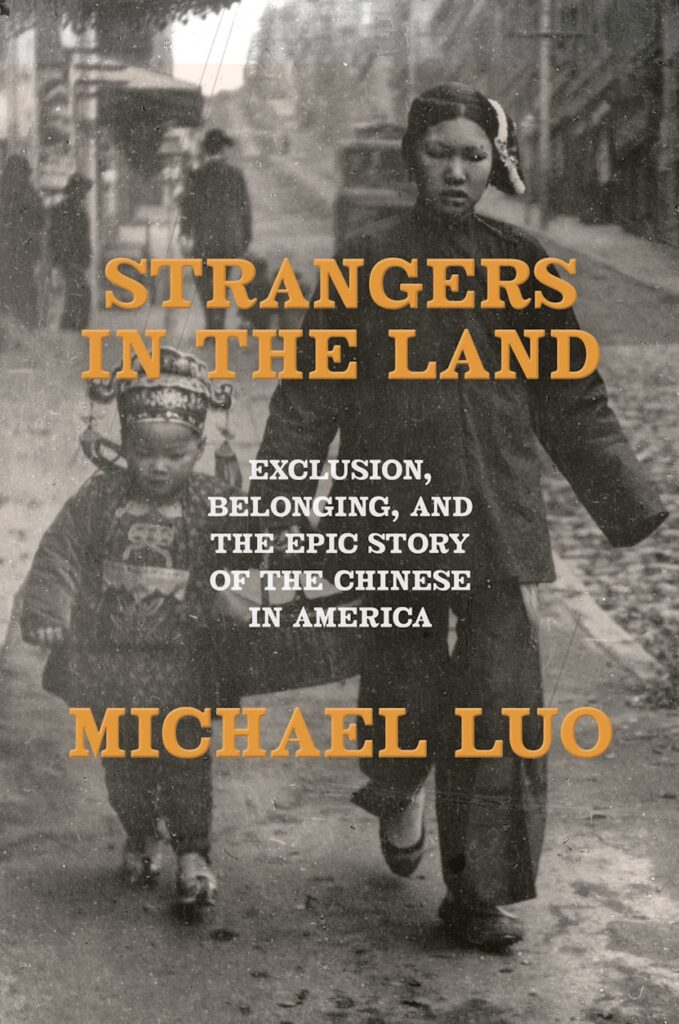

The epigraph for New Yorker reporter and editor Michael Luo’s first book, Strangers in the Land (Penguin Random House, $35) comes from Charles Yu’s novel, Interior Chinatown: “We keep falling out of the story, even though we’ve been here for 200 years.”

With his history of the Chinese in America from the Gold Rush to the 1960s, Luo is trying to write Chinese Americans back into the story—and to create, he jokes, the sort of history book you could give your dad for Father’s Day rather than yet another World War II tome.

The book covers the persistence and resistance of immigrants and citizens who faced racist legal and physical attacks, such as the Los Angeles Chinese Massacre of 1871, and a mob that burned down Chinatown in Rock Springs, Wyoming.

On Sat/20, Luo will be a virtual panelist for an Eastwind Books talk with writer Fae Myenne Ng and Norman Wong, a great-grandson of Wong Kim Ark, who fought a Supreme Court case to establish birthright citizenship. Luo talked to 48hills about his research, his quest to create memorable characters, and what his book has in common with KPop Demon Hunters.

48HILLS You are an investigative reporter, and you say that people in that profession are good at getting sources or they’re good with documents, and you are the latter. What do you think makes you good at that?

MICHAEL LUO I think it’s a certain relentlessness to get all the information. I mean, that’s the Robert Caro line, “turn every page.” He was an investigative reporter for Newsday, and documents were part of what he did as an investigative reporter. In my case, I’ve done a lot of reporting with data. I was kind of an early adopter of computer-assisted reporting, and I would do things like taking North Carolina’s concealed hands-on permit database and cross reference it with its criminal courts database, and look at how many people who have concealed handgun permits have committed gun related crimes. Stuff like that. That gives you a sense of my background as an investigative reporter. I was good at talking to people and interviewing people, but there is something about documents that is thrilling. It can’t spin you. Obviously, you have to sift and interpret. But I think, there’s a precision that can come from accumulating enough documents.

48HILLS You clearly did so much research to write this book. What were some of the archives and documents you looked at?

MICHAEL LUO One of the best repositories I went to and maybe one of the more surprising ones was the Presbyterian Historical Society of America in Philadelphia. These are the archives of the Presbyterian church. In the early days of the American West, the Presbyterian church sent missionaries to San Francisco to minister to the Chinese. One example is William Speer, who is a big character in the second chapter. He would have to write letters back home to the mission board every two weeks or two, and so you go to the archives, and there are these boxes and boxes and boxes of these letters. I went and photographed boxes of documents with a point-and-shoot camera and I then converted them into PDFs. Then I could just work with these documents for months. You would get these vivid descriptions of San Francisco and his encounters with Chinese figures. In the book, it talks about his interactions with some early leaders of the Chinese community who were kind of liaisons with Westerners, and his observations of them. In the second chapter it talks about this trial where some Chinese miners were killed by a white man, which eventually resulted in the California Supreme Court saying that Chinese testimony was inadmissible against white defendants. Speer was an interpreter at that murder trial, and so he has his direct recollections of it in those archives.

There are many, many other examples, like what happened in the Pacific Northwest in Tacoma and Seattle. One of the reasons I think there are such good archives is it was a federal territory, so they kept pretty good records. There was a lot that I got from the National Archives in Puget Sound and other parts in the Pacific Northwest. The University of Washington has incredible documents, and actually many of them they’ve started to put online.

That’s another part of the story. I signed the contract in the summer of 2021, and we were in the middle of the pandemic, right? So, I was working remotely. My kids were going to school remotely, and my wife was working remotely. We moved to San Francisco and rented a place for a little over a month. I was able to do my job remotely, and then in the afternoons, I would go to archives in the Bay Area because there’s so many important — at Berkeley, at the ethnic studies library, at the Bancroft Library, at the California Historical Society, and little historical societies in Truckee and Nevada City. They’re all in my acknowledgements. I also went down to the Huntington Library in Los Angeles, which has great archives. But the thing that was important from the pandemic is archives became very good at digitizing documents. It was extraordinarily important and useful.

48HILLS You have a lot of characters in your book. Could you talk about Gene Tong in Los Angeles and Ah Say in Rock Springs?

MICHAEL LUO In the chapter I wrote about the Los Angeles Chinese massacre, it was so important to me to say the names of the victims and to tell their stories as much as I could. Because of coroner’s reports and newspaper articles about the massacre, we do know the names of the victims, although they’re probably butchered since there was no consistent way to register Chinese names.

In each chapter, I really wanted a central character that the reader could form an attachment to. I aspired when I first set out to write this book, that maybe I’d be able to find a multi-generational family whose stories could kind of tell this larger story through them. When I pitched the book, the comparison I used was, “I want to do for Chinese immigration what Isabel Wilkerson did with The Great Migration [in The Warmth of Other Suns].” Isabel Wilkerson was able to interview, I think, around 900 people who remembered the Great Migration. I kind of quickly discovered that that finding a single family just wasn’t going to be doable as a single narrative spine, but I worked hard to make each chapter almost its own self-contained magazine story. It’s almost like an interconnected series of magazine stories and what I think comes through is the Chinese people become the central characters and you’re following their story through time.

For the Chinese massacre in Los Angeles, Gene Tong was the central character. He spoke English, and interacted with Westerners. To bring him to life, I had to assemble these little details just gleaned from scraps of a newspaper article, a classified ad, a memoir recollection. The detail that I love is that we know that he had a wife, and a roommate, and we also know that he had this poodle that lived with him. After the massacre, a newspaper reporter went through his destroyed apartment, which was filled with detritus, and was just a horror scene, and there was a poodle with a broken leg found whimpering in that destroyed room. I think it humanizes him.

Then Ah Say is more well known because he was kind of the leader of the Chinese community in Wyoming territory. It was a matter of assembling this portrait of him, and following his story through, from the beginning of the formation of the Chinese community in Rock Springs, through the horrible events of the massacre to what happened to the Chinese community in Rock Springs afterwards, when they returned to Rock Springs, and remained in Rock Springs for years afterward, and continued to experience hostility and racism and violence. His story of being a guardian of this community helps tell the story of this community, not just through that massacre, but afterwards.

48HILLS You have talked about how in 2016 a woman on the street told you to go back to China, and you followed her to talk to her, and she said, “Go back to your f-ing country.” (You always says “f-ing” when you talk about it.) You wrote an open letter to her at the New York Times, where you worked then, and it went viral. Why do you think that was?

MICHAEL LUO When the New York Times published this open letter to this woman, lots of people were reading it and sharing it, and then the Times decided the following day to publish it on the front page of the print newspaper, which is an extraordinary decision, both because of the subject matter and to the format, because it was deliberately digital kind of type of piece. A big statement. Then the other thing the Times did that was a big deal was they asked other Asian Americans who had experienced this type of thing to record their own stories. The video team quickly pulled together this extraordinary video where other Asian Americans shared their stories, and that went viral, until it kind of became this weeklong conversation.

I think it went viral because of this feeling of invisibility. I think that many Asian Americans feel both this lack of acknowledgement and this hunger for acknowledgement.

That’s what I’ve gotten glimpses of in talking about the book. The audiences that I’ve addressed for the book tour and book events are in some cases, heavily Asian American audiences, and in other cases, completely not. The book launch took place at the Museum of Chinese in America in New York with a heavily Asian American audience. Min Jin Lee, the novelist, was the moderator. The energy in the room comes from that kind of hunger for Asian American stories to be told. When I set out to write this book, I thought that it had the potential to be not just a book, but a cause.

48HILLS You say you wrote each chapter as a sort of magazine story. Were you playing around with different ideas?

MICHAEL LUO The interesting thing to me is when I look at this history, I also see a traditional narrative arc. If you think of the Chinese people as the central protagonist of the story, the kind of stereotypical three-act structure of a protagonist who confronts a series of complications, and there’s kind of a rising tension, and then suddenly, there’s this kind of climactic sort of moment, like a resolution and kind of falling tension as the protagonist reaches some sort of conclusion. This is what screenwriters often think about. I was just watching KPop Demon Hunters with my 11 year old, and I definitely saw the three-act structure in KPop Demon Hunters There’s a point kind of towards the end where my 11 year old turned to me, and was like, “Ought-oh, this is bad.” And then I said, “Don’t worry. We’re at that climactic moment, and there’s going to be a good resolution.”

MICHAEL LUO in conversation with Fae Myenne Ng and Norman Wong. Sat/20. Eastwind Books, Berkeley. More info here.