Through photographic prints, artist Ashima Yadava is a visual storyteller who reflects the world around her in social commentary and sensitive imagery. Bearing witness to recent interconnected events around the world, coupled with the hypocrisy of Western politics and the coldness of the liberal response, Yadava says she has been changed in ways she is still trying to articulate through her work. She feels a sense of urgency to show things not only as they are, but also in how they could be.

“It is an incredibly painful time, the reference point has forever shifted, and I feel complete despair at the brokenness of the system, my own complicity in it, and the need to fix it,” Yadava told 48hills.

Yadava grew up in New Delhi, India and arrived in San Francisco nearly two decades ago. Her purpose was to further her education, with a deeper intention to put distance between herself and imposed dictates for women.“It was only months after I moved here that I realized the United States had its own set of gendered expectations and constraints,” she said.

Yadava began her creative journey as an assistant to a filmmaker after her undergraduate studies were completed in Delhi. This was her introduction to visual storytelling. “We spent a year filming She’s My Girl in remote villages in the northern state of Haryana in India, documenting stories about female infanticide. I remember being completely shaken by the reality of what was going on. It was a pivotal moment for me, realizing the power of film to tell stories that no one wanted to talk about.”

After moving to the United States, it was imperative for her to “keep up the fight” against the same colonial systems that exist here in different forms.

“I was shocked to find that child marriage was legal in all 50 states at the time, putting millions of girls at risk every single day. I became involved with Maitri (a Bay Area nonprofit that aids survivors of domestic violence) as an artist-advocate, and with their help, I started documenting stories of survivors in the South Asian community in the Bay Area,” she said.

Yadava understood then, as she does now, that the camera grants the opportunity of photographing someone’s life, a privilege that rests on a foundation of trust that she must honor and represent with care.

In 2020, as a Director’s Fellow in Documentary Photography from the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York, Yadava began combining photography and printmaking to create narratives that reflect her multicultural experience. From her current work space in the Cubberley Artist Studios in Palo Alto, Yadava begins her day by checking a to-do list and pending deadlines. In a light filled space, she develops sketches as story maps, finding room to experiment, to fail, and try again.

After years in the Bay Area, she still values that one can find counter-culture movements in every corner and neighborhood. Currently living north of the Panhandle, her first home was in the Haight.

“My place was right by the gigantic legs with red heels sculpture by Barry Forman! It fit the image of San Francisco I had imagined because it said you can be weird here and no one would judge. Haight-Ashbury has given birth to so many social movements and continues to be so welcoming to people, which I have come to appreciate,” she said.

She notes resonant entities that have contributed to that culture, including Colpa Press, National Monument Press, Auspicious Books,friend Shao-Feng who co-founded Cademy, zine makers, and experimental art incubators Red Poppy Art House and the newly opened TnT Art Lab.

“I appreciate the space the Bay Area provides to breathe and work in quiet while also giving you enough to engage with, in ambivalent, obnoxious, rebellious and meaningful ways,” Yadava said.

In describing her own work, Yadava uses the words reciprocal (as collaborative social practice), confrontational, and boundless. In fact, her name Ashima comes from the Sanskrit word aseem, which means without limits. Yadava says that everything she does has been influenced in some way by her upbringing in India and all that she has carried since.

“Whether it’s my sensibility as an artist or how I see the world, my perspective is rooted in where it all began. As Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti says, ‘The fish, even in the fisherman’s net, still carries the smell of the sea,’” she said.

She attributes this sway to the experience of growing up in Delhi in the 1980s and ’90s and an immersion in a deeply multicultural city that celebrated differences and embodied historical depths and complexities. Evenings were spent listening to Abida Parveen performing at historical sites; imbibing the sounds of qawwali (Sufi Islamic devotional singing) swirling in hypnotic rhythm; and watching live theater created by progressive writers like Ismat Chugtai, Premchand, and Saadat Hasan Manto.

Yadava says that living in the sociopolitical milieu of Delhi at that time was foundational and taught her that traditional/modern and East/West could coexist. Reading the works of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Toni Morrison, and Salman Rushdie in her teenage years also held influence on Yadava. The blend of reality with surrealism as a form of political and social critique was transformative.

Her earliest visual understanding came from paintings by Indian modernist artists of the 20th century. “In the aftermath of colonialism in India, Jamini Roy’s reclamation of indigenous forms, with their earthy colors and simplicity, gave my generation a new lexicon, as did MF Husain’s bold strokes, his celebration of Indian identity, and his desire to experiment. Amrita Shergil’s empathetic portrayal of ordinary Indian women accorded them dignity and showed me how to bear witness,” she said.

About her own training in documentary photography, Yadava says it felt incomplete, with a mostly Magnum-era framework that “valued neutrality over nuance” so she allowed other influences to seep in.

“It was through Carrie Mae Weems’s images that I began to understand the presence of silence, and all that is hidden. Through Dayanita Singh, I learned that photographs could be objects. Through Gauri Gill, Jim Goldberg, and Susan Meiselas, I understood that other people could have agency in your work. This is the constellation of artists that influenced me initially, and I feel that where they left off is where my work comes in,” Yadava said.

She adds that photographers Justine Kurland, whose work embodies freedom; Pamela Sneed whose practice she finds fearless; and LaToya Ruby Frazier, who allows humanity to lead her, as artists who were also instrumental in her development. Though centered in photography, Yadava integrates other media to best represent conceptual subject matter.

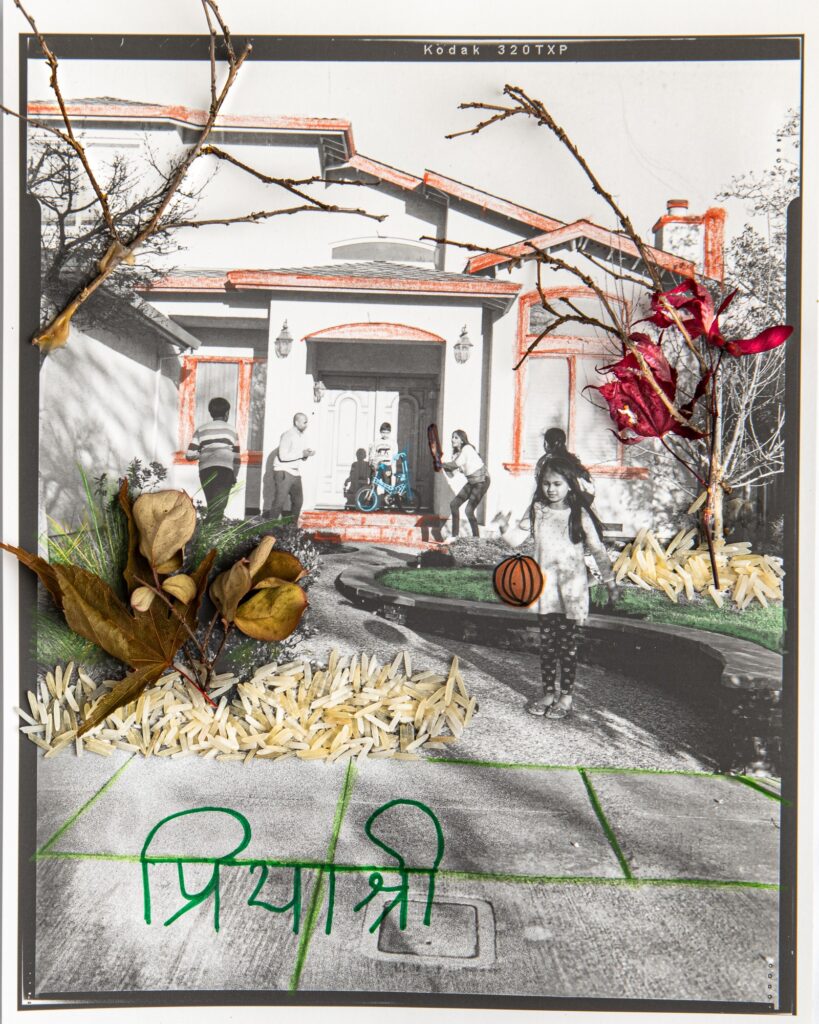

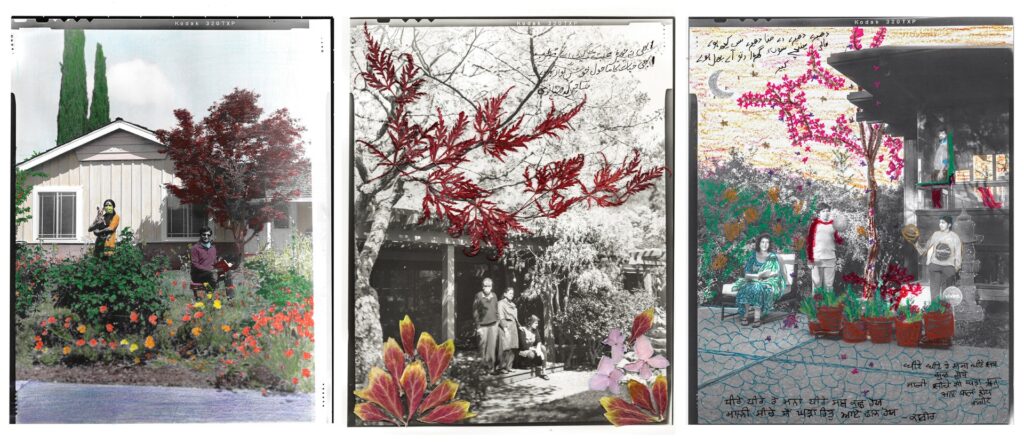

“When I began working on the Front Yard series, the slow pace of using a 4×5 large-format camera gave me time to reflect on my role as a photographer. I had seen India represented a certain way through images shaped largely by the Western male gaze, making me very aware of the problematic one-sided perspective that is synonymous with documentary photography,” she said.

In order to disrupt that dynamic, Yadava invited the families she photographed to intervene—to color or embellish the black and white images freely and determine how they wished to be seen.

“In Front Yard, collaboration becomes a mechanism of equity, offering a more in-depth conversation about perceived realities,” Yadava said.

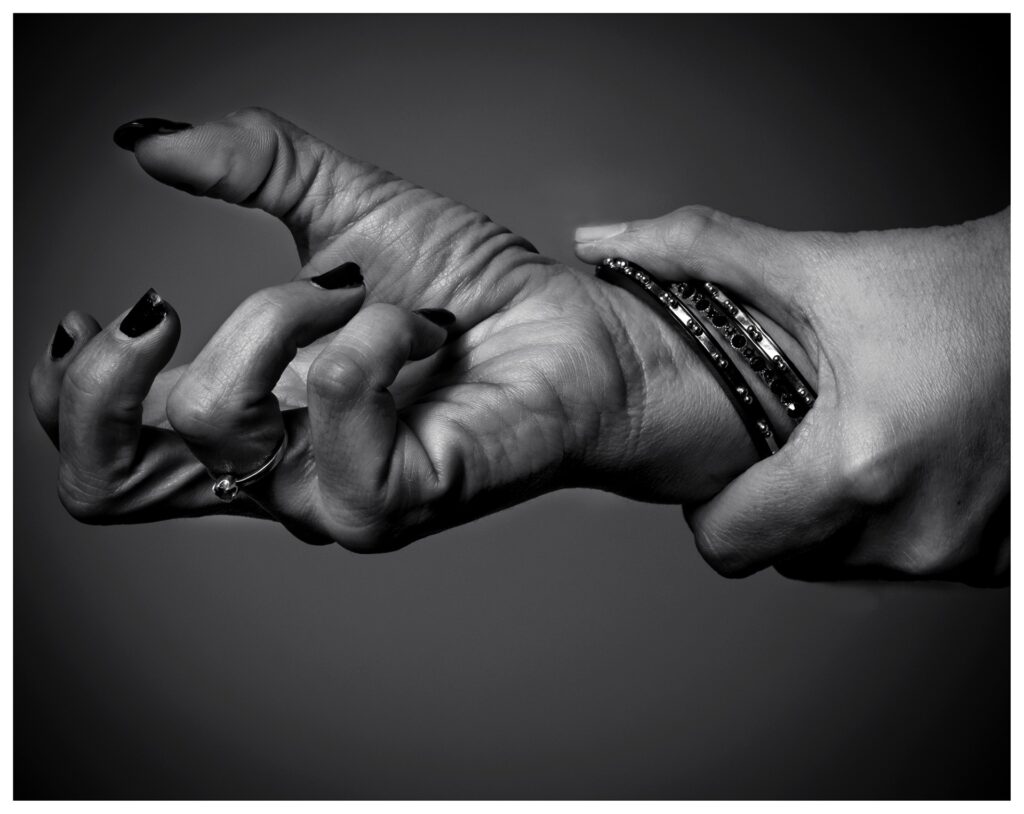

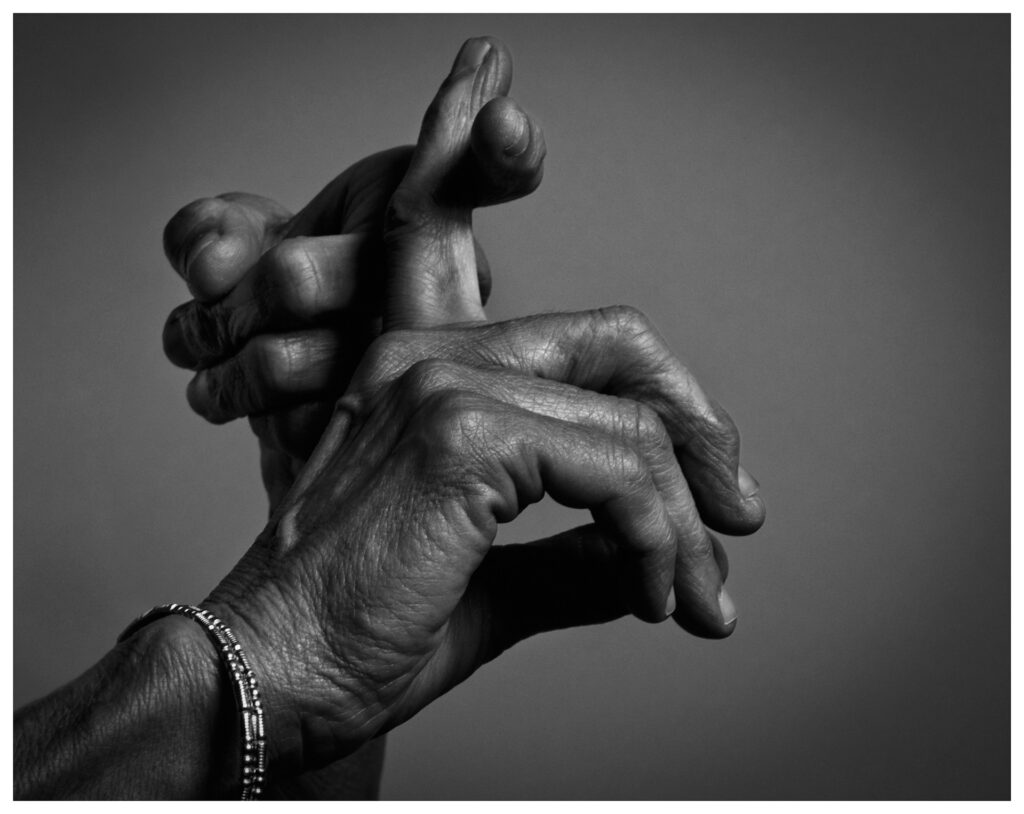

In another series, If Hands Could Speak, Yadava came to understand the complexity and delicacy that comes with photographing domestic violence.

“I believe that how you say something is as important as what you are saying. In an effort to provide more agency while also protecting identities, I began exploring the symbolism that their hands offered. Hands are equal parts the agents of oppression as they are the actors of revolutionary movements and change. Each person I photographed used their hands to articulate their feelings or state of mind,” she said.

Yadava also recorded individuals’ audio testimonies, envisioning the series as a public art installation that would appear in places like bus stops or on billboards in order to amplify the voices of domestic violence survivors while highlighting the important work of community organizations like Maitri.

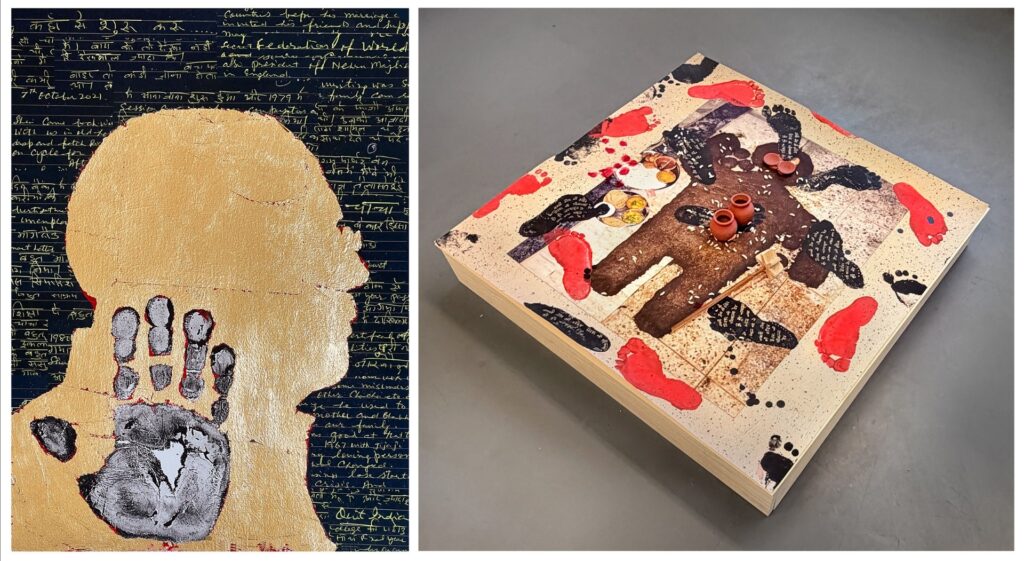

In recent years, her practice has expanded into curatorial and publishing work. Overcome with anger and disbelief in the wake of the overturning of Roe v. Wade, Yadava conceived the project, Huq: I Seek No Favor, as a call to action.

“Huq is an Urdu word meaning rights and the phrase ‘I seek no favor’ is taken from Audre Lorde’s poem, A Woman Speaks. I also took inspiration from Chilean poet Cecilia Vicuña’s declaration, ‘Tu rabia es tu oro’ (your rage is your gold),” Yadava said.

In 2023, she launched a newsprint edition of the project as a testament to our collective rage. Now in its second iteration, Yadava continues to collaborate with individuals, universities, colleges, art and community spaces, to present teach-ins, panel discussions, and readings. Huq is currently on view in the show Flashpoint! Protest Photography in Print, 1950–present, at the Hirsch Library, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas, through January 24, 2026.

Recent group shows include, The Matter at Hand: Improvisation in Art and Civic Life, at Brant Gallery, Massachusetts College of Art and Design (Boston), Echoes of Dissent at Disruptive Studio in New York, and inclusion in the ongoing collective of Body Freedom for Everybody.

Yadava is busy preparing for a solo exhibition of the Front Yard series at Chung24 Gallery in San Francisco, which runs from January 7–February 14, 2026. Thought the series has been shown internationally, this marks its debut in the Bay Area. She’s also working on a new project that uses water as a metaphor to talk about the fluidity of our lives, our interconnectedness, and her own place in it.

“A recent conversation with my friend Alberto Duman reminded me of the Toni Morrison quote, ‘All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was,’ which is very apt for this moment. I have also been thinking a lot about how geography is destiny, especially as water continues to be used as a political weapon,” Yadava said.

As artist Ashima Yadava moves forward in her life and work, she hopes to inspire critical examination of what an image holds and elicit conversations that extend beyond gallery walls.

“If my work can spark dialogue that leads to policy changes and encourages direct engagement with urgent social issues, it would have achieved its full potential.”

She is also thinking a lot about identity, particularly in relation to movement from one culture to another.

“When you uproot yourself from a place in search of other horizons, there is a kind of hyper-awareness that follows. You are acutely aware of your place and how you are being perceived or judged. It is the kind of double consciousness, as WEB Du Bois said, that one lives with, where you are being yourself while also performing yourself for the dominant gaze.”

In some ways, her two worlds collide: Classical arts are anchors for Yadava, reading Urdu poetry and learning Hindustani classical music as a form of meditation. As the Chair of Programming on the board of directors at SFCamerawork, she is helping to reshape and reactivate the photography scene around the Bay Area into a more collaborative whole.

“While Delhi gave me a solid foundation, it is San Francisco that gave me the space to speak my truth and be fully myself,” Yadava said. “It is a difficult moment for a lot of people with heart, and one may feel disillusioned, but this city has time and again refused binaries and shown me it is possible to create new systems that are built on care and solidarity.”

For more information, visit her website ashimayadava.com and on Instagram. Huq can be viewed here.