Workers at the Berkeley salvage yard Urban Ore kicked off an open-ended strike last week after they said staffing and wage concerns were repeatedly dismissed by management.

In April 2023, workers at the Berkeley business held a union vote, and collective bargaining began the following month. Conversations about wage instability and staffing issues began as early as 2021, according to Benno Giammarinaro, an organizer in the receiving department.

“At that time we weren’t fully thinking of ourselves as a union … we didn’t need an election to tell us that’s what we were. But 2023 is when we had our union certification election and then we began bargaining the next month in May,” Giammarinaro told 48hills.

Giammarinaro points to the pandemic as one of the conditions that set the stage for organizing. Urban Ore reopened as an essential business shortly after the initial lockdown and he said the surge in sales during the pandemic combined with the number of employees who didn’t return, created staffing issues.

“Before the pandemic annual revenue at Urban Ore was around $2.7 million, maybe a little lower. As soon as the pandemic hit, the annual revenue was $3.5 million. Thirty percent growth out of nowhere. It doesn’t happen just because prices went up. That’s because we were handling a much larger volume, a lot more customers and a lot more sales. Different work hours, different amount of staff. There were all these things changing all at once,” he said.

Giammarinaro noted that the influx of sales required new hires to learn on the fly, often forgoing formal training.

Beyond just that, the compensation at Urban Ore is unconventional, to say the least.

“When everyone has their onboarding and they’re told how pay works at Urban Ore, most people describe being a little confused or startled by how it’s done,” Giammarinaro said.

While it’s been described as a three-tiered system by owners and some media outlets, the reality is more like two. Workers get a starting wage of $21.50 which is decent compared to the Berkeley minimum wage but still significantly below what it takes to make a living in the Bay Area.

Beyond the base pay, workers get a share of revenue that is ostensibly added to their hourly wage. The third tier is a bi-annual share of profits, which has been stopped since the May 2023 collective bargaining began.

In practice, the revenue-sharing incentive creates an unstable wage structure for workers where their pay fluctuates each pay period in unpredictable ways. What’s more, workers don’t have access to the revenue for each pay period and thus can’t accurately calculate it themselves.

“They don’t provide weekly profits for us to do the calculations ourselves … They display the revenue totals each month but that’s not broken down by pay period. So we don’t actually see the revenue broken down into that pay period,” Giammarinaro told 48hills.

During collective bargaining negotiations, workers uncovered inconsistencies in the revenue-sharing formula and, they say, when they broached it with ownership, were dismissed out of hand. Additionally, ownership has been reluctant to provide any financial information that is legally required in such collective bargaining negotiations, like expenses for example.

“Our first proposal was $25 an hour starting wage … with a 3.5 percent annual cost of living adjustment and 5 percent raises from time of employment at specific intervals. They said right away, that’s way too expensive, that’s gonna bankrupt the company, that’s gonna drain our cash reserves in a year, all of these other things,” he said.

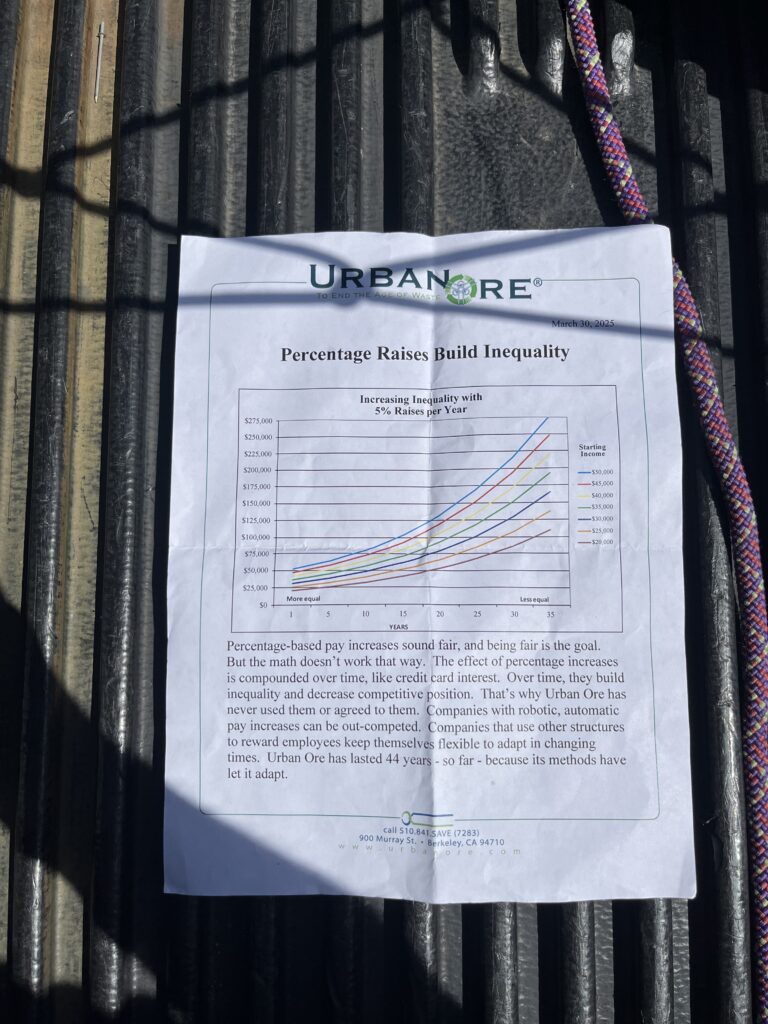

Owners Dan Knapp and Mary Lou Van Deventer claim the compensation structure is critical to Urban Ore’s success and draws workers to the job. This is a letter they posted:

Not so, as Giammarinaro puts it.

“They’re telling this to us. And we’re like this is not why we work hard. We work hard because we like what Urban Ore does and we like working together and we take pride in our work but not because of this shitty pay structure that you have,” he said.

We reached out to the owners, but they didn’t respond. In an article in Berkeleyside, Mary Lou Van Deventer, one of the owners, disputed all of the claims. She said after 40 years, she wanted to turn the operation over to a worker-owned co-op but have put those plans on hold.

A radical history of worker organizing

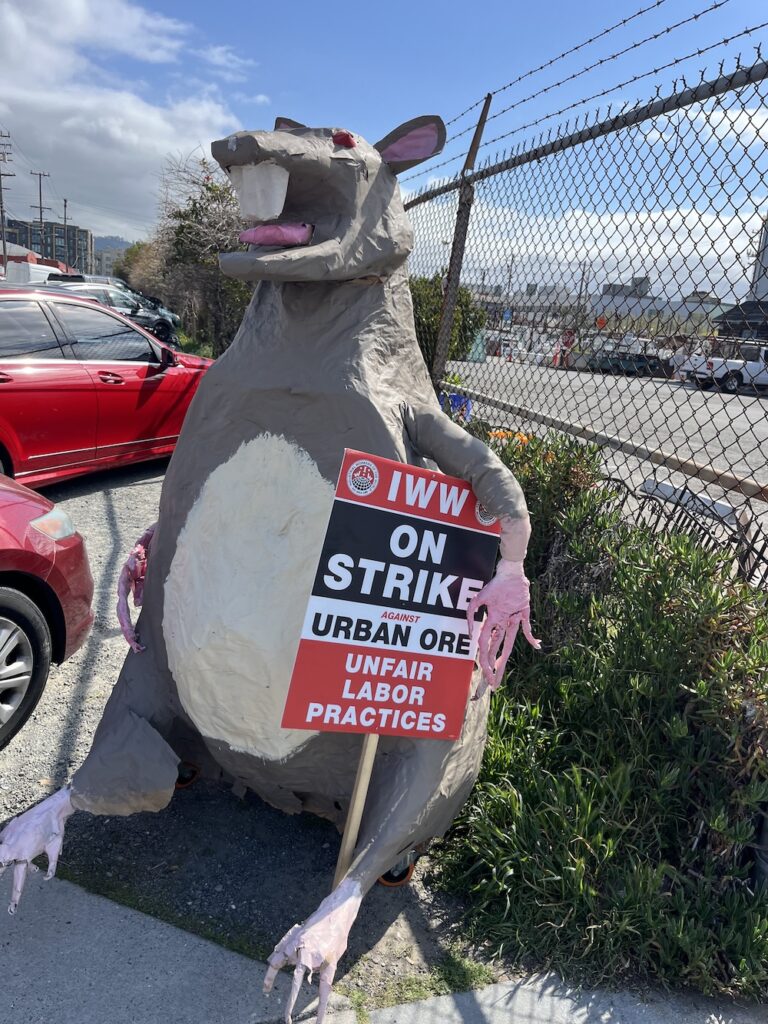

Urban Ore Workers voted to join the Industrial Workers of the World, and are now with local chapter IU 670. The IWW is one of the oldest and most militant unions in the country.

Historically, it was composed largely of immigrant workers and thus used different tactics than the more conciliatory unions like AFL. The Wobblies (a common nickname for the IWW) were more militant out of necessity. They didn’t have the voting rights that other white, American-born union members did. They weren’t able to participate electorally.

“If you were a woman or person of color, you couldn’t be in a union. The IWW was the first union to say not only can you be [in the union] but we want you to be leaders in that movement,” labor activist R. Scott Brown told 48hills in an interview. Brown has been organizing for more than three decades in the Bay Area with a variety of different unions, though his work is largely with the IWW now.

While large swathes of the East Coast and Midwest industrialized methodically, California’s settlement and worker development happened quickly.

The first worker-organized strike at the waterfront in the city was in 1886. The second strike, in 1893, was more violent with a Christmas Day bombing of a non-union house that killed 10 people.

Five years later, the City Front Federation was formed with 13,000 waterfront workers and the ensuing waterfront strike blossomed into a series of sympathy strikes before five people died in the fighting.

Despite the concessions to bosses, organized labor came out of the 1901 strike stronger than before. Even still, the Golden State sent just one delegate to the founding IWW convention in 1905 and five years later had just 1,000 members. The 1910s marked a violent climax for the IWW in California, with the 1913 Wheatland Riot in Yuba County and 1916 Longshore Strike in San Francisco.

The IWW opposed the racist Yellow Peril immigration policies and opposed World War I on imperialist grounds, thus drawing the ire of organized capital. Prominent IWW organizer Frank Little was lynched in August 1917 and the following month, the US government raided 48 union halls and arrested 165 members resulting in decades-long prison sentences.

“I think the proof was in the pudding with the fact that they threw seven international leaders in prison for saying WWI was bad,” Brown said.

Two years later, the Wobblies in Seattle famously took control of the city for five days before being met with violent repression. California owners and landlords took a lesson from that and, in 1919, passed the Criminal Syndicalism Law eventually resulting in 128 members being sent to San Quentin.

Union members continued organizing through the 1920s with Marcus Garvey helping to create the Universal Negro Improvement Association in 1920 with four million members and the eventual creation of Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in 1925.

“After WWII, the big red scares came around,” Scott said, noting that the perceived left wing boogeyman resulted in IWW intense repression.

Scott noted that first and foremost the IWW is a worker’s organization.

“I don’t wanna say the IWW is a left organization, its politics can be addressed that way. It is a worker’s driven process of organizing and empowering workers.”

Building on workers’ legacies

The strike was designated open-ended because of what the union calls management’s refusal to bargain in good faith and financial obfuscation by ownership.

Due to the unique nature of the compensation structure, union members say, management can easily inflate the numbers of total hours worked, thus lowering the hourly wage rate for all workers. Therefore, a worker gets punished if their coworker puts in overtime.

Giammarinaro said that the union’s figures suggest the company is quite profitable.

“So based on the profit sharing bonus in 2021, again this is with not the most perfect info, what we were able to calculate is that 2021 profit was somewhere in the ballpark of $750,000 which is pretty good for a business making $3.5 million in revenue,” Giammarinaro told 48hills.

Giammarinaro noted that they took the limited information they had and ran with it, developing a very granular financial analysis to determine what makes sense for all the workers.

“Our wage ask didn’t come out of nowhere, it came from what we knew to be profits in previous years and what we saw as the trajectory of the sales revenue of the business,” he said.

As Giammarinaro and other workers told me, they’re flexible and willing to adjust their demands as needed but not without verifiable data to back up management’s claims. At the time of this writing, the strike is on day 10.

“We called this an open-ended strike for a reason. It needed to be one,” Giammarinaro said.

The IWW is an organization that, in more than a century of organizing, has secured the most cumulative and impactful concessions for workers. Urban Ore’s strike is a continuation of that powerful legacy.

“This is a worker-driven strike,” Brown said of the now nearly two week long strike. “This union is done right, they understand that they’re responsible for their own liberation.”