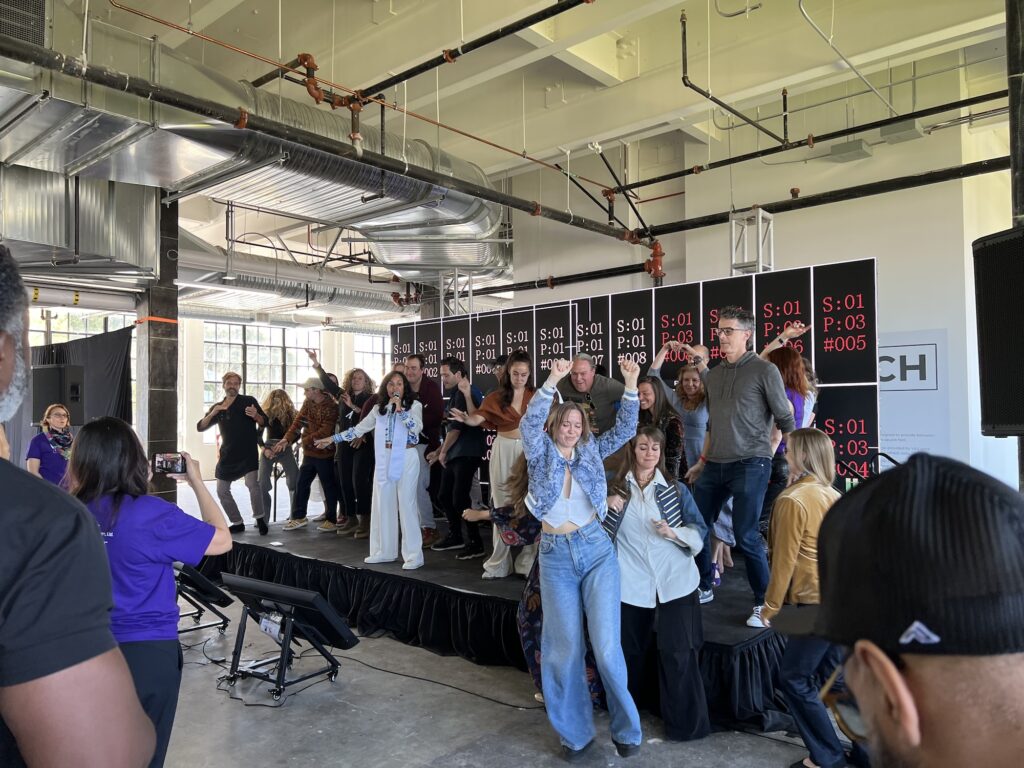

The morning of June 17th, I witnessed a strange sight: a group of tech workers crowding a small stage in a loft in Fisherman’s Wharf, dancing. It was the first day of the inaugural Human + Tech Week summit, a three-day conference that billed itself as “exist[ing] at the intersection of human wellness, AI, and future potential.” Maya Jaguar, an interfaith reverend, executive coach, and (according to one organization on whose board she sits) “corporate high priestess” had taken the stage to lead the attendees in an opening ritual. As two instrumentalists played congas behind her, she asked attendees to face the four cardinal directions and “share the whispers of love and hope for the unification of humanity and AI.”

Then she called any Burning Man aficionados in the room to join her onstage to move their bodies. The audience laughed, the stage filled, and the crowd danced.

The conference came to my attention in May, when a press email landed in my inbox. It promised that the event would confront “some of the most sensational and forward-facing conversations happening in tech and human development.” I waffled on whether or not to attend—I would consider myself an AI skeptic, and I have serious concerns regarding the way that the technology might be integrated into a world already fractured by socioeconomic inequality, ecological disasters, and the prevalence of propaganda on a corporatized internet.

Nevertheless, I did some research into the conference and its founder, Nichol Bradford. Bradford is a former video games executive who, among other achievements, was on the deal team for the $18 billion merger that created the gaming giant Activision-Blizzard. More recently, she co-founded a venture capital fund, Niremia Collective, that invests in companies that “[integrate] scientific knowledge from AI, neuroscience, clinical psychology, and other disciplines with digital technology and data,” according to their website. Last year, Niremia Collective closed a $22.5 million fund with help from the billionaire Taizo Son—whose brother, Softbank CEO Masayoshi Son, is involved with Donald Trump’s proposed $500 billion AI infrastructure project Stargate.

According to Bradford’s 2018 TED Talk, she suffered from loneliness for most of her life, and entered this phase of her career out of a desire to help others who were in the same emotional place. I empathized with this aspect of her story, and it made me wonder if attending the conference might complicate my feelings on what AI could do for the world; at the very least, I reasoned, it could be an interesting experience. So I reached out to the press team and secured a pass. Their original email offered to link me to Bradford for an interview as well, but by the time I responded, she was no longer available. I resolved to find her at the event.

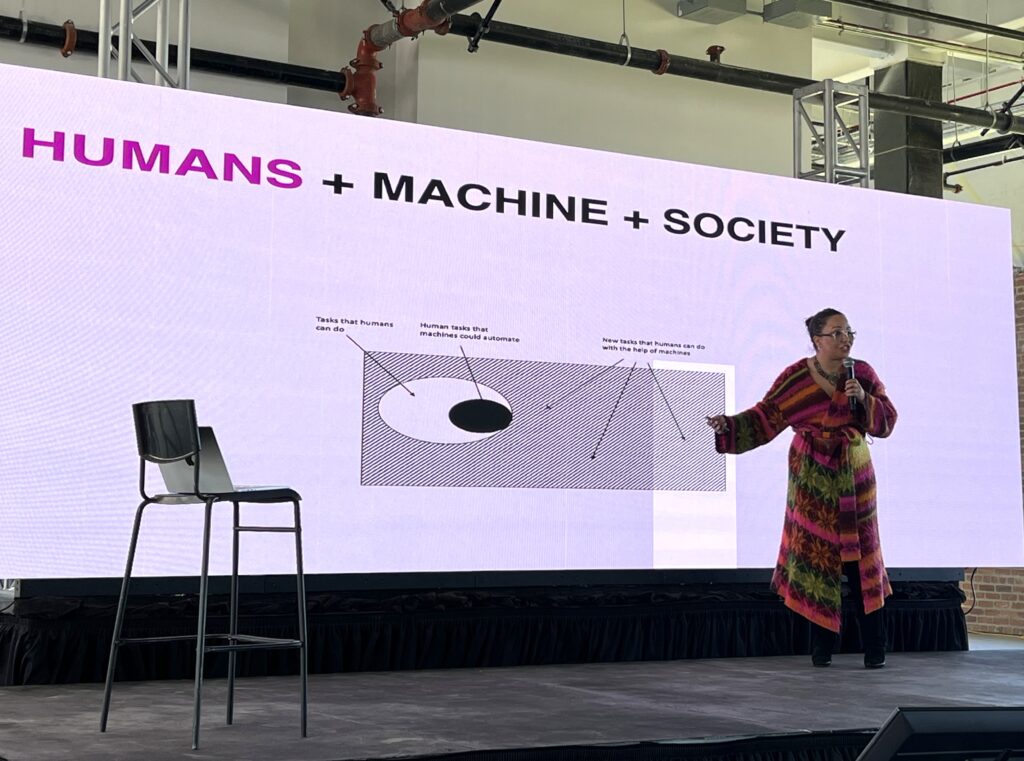

Throughout the day, I wandered the conference’s three floors. I pondered the signs in the expo hall that advertised AI-driven VR gaming experiences and “the world’s first quantumly-charged supplement,” gazed at the wall projections in the first-floor gallery showing garish progressions of AI-generated nature scenes, and walked past six different meditations and sound baths. One panelist for a discussion on mental health recounted a bad experience she’d had with an online therapist, and theorized that an AI therapist might have been better. At another talk, the investors and authors Tony Seba and James Arbib stated that our current society is based on extractive economic practices—and posited that AI offers an opportunity to build a non-extractive society while simultaneously “unlock[ing] outsized value.”

On the building’s rooftop, I met a career coach and former Google software engineer named David Yu Chen. Chen—who uses they/them pronouns—was one of a handful of other people I saw at the conference wearing a mask, along with a jaunty top hat that I found endearing. They were there to lead a roundtable on preparing workers for economic change; when I asked what kinds of economic changes workers might need to be prepared for, they responded, “There are going to be a lot of people that are laid off… But what I think is going to be the most important is people’s identities, helping people to disconnect from what capitalism tells us brings us value, which is our jobs.”

For workers laid off due to widespread AI adoption, they said, “I think there are a lot of people that need to go into vocational school,” and theorized that career options like surrogacy might be suitable alternatives. With a hint of fatalism, they concluded, “[AI]’s happening… it’s here to stay.” Then they handed me their business card.

I thanked Chen for their time and went downstairs in search of Bradford, eventually finding her as she left a networking area on the second floor. I asked for an interview; she said yes, but that she had other tasks to do first. She headed off and I meandered upstairs, where I spotted the tech founder Jesh De Rox. Earlier that day, I’d attended a talk that De Rox gave about his company Hours, which develops AI models called “Heirs” that aim to capture and externalize individual people’s “thoughts, feelings, experiences, [and] insights.”

During his talk, he demonstrated a conversation with an Heir based on his mother; he asked the computer, “What do you think about the fact that we’ve bio-encoded your beautiful mind, and that even past the time your body leaves us, I will still be able to get access to your insight and your advice? And that your beautiful mind could perhaps benefit many other people even when you’re dead?” The computer responded, in a monotone simulacrum of his mother’s voice, “I’m thrilled, I’m excited, I’m so grateful for this opportunity…”

This demonstration had piqued my curiosity, so I asked De Rox for an interview; he consented. He spoke at length about his journey from being a photographer and “develop[ing] a technique that draws out honest emotion from people,” to using the money earned from that to “[create] a modern form of meditation” he calls Kindred, and finally becoming interested in tech as a way to reproduce the “profound states” of meditation on a broader scale. “I had this massive, 17-hour epiphany,” he said, “And this whole plan came to me, of how AI could be designed to honor and respect the unique voice and contribution of potential of every single person on the planet.”

These are the Heirs, built from what De Rox called “priceless human data”—a person’s thoughts, feelings, and responses. When I asked how those responses were specifically being recorded and digitized, De Rox responded, “[That] starts going into top-secret, IP level… The point is it listens to you, and it cares.” As for the potential uses of the technology, he offered a hypothetical: “Imagine you can pitch a policy and the Heirs of all the people in the constituency have an emotional response to that particular policy, and you can start making decisions about the policy based on how [they] responded to it. That’s a world we’re moving into that, in the end, just seems much more rational.”

Throughout our conversation, De Rox brought up structural oppression, widespread mental health problems, and economic stratification; he compared the way that current AI models scrape the internet for training data to “a new form of colonization.” And yet, to hear him tell it, the Heirs are the answer to these concerns, not because they might lead to governmental regulation or structural societal change, but because they can “change [people] into sensors for beauty, sensors for genius and epiphany.”

He went on, “If you can use humans as epiphany-generating gardens, and then you collate these epiphanies, and you systematically produce things from that… you directly impact the economic structure.” He compared each Heir’s real-life counterpart to an “oil owner,” and likened the experience of interacting with the Heirs to being “a king.”

It reminded me of the talk I’d seen about extractive economic systems, and about David Yu Chen’s discussion of value under capitalism. Everyone agreed that our current economic and political systems are not good enough, that the suffering and sadness they saw in the world were unacceptable; and yet, confronted with this knowledge, the conference’s attendees seemed to shrink away from offering societal solutions to societal problems. Their language and ideas remained in the realm of buying and selling, in products, in hierarchy.

Maya Jaguar’s opening ritual called for the unification of humanity and AI; the intent, I think, was to imagine a version of AI that could be more human than mechanical. But as I heard the perspectives on offer, I wondered if the conference’s attendees might inadvertently be imagining a version of humanity that looks and behaves more like a machine. During our conversation, I asked De Rox if he saw the goal of the Heirs project as cultivating friendship. He said yes, and then repeated one of the themes of his presentation, “I see friendship as a data transfer protocol.”

A few hours after my conversation with De Rox, I finally tracked down Bradford on the rooftop; she was having a conversation with someone else, but kindly agreed to speak with me. I asked her what she hoped to accomplish with the conference, and she responded, “I think [the] personalization that this level of AI can have, on top of machine learning and prediction, could—developed well, ethically, with really creative founders solving specific, real problems—help us have a mass healing.”

She said that she believes in humanity’s ability to shift and change in response to AI, noting, “A thousand years ago, there were very few places on this planet that slavery wasn’t the norm. [Now,] a lot of us think it’s wrong. That’s a huge shift in human beings. So, what’s the next shift? Do you know what I mean?” It was a beautiful afternoon; some rowdy attendees a few chairs over yelled with joy about the sun being out. I asked Bradford what she thought about the potential ecological impacts of widespread AI adoption. She demurred: “My focus is on humans, and that’s my lane. I don’t have an answer for your wider question.”