On Veterans Day 1950, a handful of gay men hiked up a hillside in Los Angeles, in a neighborhood then called Eden Dale. Meeting in secret was risky. Being discovered could mean arrest, entrapment, a lost job, or a beating.

Yet these men—led by the visionary activist Harry Hay—came together with a radical idea: what if queer people could see themselves as a community with rights, dignity, and solidarity?

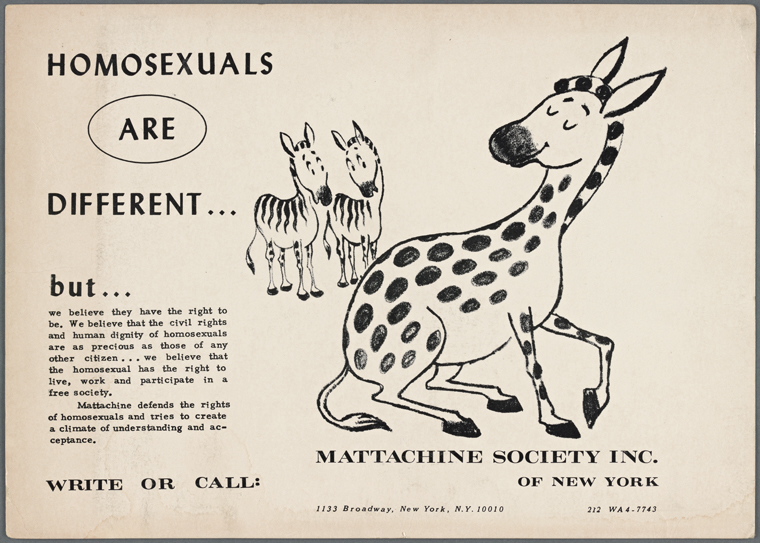

From that quiet circle grew The Mattachine Society, a groundbreaking group that helped launch the modern gay rights movement in the US. The spark they lit would ripple into generations of activism, law, culture, and community.

It’s hard to imagine Harvey Milk, the White Night Riots, the Castro, or the rainbow flags flying on Market Street without that first ignition.

Now, 75 years later, San Francisco is marking the anniversary with They Lit the Fuse!, a one-night program at the Main Library’s Koret Auditorium on November 13. The evening dives into the Mattachine story with images, rare archival materials, and even a John Wayne film clip—because, as the organizers point out, sometimes history is stranger than fiction.

The lineup is made up of queer history all-stars: Devlyn Camp, creator of the podcast “Queer Serial”; Will Roscoe, editor of Radically Gay; Jim Van Buskirk, founding program manager of SFPL’s James C. Hormel LGBTQIA Center; and Joey Cain, longtime curator and researcher. [In the late ‘90s, Van Buskirk and Cain worked to preserve the Harry Hay papers at the Hormel Center.]

All together, they’ll unpack how a hillside meeting in LA helped set the stage for what would later unfold in San Francisco.

Cain doesn’t mince words about what Mattachine ignited. “The exhilaration of freedom,” he says. “Freedom to live authentically and not on the false terms of religion, government, or society.”

That defiance was explosive in the days of McCarthyism and the Lavender Scare, when homosexuals were branded as threats and purged from public life. “Mattachine grew out of the possibilities of the New Deal and Socialist thought in the ’40s,” says Cain. “And let’s face it, we’re experiencing a new McCarthyism now.”

One of the group’s significant innovations was seeing queerness not as a shameful secret but as the basis of community. “They envisioned us as a unique community with constitutional rights,” Cain adds. “Before that, gays and lesbians didn’t necessarily see themselves as a minority with shared experiences.”

Their pledge was simple: no one crosses the “maelstrom of deviation” alone. Van Buskirk hears that as a reminder for 2025. “With today’s renewed homophobia and transphobia, Mattachine’s message of community, knowing no one is alone, is unfortunately a timely and vital message,” he says.

The Mattachine story might have started in LA, but San Francisco quickly became its second home. Van Buskirk points out that five years later, in 1955, four lesbian couples here—including Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon—founded the Daughters of Bilitis, the first lesbian organization in North America.

Their magazine, The Ladder, went nationwide, and by 1960, they were hosting the first national lesbian convention here. Meanwhile, after leadership battles tore through Mattachine in LA, Hal Call moved the organization north to San Francisco.

Call may not have the name recognition of Hay or Martin and Lyon. Still, Van Buskirk calls him essential for appearing on Berkeley’s KPFA radio in 1958 and in The Rejected, the first documentary about gay men on American television. He would also open Adonis, the first gay bookshop in the US, and later the first gay adult theater.

“Call is one of many important, if controversial, figures in our early history,” Van Buskirk says.

In a city that would later give the world Folsom Street Fair and the Castro Theatre marquee, it makes sense that even the movement’s messy chapters are still rooted in San Francisco.

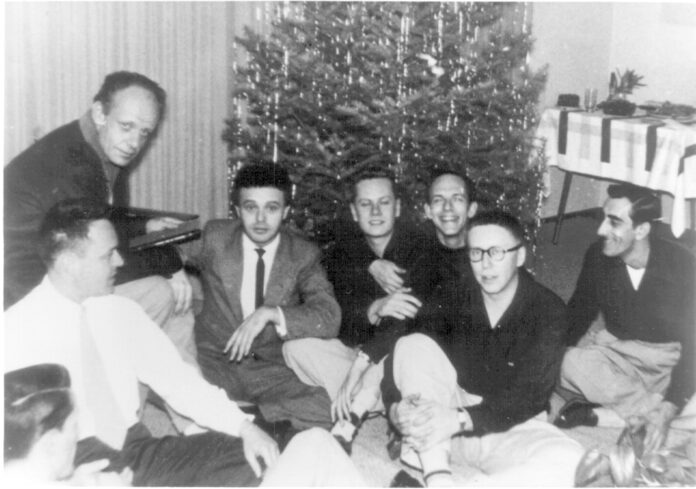

Keeping those stories alive has been a lifelong project for Van Buskirk. He points to one photo in particular—the only known image of a Mattachine meeting, snapped secretly by John Gruber.

“It remains iconic,” he says. “I’ll also quote from his unpublished manuscript so that people can hear his motivations in his own words. The Harry Hay Papers are another essential source.”

For Van Buskirk, archives aren’t just dusty files; they’re lifelines. “[Spanish philosopher, essayist, poet, and novelist] George Santayana said, ‘Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,’” he reads. “Preserving papers not just of famous people like Hay but also of a ‘regular Joe’ like Gruber lets us understand context from original documents.”

But even the best archives have gaps. The early record still underrepresents women, people of color, and other marginalized voices. Van Buskirk credits the women who succeeded him at the Hormel Center for pushing to fill those lacunae. In a city that has always prided itself on intersectionality, that work is far from done.

So what does progress look like, three-quarters of a century later? Cain sees a world transformed but unfinished.

“The cultural, social, and legal acceptance of LGBTQ people, the existence of identifiable communities, is a world we live in, at least in the US,” he says. “But the oppression, imprisonment, and murder of our people in many parts of the world is unfinished business.”

His words point to the paradox of progress: for every rainbow flag on Market Street, there are countless stories of queer lives still threatened.

Younger activists tend to encounter this history through podcasts, films, and social media, rather than leafing through old newsletters or court transcripts. That’s why Camp’s “Queer Serial” podcast has been so influential, layering archival audio with storytelling to make the past feel urgent. Van Buskirk says that’s the point.

“Engaging each generation via their preferred formats is essential,” he says. “I remember asking in 2008 why there needed to be a Harvey Milk biopic when there was already a powerful documentary. My partner said, ‘People don’t watch documentaries.’”

The recent film Fairyland, based on Alysia Abbott’s memoir about growing up with her gay father, poet Steve Abbott, shows how San Francisco’s queer history continues to ripple.

“Hopefully, some viewers will want to read her memoir, Steve’s poetry, and explore his archives,” says Van Buskirk.

For him, it’s all part of the same lineage: Mattachine in the ’50s, Daughters of Bilitis in the ’60s, Milk in the ’70s, ACT UP in the ’80s, marriage equality in the 2000s, and Fairyland in the 2020s. The through-line is memory, courage, and the refusal to disappear.

As They Lit the Fuse! unfolds in the Koret Auditorium, just blocks from the Tenderloin where Compton’s Cafeteria riot took place, and not far from the Castro rainbow crosswalks, the resonance will be impossible to miss.

“I hope attendees leave impressed by the courage of these pioneers, who paved the way for my generation—I came out in the early ’70s—and for everyone since,” says Van Buskirk.

The pledge the Mattachine founders wrote in 1950—that no one should cross the darkness alone—remains urgent in a time of anti-trans laws, book bans, and rising hate crimes.

Seventy-five years after a secret hillside meeting, San Francisco will honor that spark not as nostalgia but as fuel for the battles ahead. In this city, history comes out from behind glass—it marches down Market Street every June, it dances in leather at Folsom, it’s whispered in the stacks of the Hormel Center, and shouted from drag stages in the Tenderloin.

They Lit the Fuse! isn’t just about what happened on a hillside in Los Angeles. It’s about what continues to happen here—in the city that took that spark, fanned it into a flame, and still refuses to let it go out.

THEY LIT THE FUSE! November 13. Koret Auditorium, SF. More info here.