It’s sadly ironic. No, wait—what’s the word? Kismet.

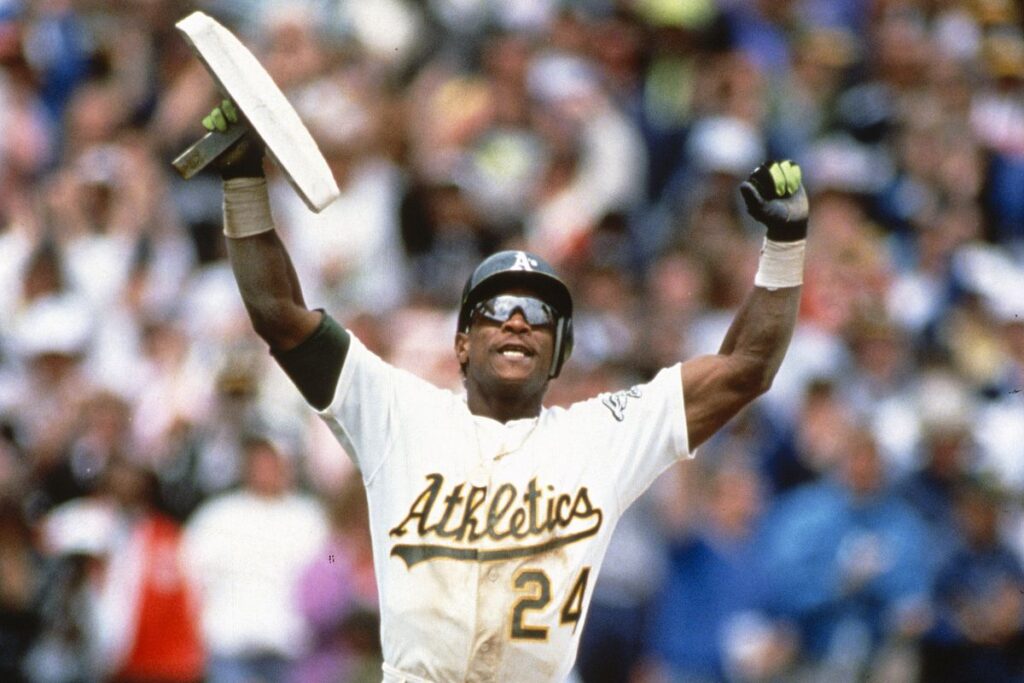

Yes. In the same year, the Oakland A’s ceased to exist and slumped along to the Sutter Health Park in West Sacramento, Rickey Henderson—arguably the Greatest Oakland A of all-time; a graduate of Oakland Tech in Oakland, California, where he played baseball, basketball, and football; an All-American running back with two 1,000-yard rushing seasons who played for the hometown baseball team in a 25-year career overflowing with so many superlative stats that it gave him the nickname “Man of Steal”—passed away Saturday, December 20, at the age of 65, just days before his Christmas birthday.

His numerous records, which he piled up like baseball franchise uniforms—he played for nine other teams besides the A’s—included the most stolen bases in a single season with 130 in 1982, the most times leading the league in steals with 12, and most consecutive years leading the league in steals with seven.

But, oh there’s more.

Yes. He was the greatest lead-off hitter in history and MLB’s all-time leader in stolen bases, leadoff home runs, and runs scored. But that doesn’t get to the greatness. This two-time World Series winner was a standout producer, performer, and personality on teams stacked with characters.

The ‘89 Oakland A’s—The Bash Brothers, Dave Stewart.

The ‘93 Toronto Blue Jays—Jack Morris, Roberto Alomar, Alfredo Griffin, and John Olerud.

If Reggie Jackson, another A’s all-timer, was the self-proclaimed “straw that stirs the drink,” then call Henderson the bartender, the bouncer, and the doorman.

According to MLB.com, Henderson was not only the 1990 AL MVP Award winner but also a 10-time All-Star selection, holder of two World Series titles, three Silver Slugger Awards, one Gold Glove Award, and the 1989 ALCS MVP Award. He was also elected to the Hall of Fame in 2009, his first year of eligibility, appearing on 94.8 percent of ballots. He won so many awards that at times it appeared he was just loaning them out between years before taking them back.

That’s how prolific his talent was. It’s a legacy that represented a living, breathing, base-path dirt-moving human sports statistic who was known worldwide for referring to himself in the third person as “Rickey”—and in modern times, would be making that $765 million, Juan Soto-type money, “fosho.”

Yes. Mark his passing as the final coda to a franchise that could never get that toilet smell out of their Oakland Stadium. Yet for years, before the vaunted “Moneyball” effect, that was the only thing that did stink while Henderson conducted his business.

And listen. John Fisher, principal owner of the Oakland Athletics? We don’t want to hear one ounce of that jibberish oozing out the side of your neck about sharing emotions of “sadness that our team will be leaving its home since 1968.”

Buddy. You are the one moving the team to a 14,000-seat capacity ballpark, one that Aaron Judge and Ohtani will just love knocking bombs out of, in anticipation of a Las Vegas stadium to be built and operational by 2027.

Save it.

How did Rickey master America’s pastime?

By planting the seed of the idea that the modern baseball player should be a complete athlete first. An action that penetrated the brains of millions of black and brown kids, some here in the States, many others in Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Cuba, and such.

A style of play he performed every day in his green and gold baseball cathedral.

Understand. This man was playing ball decades before we encountered the verbiage of analytics and metrics. Bill James, the writer, historian, and statistician who put “metrics” in the modern sports vocabulary said it best about Henderson: “If you could split him in two, you’d have two Hall of Famers.”

Better yet, when Rickey Henderson did that styling thing when he stole third base or hit a leadoff home run, it was with that take-my-time, gently pop-the-chain, and trot around the bases with a personification of coldness.

They were all viral moments. Decades before social media existed.

He was the precursor to the bat flip, the five-million ways to dap up your teammate, and every form of swag that has made baseball drip with popularity again.

Listen when Rickey popped that jersey rounding the bases in A’s stadium, Yankee stadium, Fenway Park, Dodger Stadium, or any of the stops on the Henderson Jersey Express around the league, it was Oakland first, that knew ‘that’s what’s up’.

But think about it: 25 years of playing baseball competitively. He began in 1979 when the first Sony Walkman was sold, and ended it in 2003, the year Sofia Coppola’s “Lost in Translation” broadcasted that a new Coppola master director was born, and a young Beyoncé charted a solo career with her “Dangerously in Love” album.

That’s a chunk of baseball people.

“For multiple generations of baseball fans, Rickey Henderson was the gold standard of base stealing and leadoff hitting,” Commissioner Rob Manfred said in a statement on his passing. “Rickey was one of the most accomplished and beloved Athletics of all time. He also made an impact with many other Clubs during a quarter-century career like no other. He epitomized speed, power, and entertainment in setting the tone at the top of the lineup. When we considered new rules for the game in recent years, we had the era of Rickey Henderson in mind.”

Such an era, indeed.