Last Tuesday, my friend Alice the Anarchist received an urgent communiqué from the Bertha Morisot Brigade of the Guerrilla Girls—not to be confused with the 19th century French impressionist painter Berthe Morisot, although it’s named after her.

“The Brigade last surfaced in the art world about 40 years ago, then went underground,” said Alice, “and suddenly this week, they contacted me!”

Alice shared their communiqué with me at San Francisco’s Legion of Honor, where paintings by Morisot and her friend Edouard Manet are currently on display in Manet & Morisot (runs through March 1). As we entered the exhibit hall, Alice explained that Berthe Morisot’s paintings are “currently half the focus of the exhibit here, and share the hall with 19th century painter Manet’s canvases. The Brigade named after Morisot is a late 20th century creation affiliated with the Guerrilla Girls.”

I had heard of the Guerrilla Girls previously; in fact, I once wrote about their satires of white male privilege in the art world, and how their well-designed posters pasted on the walls of prominent art galleries and museums ridiculed museum discrimination against artists who were women and people of color.

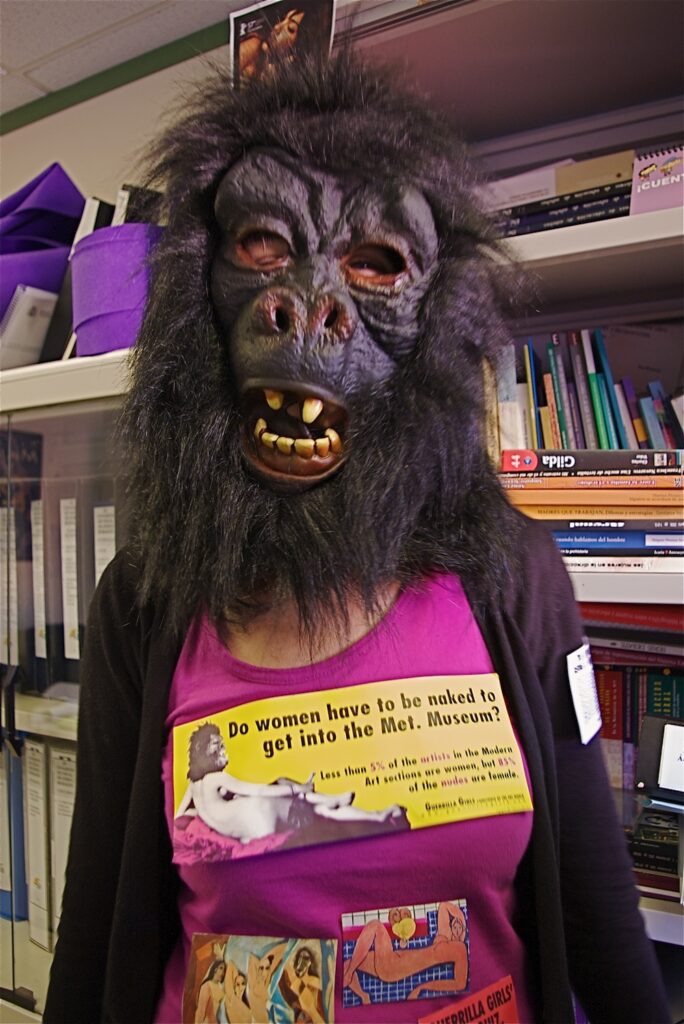

The GGs are women painters, sculptors, photographers, maybe even an art critic or two, who keep their identities secret. In the past, some of them wore gorilla masks in public to speak about their guerrilla campaign against curator and gallery owner biases. For decades they’ve called on museums and art galleries to show work by a more diverse group of artists. Guerrilla Girls’ groups sometimes name themselves after well-known artists such as Frida Kahlo and Berthe Morisot. Some of the GGs are probably well-known themselves; but they keep their own names out of it, their faces masked in public. They communicate mostly through wry protest statements and posters suitable for pasting on walls.

Inside the Legion of Honor, surrounded by paintings of French women in gardens, salons, and boudoirs, Alice herself attracted some stares from art lovers. The tattoos on her arms were works of art, ornate and tiny engravings.

“This arm features a flag flying over the Paris Commune of 1871,” Alice told a curious bystander, “you’d need a magnifying glass to see all the fine details. If you look closely, you can see the painter Gustav Courbet organizing other Commune artists above my elbow.”

The bystander declined her offer of the glass, but I accepted, and marveled at the miniature revolution.

“Morisot and Manet are two of the artists on this arm,” said my tour guide, Alice, “they were both living in Paris before the Communards took control of the city and set up a revolutionary government with universal suffrage, calls for a 10-hour work day (a reduction in hours at that time), and a demand for cancellation of workers’ debts.”

“You won’t find these pictures in the Legion of Honor’s exhibit,” I guessed.

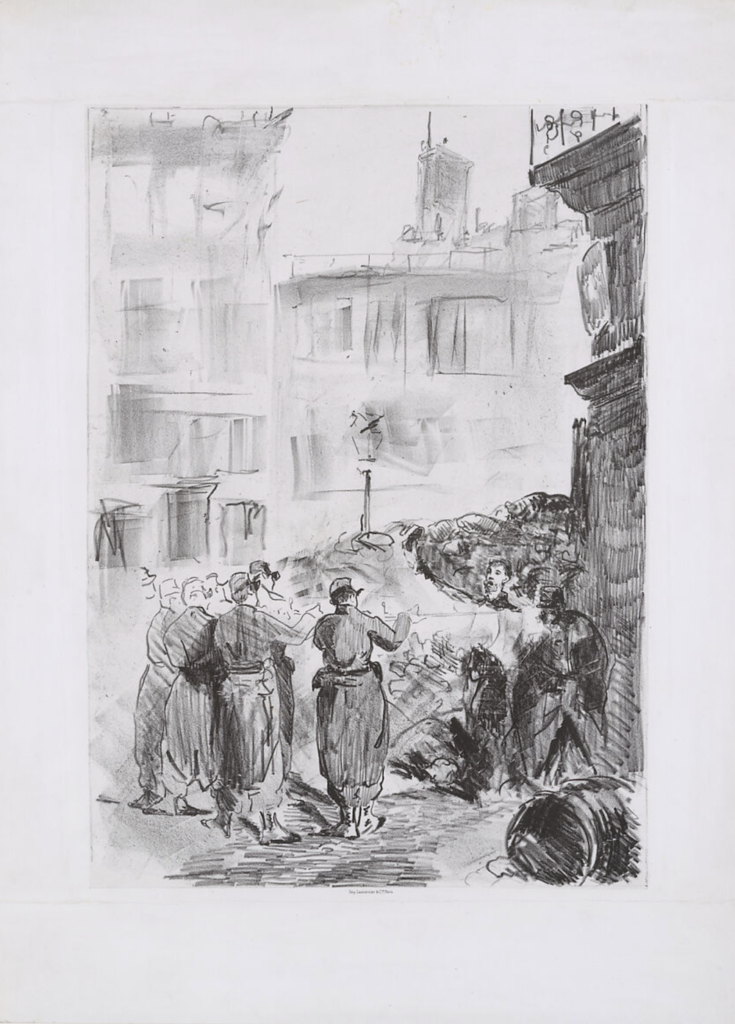

“No reference at all to the Commune,” Alice lamented, ”although the exhibit covers the same period. Look around, you won’t see any of the engravings Manet created in response to the Commune’s rise and fall, his depiction of “The Barricade” for example.”

She showed me a copy of Manet’s lithograph (on paper, not on her arm).

“The Berthe Morisot Brigade sent me this,” Alice acknowledged as I looked at the black-and-white depiction of a Paris barricade, “one of Manet’s responses to the defense and the destruction of the Commune. You won’t see this or its like on the Legion’s walls. They only show pastoral scenes.”

Alice then read from the Brigade’s communiqué: “While we applaud the recognition of Comrade Morisot’s innovative artistry, her pioneering impressionism now shown in San Francisco, we have to ask why no reference is made to the Commune, or Morisot’s flight from the conflict in Paris, toward the 1871 Commune. There’s also no discussion posted about Manet’s most controversial painting, Dejeuner sur l‘herbe (Luncheon on the Grass).”

“Well, the curators couldn’t cover every significant event of the era,” I said, in their defense.

“I suppose that’s why the Morisot Brigade contacted me,” Alice said, “to help the curators out, add a little more background and history to their wall captions. The Brigade wonders why the exhibit captions can’t ‘speak about the Commune and introduce the scandals that Manet set off in the 1860s with his paintings of nude women in “Olimpia” and ”Luncheon on the Grass.”‘ Why not note that Marisot was daring enough to associate with the man who painted these controversial canvases?’”

Alice continued reading the communiqué: “While another division of the Guerrilla Girls has asked if you have to be a nude woman to get into a museum—or onto one of its walls—the Morisot Brigade of the Guerrilla Girls wants it known that even if Berthe was fully dressed when she associated with Manet and when she posed for his portraits of her, that doesn’t make her entirely bourgeois and respectable. She was an outlier in her time, for which we commend her, even if she and Manet did not take arms and defend the Commune.”

Alice was confident that we hadn’t heard the last of the Brigade. “They’ll be back. That doesn’t preclude,” she predicted, “reinforcement from a newer Guerrilla Girls contingent, such as the Cindy Sherman Clique (honoring the accomplished experimental photographer) introducing new protests.” Currently the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C., is showing a retrospective celebrating 40 years of work by the Guerrilla Girls, and the Getty in Los Angeles features an exhibit titled How to Be a Guerrilla Girl.

Meanwhile, Alice wishes that the Legion of Honor will enlarge its Manet and Morisot exhibit a little and display the Brigade’s illustrated communiqué, including its references to the anarchist Courbet and the 1871 Commune. She would even give them a framable copy of her tattoos.