Anthony Riggs will tell you he hates paint. But he feels compelled to be an artist, nonetheless. He might even be a little obsessed.

“I hate the stuff. It’s sticky. It’s difficult to control. I get it in my hair. Paint is colored mud,” Riggs told 48hills.

Riggs will also tell you he loves paint. He calls it ancient magic that conjures up an impossible world that he couldn’t have imagined until it suddenly appears before him.

“I say to myself, ‘Did I do that? What does it mean?’ Then I think, I must be possessed by the ghost of Manet or one of those bastard Renaissance painters like Tintoretto,” he said.

At the end of the day he is exhausted physically and mentally, but knows that he will get up and do it all again tomorrow.

“It’s an exorcism and a catharsis. It’s something I need. Indeed, I do love paint,” he said.

Riggs was born and raised in the Bay Area. He completed his BFA (2011) in Painting/Drawing with High Distinction from California College of the Arts. He is currently part of the Benicia Artists Arsenal, a collective housed in a former military reservation located next to Suisun Bay.

He calls a day in the studio “a bloody, agonizing battle” and the subjects and themes of his work, once committed to paper or canvas, are forever trapped. Rendered inert and channeled from some other place.

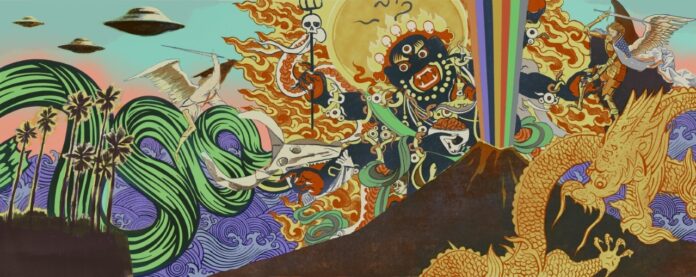

“Maybe I am receiving astral plane transmissions from an alien puppet-master from outer space. Or my Jungian shadow personality is taking over from the unconscious recesses of my mind. It would be nice to just paint quaint little landscapes with gingerbread cabins twinkling in the twilight,” he said. “But every time I try, a B-movie monster or some other obscenity rises up and cannot be ignored.”

Employing Surrealist techniques of automatic drawing and collage to generate new ideas, his works are sometimes inspired by dreams. Or watching too much television, doom scrolling Wikipedia, or random image searches on Google.

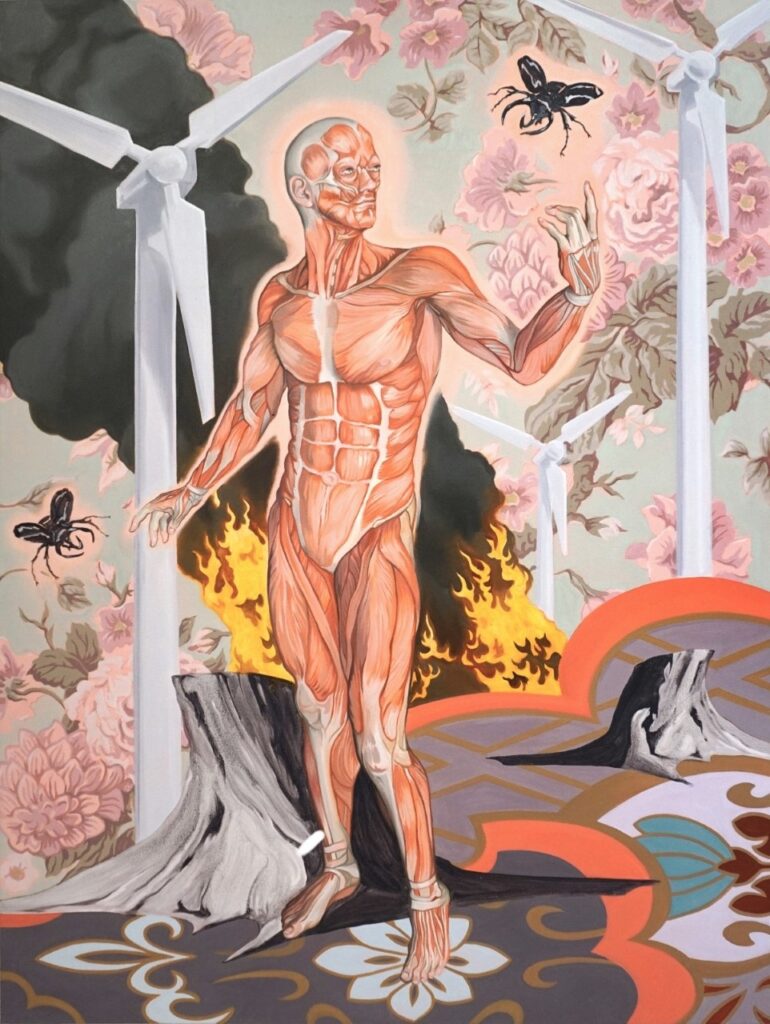

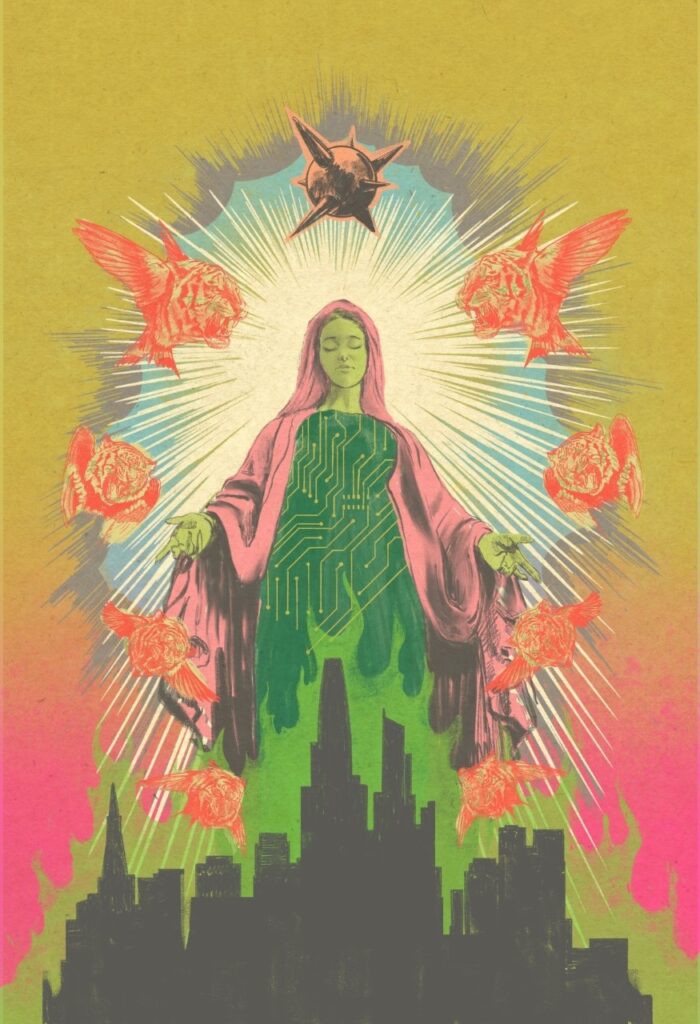

Usually, his process begins by making collages based on paintings by the old masters or from black and white historical photos. He’s looking for opposites in both composition—dark/light, thick/thin, bold/thin—and subject matter—east/west, science/religion, ancient/modern, technology/nature. His pieces, “Create the Past Rule the Future,” and “Every Act of Creation is an Act of Destruction,” (based on the painting “Virgin of the Rocks” by Leonardo da Vinci), are examples of this.

“I combine images from different historical periods and ideological viewpoints. I borrow from pop culture, religious iconography, and propaganda. These drawings and collages are then used as a reference for the final piece,” he said.

Once he begins painting, he tries to retain a sense of the original collage from different light sources. Other narrative devices he uses are strings, puppets, masks, stage sets, and flattened perspective. He does all this to emphasize the illusionary aspect of painting, employing beauty through pleasing shapes and colors to draw the viewer into what he calls, “The Spectacle.” His intention is to entice us into spending more time with a painting to extract deeper meaning associations.

“The relationship between the images I choose are purposely ambiguous, but they are not random. I don’t like easy analysis, nor do I appreciate being hit on the head with the hammer of someone’s personal ideology,” he said.

When starting from art history reference, Riggs gleans its purpose and place in time. He ponders the dominant ideology of the period and considers if the work was promoting this worldview or criticizing it. He then re-envisions how it could apply to our current times. His piece, “Fall of Eden,” exemplifies how science has become a belief system in popular culture.

“The fake plastic tree cell towers as axis mundi and center of knowledge—like the tree in the garden of Eden—or a satellite as the all-seeing eye, or the eye of God, that keeps a watchful view on us from above promising us doom or deliverance,” Riggs said.

He references playwright Oscar Wilde’s notion that the telling of beautiful untrue things is the proper aim of art. Riggs believes that the truth suggested in art is not an objective provable truth but one that exists in uncertainty and subjectivity.

“So. Art is a lie. But it is a lie that, according to Picasso, leads to truth. But what truth? Whose truth? My work has been an exploration of that very question. The problem is that art has been used throughout history by those looking to control the narrative,” he said.

If there is any truth in Riggs’ paintings, he says it lies in the very absurdity of the conflict it conjures up.

“If the proper aim of art is the telling of beautiful untrue things, then my paintings are lies, maybe even propaganda for some hard-to- put-your-finger-on belief system of chaos and uncertainty and, hopefully, the mystery of life to be experienced,” he said.

From his studio at a “top secret hidden location,” Riggs gets to work on revealing some truths. In purposely appropriating existing visual elements, he creates a dialog with the viewer about the origins of our beliefs and the conflicts that arise from them.

“Some of the most beautiful paintings in history were created to promote religious and political ideologies. I am interested in how the aesthetics of beauty and power have been used to influence that,” he said.

Riggs’ new series of work combines scientific and environmental worldviews with the aesthetics of ancient religious art. He is aiming to illustrate a link between archaic beliefs and modern thinking, for instance, the utopian/apocalyptic dichotomy shared by science and Christianity. It’s a reflection of what he views as the “pseudoscientific thinking, environmental fear, and religious beliefs” found in our day-to-day lives.

“In American mainstream culture, environmentalism has adopted a decidedly apocalyptic belief that the end of the world will be brought about by our own hubris. Like Christianity, there is a sense of doom and deliverance associated with our actions in the world. We hope for a green utopia, while simultaneously fearing an environmental apocalypse,” he said.

Like reading a lengthy classical novel, Riggs paintings take careful contemplation, and he demands that we take time with them. He notes the inherent irony in this, as he says no one has time anymore for such things. His process of painting is slow, and in turn he wants us to slow down, too.

“Even the ultimate understanding is not the goal. I create my work to be subject to the individual’s interpretation. I abhor easy readings,” Riggs said.

Regarding recent cultural conversation, Riggs says his work often deals with conspiracy theories, though he is not interested in spreading them. Rather, he is interested in the psychological and social implications. He sees his work as a kind of reporting. Instead of using words that communicate logically, he uses pictures that communicate metaphorically just what it feels like to live during the tumultuous times we find ourselves in.

And while Anthony Riggs contemplates what to reveal to us next, he hopes we engage his work in a particular way.

“I hope people experience catharsis, enlightenment, atonement, and immortality. In that order,” he said.

Riggs work is represented by Transmission Gallery in Oakland. For more information, visit his website at anthonyriggs.com and on Instagram.