Executives from two for-profit property management companies acknowledged Monday that the residents of the Aliced Griffith Housing Project in Hunters Point aren’t getting the services they need, that elevators are still broken, that trash isn’t collected, and that many units aren’t habitable.

They also said they aren’t making enough money on the projects to do the necessary repairs.

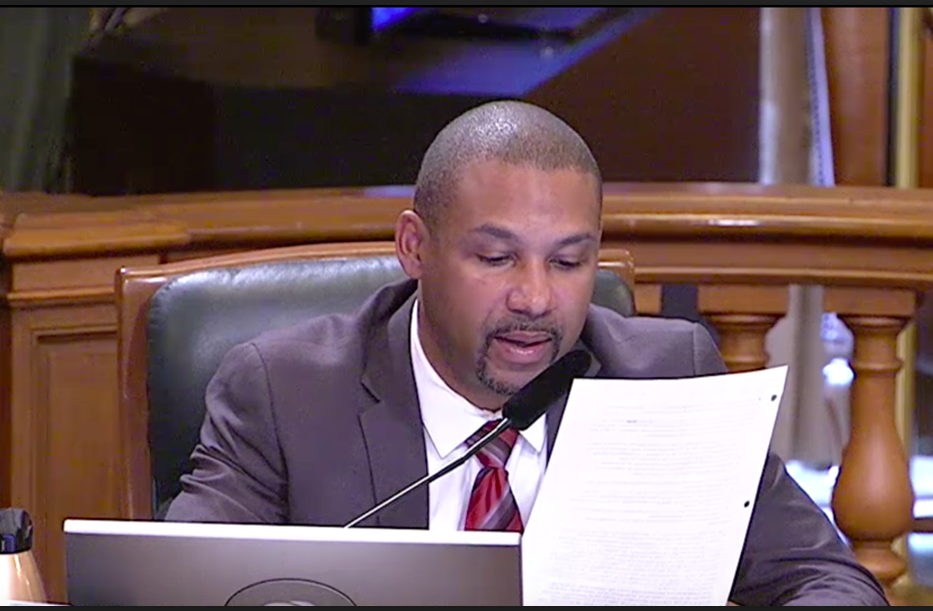

The hearing by Sup. ShamannWalton was a remarkable look into how the privatization of public housing has worked—and hasn’t.

In this case, McCormack Baron Salazar, a St. Louis-based company with more than $5 billion in assets that develops and manages housing, has a long-term contract to operate what was once a city-managed public housing project.

Since the city did a terrible job for years running it’s public housing portfolio, the federal government and San Francisco officials agreed to let private companies take over. While the city technically owns the land, MBS operates as the owner of the housing project.

MBS, in turn, hired the John Stewart Company to handle day-to-day management.

So: We have the Housing Authority, MBS, and John Stewart, all of whom can and did point fingers at each other, handling a situation that we can kindly refer to as dire.

Representatives for all three appeared at the hearing, but Walton focused on the two companies, asking repeatedly why they were unable to maintain, repair, and make habitable a project where mostly low-income Black people live.

Both Jennifer Wood, a John Stewart vice president, and Claudia Brodie, a senior vice president and MBS, initially blamed the COVID pandemic for the problems.

During the pandemic, many of the residents were unable to pay rent; that was also the case for many private apartment buildings and other public and affordable housing projects. So, if you look at this the way a private company would, revenue wasn’t meeting expenses.

That fact doesn’t give the owners of rental property the right to ignore pressing maintenance needs. In this case, though, that’s exactly what happened.

“We are dealing with extremely limited resources,” Wood said. She noted that a lot of the units are vacant—in part because they aren’t up to code. “The property does not bring in enough cash to cover its daily needs.”

Again: Lots of landlords faced this, many of them much smaller than MBS.

Walton asked Brodie why an elevator that serves people who in some cases are disabled, in wheelchairs, seniors, and unable to leave their homes hasn’t been fixed. The answer was astonishing.

MBS had asked an elevator company to make the repairs—but the landlord owed the company so much in back payments that the repair people wouldn’t do any more work until MBS caught up. “They told us we needed to pay $50,000, which we did,” Brodie said. But that was only a portion of the outstanding debt, and the repair company decided it couldn’t count on the landlord to make good on new expenses.

“So the elevator company didn’t make the repairs,” she said.

MBS and John Stewart are now asking the city for a loan to catch up on the serious maintenance problems that the tenants have been living with for years. That loan, Wood said, has not yet come through.

So the problems remain.

Walton asked Wood and Brodie both if, despite all these financial problems, they were getting paychecks. They are.

Walton: If you had a family member living there, would you be okay with it?

Brodie: Nobody’s happy with what’s happening there.

Walton: What I’m hearing from MBS and John Stewart is a lot of excuses.

He also noted that MBS sought out the contract to manage this property, and that John Steward voluntarily entered into an agreement to manage the facility.

When a public agency or a nonprofit runs into financial problems, there’s an expectation, not always fulfilled, that the people in charge will be accountable, and that, when it comes to basic human services, the taxpayers or the community are on the hook to make it work.

When a private, for-profit company enters into a contract to manage a housing project, there’s an expectation that the company will keep the place habitable, even if means losing money.

That’s not happening here. And the tenants continue to suffer, today.

“This is where we are right now,” Walton told me. “But we won’t let it remain the same.”