Like many children of the late ’90s and 2000s, I grew up reading video game magazines. Glossy periodicals like Nintendo Power and Electronic Gaming Monthly were how I first came to understand video games, not just as fun ways to pass the time, but as works of art created by professionals within a specific industry and cultural context.

But over time, print media gave way to the more diffuse constellations of gaming information sources across the internet ecosystem, while modern games grew in different directions. How can we track down the ideas and conditions that created the contemporary gaming sphere? What knowledge might have been lost?

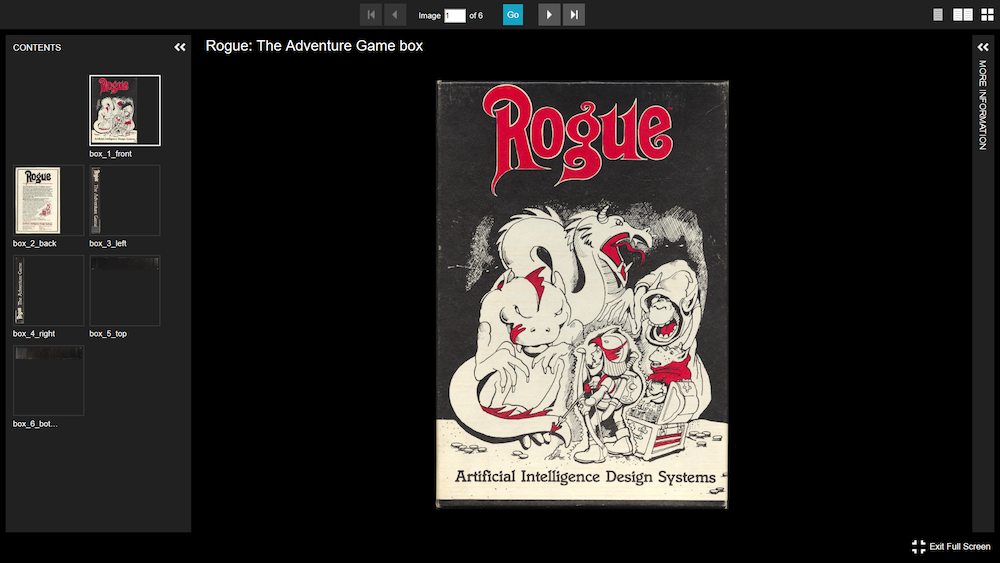

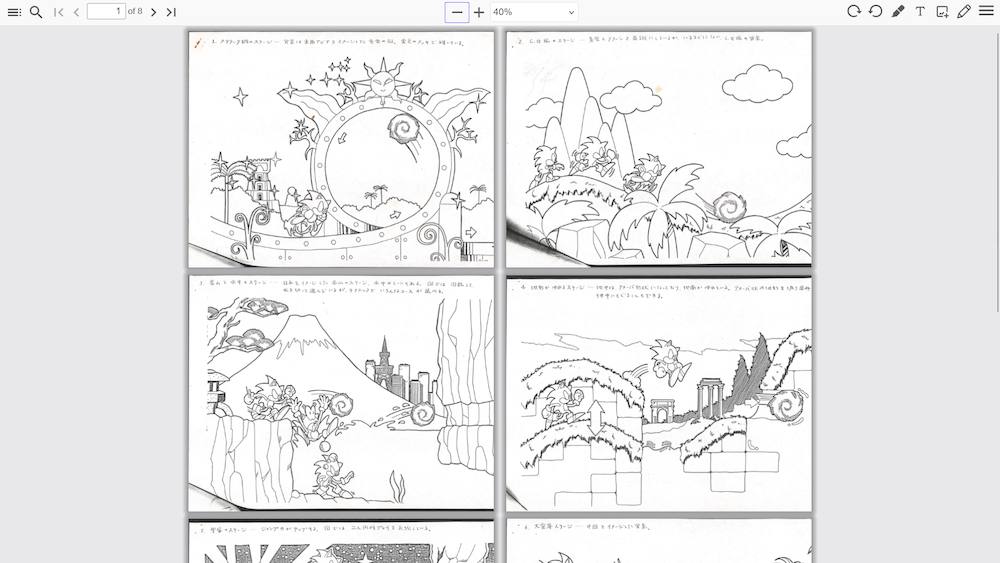

The Emeryville-based Video Game History Foundation is a nonprofit organization devoted to preserving documents relevant to the history of video games. On January 30, the Foundation launched its ambitious digital library, which makes its wealth of materials accessible to anyone with a working internet browser and provides a more organized alternative to the messy and piecemeal forms of preservation found elsewhere online. Moreover, the library includes behind-the-scenes documents from important developers like FromSoftware and Cyan, and rare materials that aren’t collected anywhere else.

I spoke with founder and director Frank Cifaldi and library director Phil Salvador about the origins of the digital library, their hopes for the future of video game history preservation, and stalking people to make documents available.

48 HILLS I’m gonna start with the biggest question. What is the mission and methodology of the Video Game History Foundation?

FRANK CIFALDI The mission of the Video Game History Foundation is to elevate the world’s understanding of the history of video games. It’s an undeniable fact at this point that video games have had a very significant impact on culture. What we’re aiming to do is make sure that the history is understood. Our way of doing that is capturing the materials that people who want to tell the story of video games would need. If you hand a kid Super Mario Bros., they might have fun, but they’re not going to understand why it was historically significant. We collect material that relates to how games were made in their time—who made them, why they made them, how they were sold—but also we try to capture the culture. So our best way of doing that for ye olden days, the ’80s and ’90s, is capturing all the magazines that reviewed games, so you get a broad overview of how people approached the game in its time.

PHIL SALVADOR There are folks who have been collecting games and gaming history, there are museums and archives, but there hasn’t really been an organization whose sole focus was this subject. The Smithsonian collects video games, but they’re not going to video game companies and lobbying for reform to make video game history more accessible. When people ask what we do, I often say that we’re trying to make video game history better. We’re the organization that’s trying to help make this stuff more accessible and chart a brighter course for the future for this medium.

FRANK CIFALDI We’ve done so many elevator pitches. “Level up video game history!” [laughs] Our understanding of video game history is lacking, and we don’t think it’s the fault of the researcher, we think the tools suck. We’re making tools that don’t suck.

48 HILLS I was curious about what the impetus for developing the virtual library was.

FRANK CIFALDI Boy, that’s a question that could go back 25 years for me. I was interested in the history of games, and I was writing things on the internet about game history and I needed reference material for that. And I was frustrated that none of my local libraries in Las Vegas held on to video game magazines, which is something I would need to understand things as basic as when games came out, you know? So I started building my own personal library. As the years went on, a lot of that material ended up being online in one form or another. But copyright wasn’t necessarily respected, which is just reality with historical preservation. The other end was traditional archives. The most famous one would be the Strong National Museum of Play in Rochester, New York—which is onsite only. You have to book travel to Rochester, you are limited in time by what you can afford, and you are handling paper material. We felt that there was something needed in-between.

PHIL SALVADOR My mom says, “The internet is the world’s greatest library, where every book is in a pile on the floor.” And we felt like we could do better than that. As we’ve been adding material to our library [and] developing the platform for it, it’s always been informed by, “What is the user experience? What are they looking for? How does someone want to do research?” Everything from how we designed the search box on our website to what sort of tags and metadata we put on the individual items. One of our big collections we launched with, the Mark Flitman papers, was delivered to me as a giant .zip file. [We] make this into a tool for research, not just a bunch of files.

48 HILLS Hearing about the process of putting it together, I was wondering what are the things that you had to create wholesale in order to make this work?

PHIL SALVADOR I can do traditional library archiving, but a lot of the formal structures didn’t necessarily match what we wanted to do with the materials. We’ve had to adapt those as we went. We’ve also had to figure out how to make things accessible in the way that historians need. If you’re researching video game history, you’re probably looking for specific projects, developers, or time periods. So we had to figure out how to make all of our magazines full text searchable. Which might sound easy—there is technology that does that—but designed to work on dark fonts on light backgrounds, and not on whatever was going on with 90s graphic design for video game magazines. It’s been a real buffet of solutions for figuring out how to make all the materials available. And I think, for the user, a lot of that work is going to be invisible. They don’t see the years of figuring out what standards we were trying to follow to actually make this stuff accessible.

FRANK CIFALDI We’re trying to build a tool that anyone can use. I think people who are deep in this world, like me and Phil, take searching through documents for granted. But this is new to a lot of people, even people who are really deeply embedded in this stuff. I know someone who’s an editor for The Cutting Room Floor, where they investigate games to find cut content [and] look at magazines to find early versions of how the game evolved. I’ve had that person come to me finding all this new material, and actually, the scans of the magazines have been on the internet for 15 years. [laughs] You just didn’t know that because you couldn’t search them before. We’re democratizing video game history research. We’re making tools that anyone can use, using the most current technology there is. This is the most usable digital library of any institution.

48 HILLS Do you see this as inspiring other libraries or other historical preservation organizations to kind of follow along in what you’re doing, or do you see this as something separate? Or neither?

PHIL SALVADOR Libraries, archives, and museums tend to be conservative in the sense that they’re not taking a lot of risks on things. What we’re doing is something that is a little bit riskier on paper, applying fair use a little bit more boldly. We are pushing the envelope in a way that can hopefully serve as a positive model for others. What I’ve been really excited about since we launched is that we’re seeing the library inspire people to think like historians. We’ve seen a lot of people who come to the digital library and say, “Oh wow, here’s this thing from an old game I like.” But then, they’ll notice something else, or they’ll notice an interesting phrase or an interesting collection. And they’ll start exploring a little bit more. We are inspiring people to do creative research, and that then begets better preservation and access, and that’s a positive feedback loop.

48 HILLS Do either of you have a favorite document or series of documents preserved in the library?

FRANK CIFALDI That’s a hard one for me, because I did almost all of the collecting. Almost anything that’s here, I have a cool story about.

PHIL SALVADOR Pick your favorite baby. [laughs]

FRANK CIFALDI I don’t know if this is the answer, but it’s the first one that comes to mind. We have a newsletter in the archive right now called The Logical Gamer [from] the early ’80s. It’s actually pretty insightful [and] has some really historically interesting material, like photographs from trade shows in the early ’80s. The editor has unfortunately been dead for a very long time. There were something like 17 issues, and two or three were located and scanned online, and that’s it. We tracked down the editor’s best friend and got in touch with him, and he’s like, “Yeah. This was really important to me and so I saved it.” He was able to loan us this one-of-a-kind material to scan. It’s so representative of what sets us apart. We can spend the time stalking men online until they loan us things. [laughs] But the other thing is that we don’t operate under a conservative traditional library structure. We can borrow things, digitize them, and let people read them. And that’s something that is really rare in the world.

PHIL SALVADOR There is a concept called post-custodial archiving, which is the idea that archives don’t need to take in the materials for themselves, they can help provide the resources to make those things scanned and accessible. I think we’re one of the first libraries that’s starting with post-custodial collections as the foundation. Another great example, which is my favorite collection, is the Cyan collection. The creators of the video game Myst have been an independent company for over 30 years, and they’ve kept everything. Everything they’ve filmed, every time they were behind the scenes with a camcorder, they just kept it in their storage room. We jumped in and were like, “Can we work on that? Can we digitize that?” And they gave us the rights to redistribute these videos. It’s incredible. Myst is a video game that’s always meant a lot to me. And being able to share them and see how well the community responded [has] been such a rewarding experience, and a great example of the sort of embedded archival work that only a scrappy organization like ours can do.

48 HILLS How do you see the library growing moving forward, and what role do you see it playing in the broader project of video game preservation?

FRANK CIFALDI Even within our existing collection, there is a near-infinite amount of growth. I think the current digital archive represents maybe five percent of our collection. And that’s not for lack of trying—this is real work that it takes to populate something like this. This stuff takes time. Longer-term, we’re a really fluid organization. Anyone who’s interested in video game history, we’re going to continue evolving with what their needs are. Right now, the biggest needs tend to be document access, so that’s where we are. I don’t know where that’s gonna be 10 years from now, but we’ll hopefully be young and spry enough still to respond to it.

PHIL SALVADOR In terms of the library, I think it’s quickly become our calling card. A lot of people know that we are working on video game history, and they’ve liked that for years without really having a tangible product associated with that, for lack of a better word. Now that we have the library open, people have come back to us and said, “Okay, I get what you’re doing now, let’s talk.” We’re hoping that opens doors, not just with individuals, but also with companies. We’re able to provide access in a way that’s respectful to them and not just the pile of books on the floor that we talked about earlier. I’m really excited about what’s going to come out of that.

VIDEO GAME HISTORY FOUNDATION for more information, go here.