“Ideals without common sense can ruin this town … What does that get us? A discontented, lazy rabble …all because a few starry-eyed dreamers …stir them up and fill their heads with a lot of impossible ideas!”

—Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore) in Frank Capra’s “It’s A Wonderful Life,” 1946

In Frank Capra’s “It A Wonderful Life,” for the super-rich banker, Mr. Potter, the town of Bedford Falls was poised on ruin because of the non-sensible lending policies of the town’s saving and loan, which continually made home loans to working people that built a community that sustained the town. A misplaced deposit leads the saving and loan to insolvency, causing its beleaguered manager, Jimmy Stewart, to wish he were dead. An angel is empowered to make the wish seem to come true, to show Stewart how his loss would affect others.

To illustrate what life would have been in Bedford Falls without him, the angel sends him to the Bedford Falls that never had him, now named “Potterville.” Potterville’s main shopping street was lined with bars and night-time entertainment venues of various types, not the retail shops selling goods to locals that was Bedford Falls main street. Stewart comes to his senses and the angel switches the town back to Bedford Falls, where the community pours donations to the saving and loan, which saves it from ruin.

Mayor Lurie’s re-zoning plan, now set for Planning Commission approval September 11, has all the sensibility of a “Potterville” transformation of San Francisco: a rabid disdain for the “starry-eyed dreamers” of San Francisco who currently live in the city’s neighborhoods (“othered” as Nimbys), and a deep kiss on the lips of the “common sense” real estate investors eager to displace the current “discontented rabble” with a whole new set of up-market highrise towers full, not only of upscale housing but also various new “commercial uses”—all planned from the top down, with local voices silenced, all benefiting folks not yet in San Francisco but sure to come (until they don’t).

The proposal, devised by the Breed administration and adopted and expanded under Lurie, is centered on western San Francisco, a portion of the city that has a high proportion of the Chinese population both as residents and merchants, and which currently provides the majority of both family and senior housing (and the overwhelming majority of “multi-generational” housing) in San Francisco, and which is currently underserved by public transit.

While billing itself as a “family housing program” that will expand density along major transit corridors it, in fact, does little to either preserve existing family housing or require the affordability necessary for actual families to live to in the new housing it proposes. It provides no impact fee on developers of the new dense housing to pay for public transit operations—at a time when public transit faces financial collapse.

There are six fatal flaws in the Lurie proposal that need to be understood and corrected if the plan is going to avoid displacing more families and neighborhood-serving small businesses.

1. Lurie’s rezoning proposal fails to meet the affordable housing San Francisco needs, as defined by his own administration.

The most salient failure of the Lurie proposal is it inability to lay out a plan that will meet the affordable housing needs defined by his own Planning Department. Moreover, the proposal includes a new policy that will convey publicly owned land of the SFMTA to market-rate developers with minimum affordable requirements, instead of limiting all surplus public land for 100 percent affordable housing development.

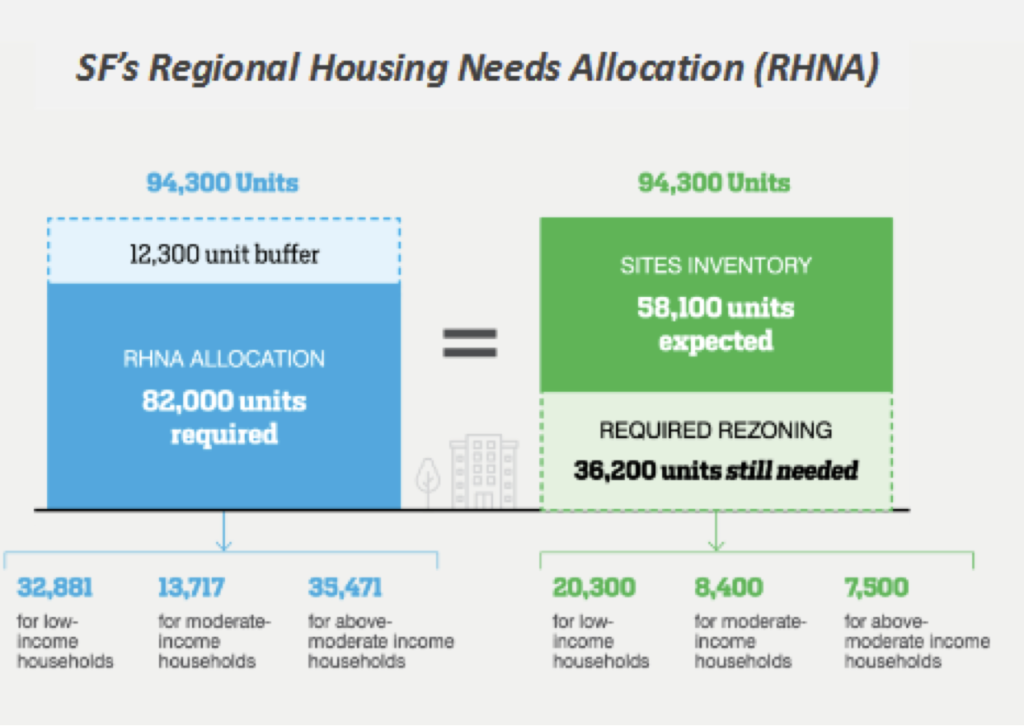

The handout supplied by the Planning Department on the Lurie proposal contains the following graphic:

Under state law, The Association of Bay Area Governments estimates the housing need for the next seven years for San Francisco, by income categories. It should be noted that Mayor Breed appointed, as San Francisco’s representative to the ABAG committee doing the calculations a Yimby founder who lives in the East Bay. With such help, it isn’t surprising that the 2023-2030 estimate reached the astounding number of 94,300 new units, an eye watering 326 percent increase over the previous 2015-2022 RHNA estimate of 28,869 units for San Francisco.

What had changed? Why the huge increase in a locality that has not seen a 300 percent increase in population (indeed, San Francisco’s population continues to decline) and had, at the time, some 70,000 housing units approved but not built in its “pipeline?”

State law had changed and given real estate speculators a vested interest in huge, un-achievable RHNA requirements. State Senator Wiener, the Yimby poster boy, had passed a state law saying that if a county failed to meet its RHNA goals then new housing proposed for that county would be approved “as a matter of right—that is, automatically, without public hearing or review by local planners.

Wiener’s legislation did not require that these projects be built, but did create a new financial instrument—an approved building permit that could be sold and re-sold in one of the hottest real estate markets in the world. And as the saying goes, “that ain’t nothing” if you’re a real estate speculator.

But speculating in approved projects does not produce housing, especially critically needed affordable housing.

As of Sept. 1, the current pipeline of approved but un-built housing units numbers 71,772, with some 17,378 being classified as affordable, or 24 percent, according to the Planning Department’s data.

This fact undermines a key Yimby/Lurie rationale for the rezoning plan: That existing density and approval processes stop the city from approving critically needed housing. If 71,000 units have been approved but are un-built by developers, something else is happening—not dependent on either zoning or approvals. What that might be and proposals to correct it are not a part of the Lurie plan.

Returning to the above graphic, the Lurie rezoning program does take into account the huge pipeline of approved but un-built housing by reducing the RHNA requirement by some 58,100 “units expected”—without a specific mention of the pipeline or why only 58,000 and not the full 71,000 units are “expected.” What happened to the remaining 13,000 units has never been explained.

But what is significant is that the graphic lists 28,700 of the remaining 36,200 “units still needed” by “required rezoning” earmarked for low- and moderate-income households. That’s a whopping 79 percent of the total units needed. But as the pipeline figure show only 29 percent of the expected units, some approved a decade or more ago, are affordable— showing the real capacity of the city to produce affordable housing.

With such a high affordability bar set by the Planning Department, the Lurie re-zoning proposals must contain a historically aggressive policies to achieve that goal. They don’t, not even close.

There are two programs aimed at affordable housing in the Lurie proposal: The Housing Choice Housing Sustainability District (Sec.344) and the newly proposed Non Contiguous SFMTA Site Special Use District (Sec.249.11). The first sets the affordability goal at 10 percent “affordable to very-low or low-income households” and the second sets the goal at between 22 percent and 24 percent, depending if they are rental or ownership units.

The SFMTA proposal is especially odious because it gives to the SFMTA Commission (appointed totally by the major) the ability to recommend waving both the Transportation Sustainability Fee and the Jobs-Housing Linkage Fee to the Board of Supervisors. Project built on SFMTA sites could be as high as 400 feet. These publicly owned sites would then be overwhelmingly market-rate housing and commercial buildings, not quite the comfy “family housing” hawked by Lurie.

The one certain affordable housing program that could be adopted at the local level is the dedication of surplus public land for the exclusive use of affordable housing. Site acquisition is 50 percent of the cost of affordable housing development, a cost totally able to be met by restricting the use of public land for affordable housing.

Instead, Lurie is proposing to allow massive market rate development on some of the largest parcels in public ownership—Muni’s Presidio and Kirkland yards alone could accommodate several hundred units of affordable family housing, serving thousands of San Franciscans for 50 years or more.

But the bottom line is that the Lurie re-zoning would not come close to meeting the RHNA goals of affordability. It seems that somehow the state has indicated to Lurie that it would be just fine to miss the affordability requirement—as long as the market-rate and commercial projects go forward.

2. Lurie’s rezoning may destroy more existing affordable family housing than it will create, especially housing that includes multi-generations in single households as much of the Sunset and Richmond does.

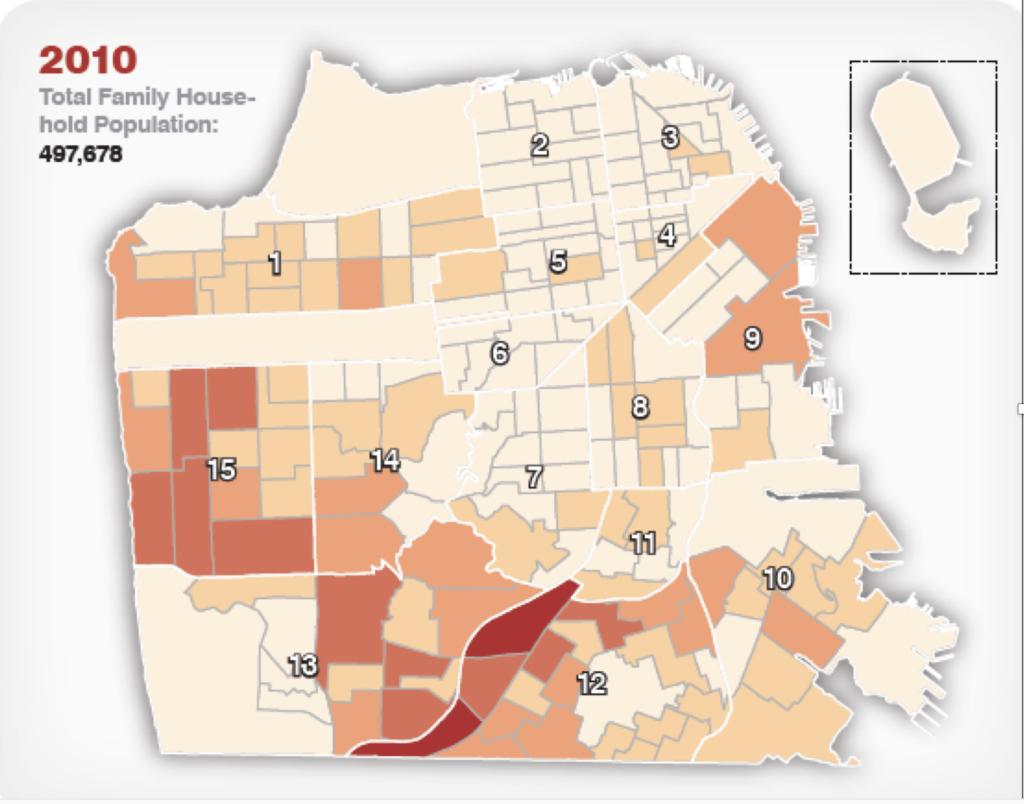

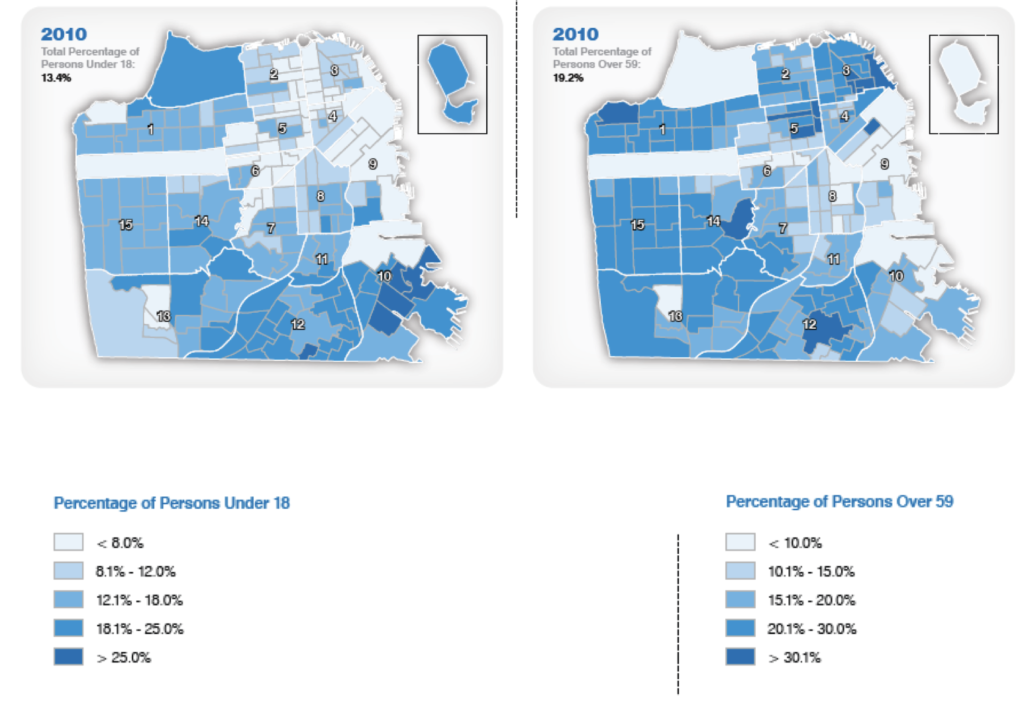

The Richmond and Sunset contain a huge amount of the city’s family housing, especially housing for both children and seniors.

Three maps from the Department of City Planning GIS page (https://sfplanninggis.org/intro/) show the story graphically:

The Richmond and Sunset have large populations of children AND seniors—which is not true in most areas of the city, which either have a high proportion of children and few seniors (Presidio, Bayview) or large senior population and fewer children (North Beach, Nob Hill).

This “multi-generational” character of the Richmond and Sunset reflects the fact that the area has a high concentration of Asian households, which often include grandparents, parents and children all living in the same household. This is reflected in the fact that of the 12 census tracts with the largest number of family households, 50 percent of them are in the area covered by the Lurie rezoning (as shown in the map above).

For Lurie and his Planning Department, it seems that only nuclear families count. Lurie’s plan allows the demolition of existing housing (even rent controlled homes) if the new housing equals or exceeds two-bedroom units of the existing buildings.

But where the Lurie rezoning goes totally off the rails as a “family housing rezoning” effort is allowing the conversion of a housing use to a commercial use in all 37 neighborhood shopping districts covered by the proposal.

In more than half of these districts, the conversion of a housing use above the first floor (or sometimes the second floor) is simply prohibited. Under Lurie’s plan, any existing housing use above the first floor can be converted to a commercial use by the vote of the four Planning Commission members the mayor appoints.

The language of the proposal allows the conversion of not only existing housing uses but also the new housing built under the plan. It’s impossible to determine the net effect of these dramatic changes will have on the total housing produced under Lurie’s plan. The plan maximizes profit for real estate speculators, and does not guarantee new housing for families at prices they can afford.

3. It will displace small, locally owned neighborhood-serving businesses and provide no meaningful means of retaining them.

The Lurie rezoning is centered on 37 shopping districts, which currently house some 4,300 registered businesses, according to the Planning Department. The plan itself states: “Increased residential development could result in displacement of existing businesses.” But it offers no concrete policies to keep such displacement from happening.

In a presentation made before the Small Business Commission in late July, the Planning Department claimed that 915 businesses were located on parcels where Lurie’s proposal would remove “development constraints” and another 207 businesses were “located on suitable parcels” for new development, meaning 1,122 of the 4,300 (26 percent) businesses in the rezoning area are facing displacement.

The overwhelming majority of these businesses are neighborhood serving retail businesses and hundreds are owned by women and people of color, with most employing San Francisco residents. The Planning Department offered no specific strategy to keep these businesses in place, and no specific policies within the zoning proposal itself to avoid the displacement. The Lurie rezoning has no polices that preserve existing neighborhood-serving or legacy businesses in place; the only policies are aimed at relocation.

After planning staff read off a list of existing city services aimed at assisting small businesses, most of which are already oversubscribed, Miriam Zouzounis, vice president of the Small Business Commission, dismissed them as having no real impact on the new threat contained in the Lurie proposal. “I don’t trust the city,” she said.

4. It provides no new revenue for public transit and no means to support current service levels.

The Lurie proposal removes most parking requirements in new development, but it contains no new transit impact fees on the new development, assuming the existing Muni system can absorb the new ridership. As shown above it even potentially waves the existing Transportation Sustainability Fee on large projects allowed in the proposed SFMTA SUD—a particularity ironic policy given the financial cliff facing Muni. The greatest density in the mayor’s proposal is along “transit corridors.”

All of this is being proposed in the context of a $322 million Muni deficit. Add to that a recognition that both regional and local transit funding ballot measures, even if passed, will not fill that hole. While proposing a steep increase in population along transit corridors, the rezoning plan simply ignores the funding crisis facing the transit system.

Instead, Lurie seems to prefer Waymo, Lyft, and Uber as his recent approval of them returning to Market Street shows. Waymo has dramatically increased its fleet while Muni continues to reduce the number and frequency of its buses. Even in San Francisco sometime one and one equal two: If there is little or no new revenue for Muni, service will continue to decline and the basis for a “transit oriented” dense housing proposal will simply disappear.

Calling a Waymo to get the kids to and from school sounds like a hell of a plan for all the families Lurie seeks to build housing for along transit corridors that no longer have public transit.

In June, the mayor cut service to two lines that serve western San Francisco—yet his rezoning plan continues to claim it is “transit oriented” and calls for more density in the western neighborhood in a style that is simply Trumpian in its denial of reality.

5. The Lurie proposal allows endless speculation with approved projects and no hard requirement to actually build the housing.

How can it be that San Francisco has 71,000 approved units that have not been built in an endlessly declared “housing crisis?” The answer is simple: the willingness to accept speculation in approved housings projects.

Treasure Island (6,500 approved units) and Parkmerced (5,314 approved units) have been stalled for two decades as one ownership group sells its equity in the project to another speculator. The same is true with the development at Bayview Hunters Point Shipyard (9,637 approved units) and the Potrero Power Plant (2,228 approved units) Money can be made by not building approved projects.

Lurie, with this rezoning plan, seems not to care. The Yimbys seem not to care. Senator Wiener seems not to care. The State of California seems not to care. They all seem to care only about streamlining approvals of massive new projects—and they don’t care if those projects ever actually get built. Only the folks who need the housing care—but they have little or no voice in the matter.

Developers are under no city obligation to build the housing they get approved in a timely manner, if at all.

Only one of the several alternative proposals in Lurie’s rezoning plan has a mandatory “use it or lose it” requirement: The Housing Choice Housing Sustainability District. The proposal states that the approval of a project “shall expire” if the developer “has not procured a building permit within 30 months” of its planning approval. While 30 months may be overgenerous given our hair-on-fire housing crisis, at least it recognizes the problem.

Why this is not a requirement of all projects created in Lurie’s re-zoning plan?

Again, the answer is simple: speculation. After all, billionaires talk to other billionaires, and business is business. Which, of course, is why we have an affordable housing crisis not just in San Francisco, not just in California, not just in the USA, but world-wide.

6. It pits current San Franciscans against future San Franciscans.

The Lurie rezoning plan was devised by London Breed, perhaps the most divisive mayor since the “father of redevelopment,” Joe Alioto. Breed delighted in the practice of the politics of pitting one set of San Franciscans against another. In the end, it cost her the election, as voters grew weary of her constant scapegoating and blaming others for the failure of her policies.

Lurie won with a feel-good campaign centered on bringing us all together by following a middle road, through a set of moderate policies aimed at including us all in a better city. He added the astute pursuit of the Chinese vote, which had completely soured on Breed, making him, in effect, the second mayor of San Francisco elected largely with Chinese support (Willie Brown was the first).

It was odd that he would then accept a massive rezoning proposal that was itself based upon the most divisive of all possible policies: displacing existing residents, many of whom were Chinese residents of the Sunset and Richmond who had voted for him. At the very heart of the Breed rezoning proposal was a massive assault on current residents and businesses of western San Francisco, with policies and proposals that required the demolition and displacement of homes and businesses of current residents.

In polite San Francisco politics, one does not talk about race, as the civic assumption is that in liberal San Francisco racial politics is simply not practiced. Officially the city supports diversity, equity, and inclusion. Yet in land-use policies, the city has a rich and continuing history of rank racism, from the policies of “Black removal” of the Redevelopment Agency to the attempt to relocate the Chinese out of downtown to the deep and invisible reaches of the South for Market after the 1906 earthquake and fire.

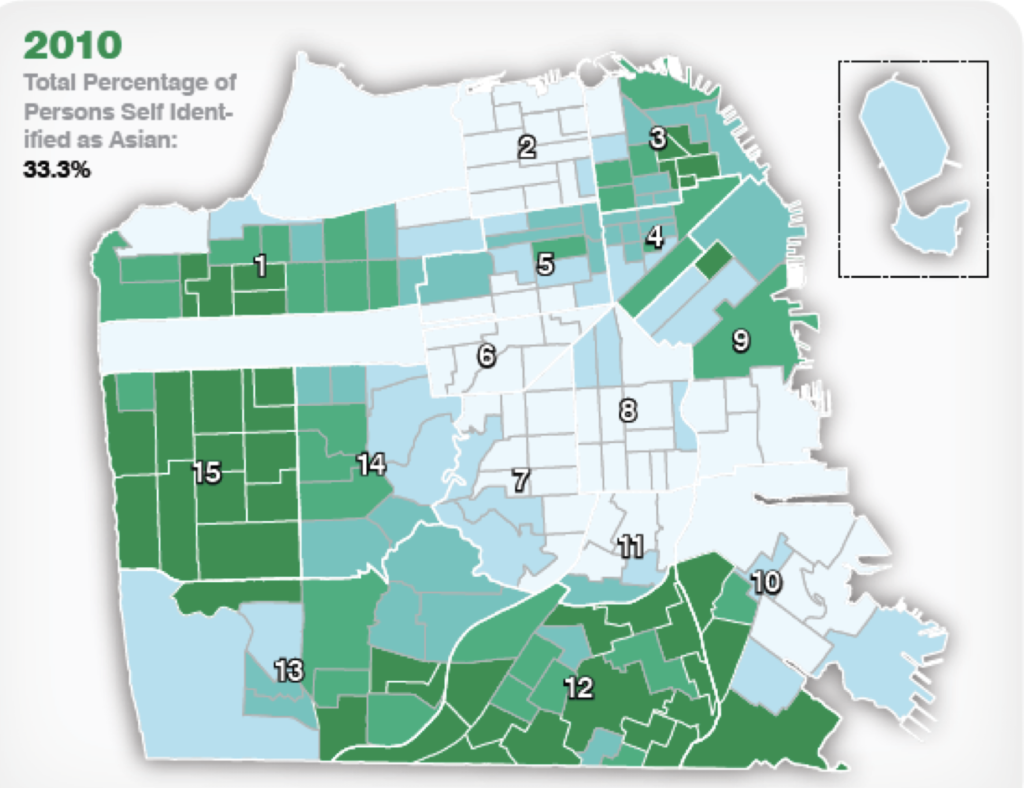

Using another map from the Planning Department GIS page this fact becomes clear.

At the very heart of Lurie’s proposal is the heavily Chinese Sunset and Richmond. How Lurie and his advisers failed to see the disproportionate impact a zoning proposal that allows unlimited demolition and conversion of existing housing would have on that specific population is baffling—unless, of course, they didn’t care.

San Francisco’s Chinese voters have become increasing important in citywide elections, as the number of Asians increased from 29 percent of the population in the 1990 Census to 37 percent in 2020. with approximately 60 percent of the Asian population Chinese. The Chinese vote is simply determinative in the Sunset and the Richmond.

There can be little doubt that Chinese residents of the Richmond and Sunset see the rezoning as a displacement threat to their community. Even the Chronicle has recognized that concern around the rezoning is a factor in the almost certain re-call of the District 4 supervisor (here and also here). Engardio is a strong supporter of the Yimby agenda (which included the closing of the Great Highway) and of Lurie’s rezoning, proving, as we will see if he is recalled, that the Yimbys in San Francisco can get you into more trouble than they can get you out of.

It not good policy and certainly not good politics to propose land-use policies which seek to replace current residents with more wealthy future ones—as Breed might well have told Lurie if they are still talking.

Lurie’s rezoning proposal will not result in more family housing and quite possibly reduce it through demolitions and conversions, and instead boost large-scale commercial uses deep into existing residential neighborhoods. It has little if any affordability, which is the main need of families, while handing over to market rate developers critically needed public land which could be used for 100 percent affordable housing development.

It will displace hundreds of small businesses, many of which employ local residents, with no plans to prohibit such displacement and no new initiatives to fund the relocation of those businesses. It will certainly worsen the city transit crisis by increasing density along “transit corridors” while providing no new funds for the additional riders and no operational support for the existing service.

It either purposely or ignorantly targets the largest multi-generational set of family households in the city for displacement in a manner that falls hardest on the Chinese community, which will harden attitudes and make the pursuit of common goals all the more difficult. And, astoundingly, it doesn’t require that any of the housing be built but instead allows the uncontrolled speculation of buying and selling, merging lots, and demolishing small buildings and displacing businesses and residents—while the great land use game is played for the benefit of the few and the misery of the many.

There is little prospect that either the Planning Commission or the new “moderate” Board of Supervisors will meaningfully amend the measure, so it will pass basically as written before the end of the year. Then the choice of our future is in our hands. There are two elections next year. A ballot measure amending Lurie’s give-away should be on one of them.