Recent developments in digital photography have made possible and absurdly easy what was once impossible and unthinkable: dozens of shots per second, shooting in near-darkness, and even video, captured before the shutter is actually pressed. Such superpowers may speed up a professional’s “work flow” (as if cameras were an assembly line), but what tech giveth, it also taketh away.

Pressing the button and letting the machine do the rest (as early Kodak ads boasted) reduces hard-won aesthetic achievement to choosing the best of hundreds of random “spray-and-pray” slices of the spatiotemporal pie. And artificial intelligence, with its slick rendering of imaginary scenarios created with verbal prompts, completely ignores the dedication, skill, and experience required for capturing the decisive moment with light and film.

There is a reaction against this automatization of vision, however. Younger photographers are choosing relatively low-tech older cameras that yield a recognizably “imperfect” filmic look, less sharply focused, and otherwise violating digital dogma. It reflects as well a desire to escape the relentlessness of online life. Photography, slowed down to a walk, restores the experience of observing reality, not glowing pixels.

The intimate, poetic photographs of Kayhan Jafar-Shaghaghi (who exhibits under his first name), an Iranian scholar with degrees in in history, business, and economics now living in Edinburgh, epitomize this rejection of the move-fast-and-shoot-things, FOMO-driven photographic ethos. Kayhan’s large-format still-lifes currently featured in his show Poise (runs through June 28 at Chung 24 Gallery) are made with an 8×10 view camera of the kind preferred by his idols Ansel Adams—whose work galvanized the young artist—and Irving Penn, whose work was featured in a 2024 solo exhibition at the de Young Museum.

Kayhan’s exquisitely rendered tone and color, both painterly and cinematic, suggest his roots in modernist photography, but their resonances go even further back into art history to the symbolic, allegorical still-life painting of the 17th century. The Dutch Masters rendered their still-life subjects immaculately, celebrating the brief, glorious beauty of flowers, but also propagating the then-dominant Christian faith in memento mori: visual sermons. We viewers are just passing through time, as are flowers and foodstuffs. The inner life that we discern in Jafar-Shaghaghi’s mysterious objects echoes our own subjective experience as sentient transients.

The gallery’s press release states, “Each image [in Poise] captures a state of suspended animation—a delicate tension before movement, transformation, or dissolution. Crafted through slow, intuitive methods, these photographs… bear witness to the uncertain equilibrium of our collective condition, speaking to the fragility and strength of that which endures.”

Kayhan’s fascination with the intricacies of film and paper, including his decade of experimentation with the extremely difficult process of printing black and white Cibachrome on IMAGO paper, testifies to his interest in history. We see this in his fidelity to the medium, with its aesthetic and technical strengths and weaknesses (by today’s standards) and his commitment to his subjects, household objects of scant intrinsic interest that gain force and presence from the artist’s vivifying focus.

“Poise” (2022), from which the show takes its name, suggests liminality or a threshold state combining both the opposites of balance and positional readiness. One of a series of works that also includes “Yield,” “Suspend” “Displace,” “Release,” and “Rest,” this image with its archaic, early-photography look assembles wooden blocks borrowed from a neighbor into various stacked configurations that suggest a human figure, simplified through Cubist eyes—an unmade work of art history interpolated into the present. Kayhan, by the way, favors the local, citing in a recent gallery interview the assemblage sculptor Joseph Cornell, whose rambles around his Utopia Parkway home in Queens yielded all the materials to populate his dream universe.

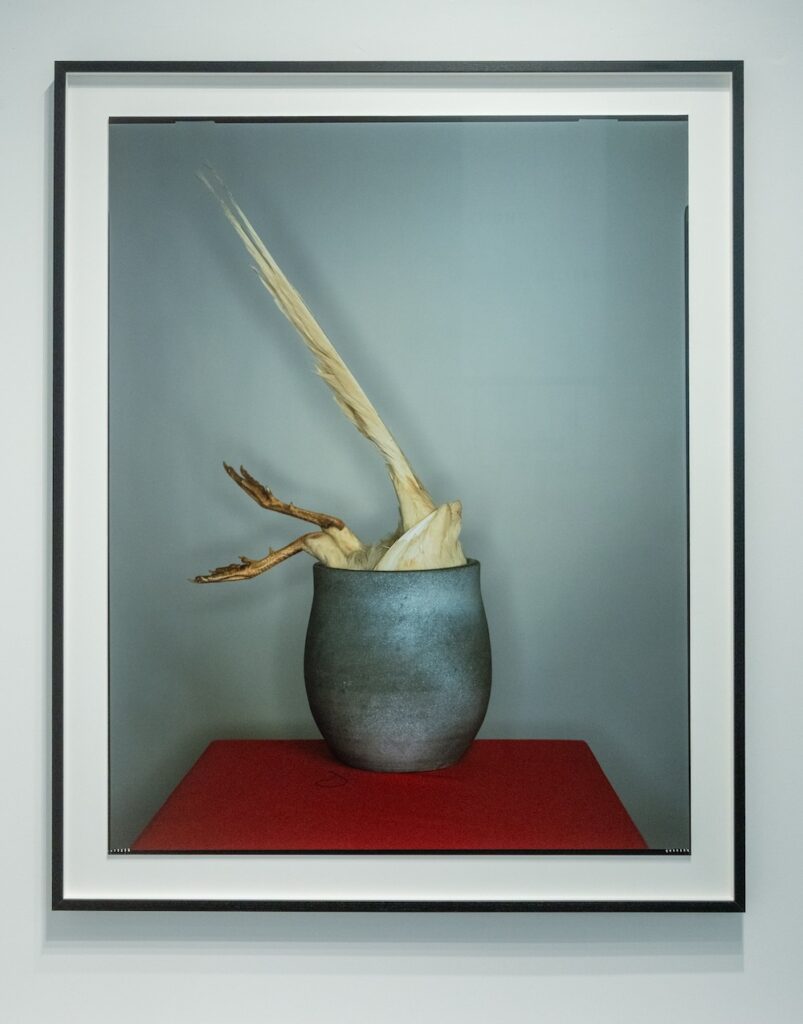

Speaking of dreams, Kayhan’s color print “Vessel” (2023) leans toward surrealism, with its depiction of a blue ceramic pot into which a bird, perhaps a chicken, appears to be burrowing, fleeing predators. But then again, perhaps it will end up as chicken-in-every-pot human fodder: soup is good food. Another color print, “Balance (2024),” presents a floral arrangement in which the red, yellow, pink, and white roses incline in all directions, suggesting both wilting and the daily heliotropic struggle for light and life. The most memorably strange work is “Adrift Also (Octopus on Plinth)” (2022) with its tentacled cephalopod protagonist, probably another neighborly borrowing (like the frozen snake in another one of his photos), decorously draped over a sculpture pedestal as if posing for its portrait.

Years ago, the art historian Suzi Gablik championed what she termed a “re-enchantment of art” from what she saw as meaningless formal experimentation (the aesthetic dogma of the day). Kayhan, whose cultural roots date from the ancient Persian art he saw in museums as a child, has a longer historical view than that which is prevalent in our algorithm-driven Anthropocene age. Kayhan: “I’m more of a scavenger… I respond to what I find. I try to be not that selective about whether I reject something or not.”

POISE runs through June 28. Chung 24 Gallery, SF. More info here.