me right now, I think, as we are all a little timid about the future. I am feeling this. I want to include a landscape of abstract shapes behind the figure again, and a horizon line. I want to reassure people. And reassure myself,” Fischer said.

Fischer has shown her work in a variety of galleries, primarily in Northern California. Recent exhibits in 2024 include two group shows, Ascendance of the Figure in American Art at the Kim Eagles-Smith Gallery in Mill Valley and Among the Trees at Gray Loft Gallery in Oakland’s Jingletown neighborhood, in which she sold two paintings before the opening reception. Her work is included in the current group show Family Portraits at the Museum of Northern California Art (MONCA) in Chico that runs through May 11.

The extensive body of abstract figurative work by Lin Fischer, while clearly staying true to an original vision, will continue to temporally swivel and sway in subtle ways inside the distinctly recognizable rendering of the figure she has honed over decades of inquiry. Fischer says she hopes that the people who view her work come away with a feeling of renewal, a new excitement about what’s possible in life.

“Whatever you love, go get it. Life is, as it turns out, short,” she said. “The price of being afraid or too shy is way too high for us to pay. I am learning this myself, and I pass it on to you as an exciting possibility for the future.”

For more information, visit her website at LinFischer.com and on Instagram.