While creating works in the vein of American Realism, defining what his paintings are about in mere words is a challenge for artist Jonathan Crow. It’s his opinion that visual art, like music, works best by evoking feelings or ideas that don’t resolve easily into words.

“My art feeds the intuitive rather than the rational. But if you were to put a gun to my head, I’d say mood, composition, and color are three words that describe my work best. When I’m painting, those are the three elements I’m most focused on,” Crow told 48hills.

Crow might consider himself a movie nerd or even somewhat of a dilettante, having completed two degrees in film, (BA, Boston University; MFA, CalArts), and another master’s in Japanese Studies, but as a painter largely self-taught, apart from participating in a handful of workshops, he is living the life he’d only imagined.

“I spent most of my 20s avoiding life by going to grad school. Not a strategy I’d recommend,” he said.

Growing up in rural Ohio, Crow bounced from Boston to Japan to Ann Arbor, Michigan, during his 20s before landing in Los Angeles, where he lived for a decade and a half, working in the film industry. His move to the Bay Area 10 years ago was prompted by his wife accepting an alluring job offer from a large tech company. Currently living in Santa Clara, Crow loves how welcoming and down-to-earth the Bay Area art scene is.

“As I was just starting, I found more than a few better-established artists than myself, and curators, willing to talk with me. I really appreciated that,” he said.

The works of Edward Hopper, Richard Diebenkorn, and the films of David Lynch are huge influences on Crow’s work. An even bigger sway was time spent visiting his grandparents in suburban Southern California in the 1970s as a young boy.

“Northwest Ohio, where I grew up, is flat, rural, and, for much of the year, very grey. San Diego was completely different. I have distinct memories of being impressed with the mountains, the palm trees, the browns and yellows of the landscape, and most importantly, the intensity of the light. My two grandfathers died when I was about seven, and then my grandmother moved to Ohio soon after, so my time in California as a child probably totaled a couple of months,” he said.

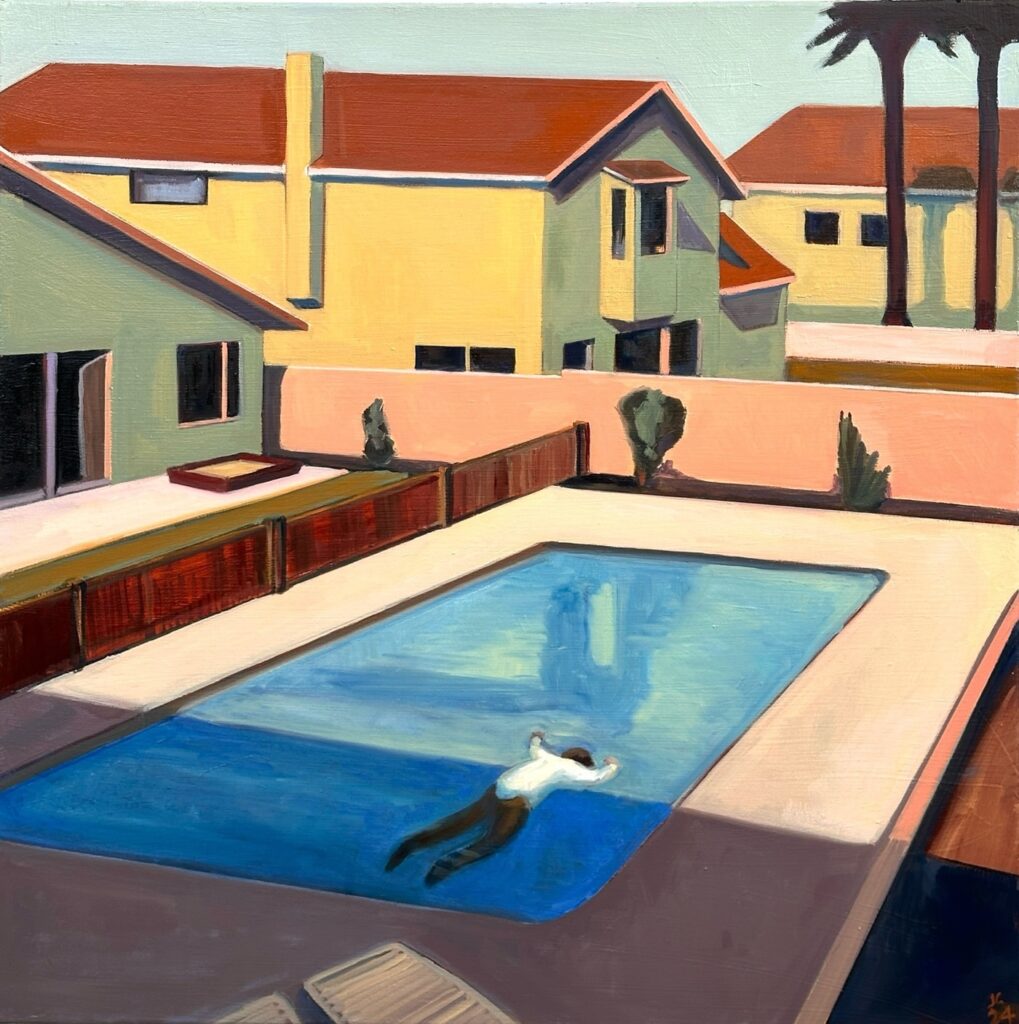

Though it was a brief amount of time in the scheme of things, Crow recognizes its impact on him, saying it was “like an iris opening to expose a piece of film.” The selection of paintings for his first solo show, Cul-de-Sac, running through May 3 at the Triton Museum of Art in Santa Clara, was influenced by those formative visits in the 1970s. One painting where this connection is evident is Chuck and Cindy Plus 2.

“I was inspired by a photo from 1976 of my family in front of my grandfather’s house in San Diego. That little kid in the middle of the painting is me as a four-year-old. I think the photo and the painting capture that haggard look of all parents of young children,” Crow said.

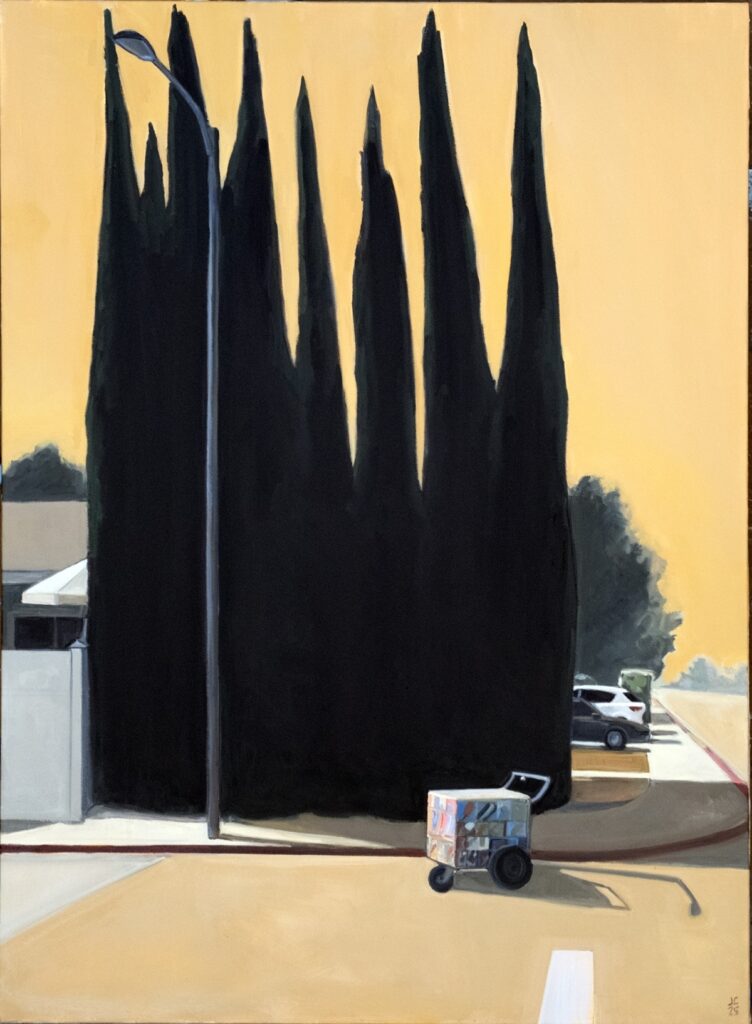

A second painting, Enrique’s Cart, shows the suburb in a less nostalgic light, the subtext being what happens in places we consider safe, idyllic havens of Americana.

“The kernel of this work was a photo I saw in the news of an abandoned ice cream cart. ICE had swooped down and kidnapped this poor man named Enrique, leaving his cart, his livelihood, behind. Like a lot of people, I’ve been watching the news, oscillating between feelings of cold fury and low-level panic. There was something horribly poetic about that cart that resonated with me,” Crow said.

Crow’s process relies on composition from the start. After spending some time with it, if the composition is not strong enough, he finds himself “soon adrift on a sea of tears.” He eventually seeks resolution by replacing a conflicting element in the source photo with something else that works. For example, while staying with his in-laws in Los Angeles, Crow’s attention was caught by an image that resonated for Enrique’s Cart.

“Across the street was a house that was almost completely ringed by these giant, looming cypress trees. They looked menacing, almost like the maw of some fanged monster. It occurred to me that those trees would be a very fitting background for that abandoned ice cream cart,” he said.

Another example is Crow’s background treatment in the painting, Chuck and Cindy. When the houses in the background of the original photograph weren’t intriguing enough, he swapped them out with the background from another old snapshot.

Preferring oils for their vibrant, deep, and sensual qualities, when Crow begins to paint, he intuitively selects a presiding color—such as the muted plum of the pavement in Chuck and Cindy or the very specific Naples Yellow of the sky in Enrique’s Cart.

“Executing the painting is figuring out what the conversation will be between the dominant color and the others. This conversation is something that I am rarely able to anticipate. When I’m really in the zone, the painting will start to tell me what colors it wants. That’s the magic of painting,” Crow said.

Because much of his time is defined by being a dad, Crow says that on weekdays, if he gets four or so hours in the studio, that’s a good day.

“I’ll spend the first hour fussing about. If you’ve ever watched a cat get ready for bed, I’m kind of like that in front of my easel. I wish I could just get to the studio and sit down and start to work, but I’ve learned that it takes a while to get into the right headspace. Inevitably, I’m just getting into the zone when I need to run home,” he said.

Crow says his path to becoming an artist has been a long and winding road. As a child, he loved drawing cartoons that continued well into his teen years.

“In high school, I drew a few cartoons that were so pointed, though not inappropriate, that I was dragged into the teachers’ lounge and yelled at. That, I thought at the time, was a successful cartoon,” he said.

In college, other disciplines dominated his interest, so it wasn’t until a merging of events aligned much later that he turned a corner.

“I got a couple of film degrees. Worked in Hollywood in varying capacities culminating with me working at Yahoo! Movies as a journalist. Then, within a couple of months in 2013, I got laid off, learned that my wife was pregnant, and fell back in love with art,” he said.

This new chapter sparked serendipitously in Santa Barbara when a friend invited him to participate in an all-night draw-a-thon hosted by a local museum.

“This was before fatherhood, so sleep deprivation was a novelty. Somewhere in the days before the event, I had a brainwave about drawing vice presidents and cephalopods, which I later called Veeptopus. It made me laugh, so I just went with it. That night, I banged out about 22 veeps, starting with John Adams and ending with Levi P. Morton,” Crow said.

The response to the drawings was so positive that Crow was encouraged to complete the series by drawing all 48 vice presidents. By the time he got to the end, he realized that his rusty drawing ability had improved from the exercise.

“My Joe Biden was notably better than my John Adams. Then, after doing them all again, I noticed I had again improved. I ended up redrawing all 47 vice presidents about three times. Except Al Gore. He was a real bitch to get right. I drew him five times before giving up and throwing a tentacle over his face,” Crow said.

The next step was selling prints of the series on Etsy, resulting in an astounding level of popularity. He also received a generous amount of press with articles in Boing Boing, The Huffington Post, and The New York Times. Eventually, Crow launched a Kickstarter campaign to successfully publish a book of the collection titled, Veeptopus.

By 2018, he hit another auspicious crossroad when he moved into a house with a spare bedroom where he was able to set up a home studio. At this stage, Crow admits to knowing next to nothing about oil painting, though it was something he’d always wanted to learn.

“So, with the hubris of someone who has no idea of what he’s doing, I started making bad paintings. I started to hit my stride in 2019. My technical ability—along with my understanding of color and composition—could almost keep up with my artistic vision,” he said.

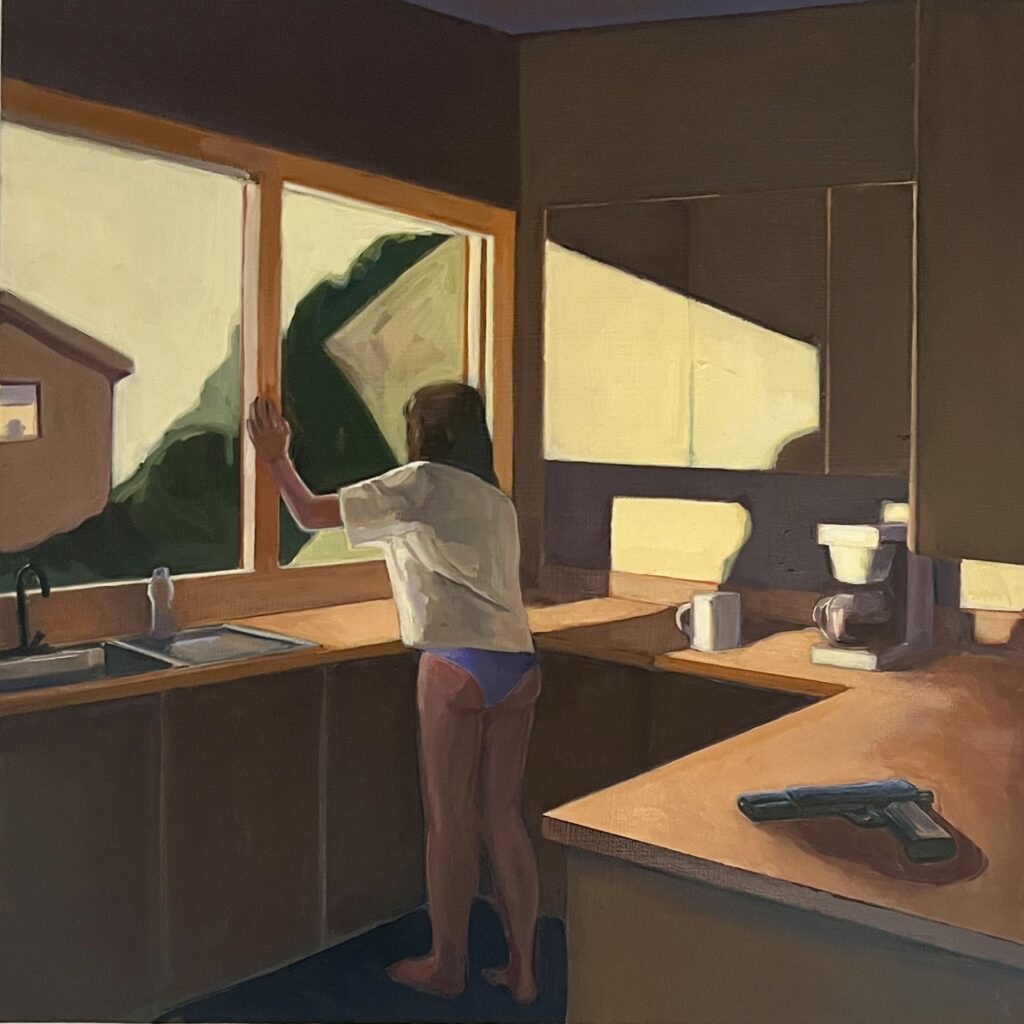

What Crow discovered in the days since those humble beginnings was that the subject he kept coming back to was that of the Californian suburb.

“When I was younger, I had a collection of boring postcards. There was something bleakly funny about going to the trouble of making a card celebrating something as unremarkable as a roadside rest stop or a squat, bunker-like motel. And that thing I found funny about those postcards also fascinates me with suburbs. That uncanny magic of the exceptionally unexceptional,” he said.

Crow said he struggled for a couple of years before stumbling onto that magic which has captivated him since. In using the suburbs as a stage for “quiet psychodramas”—bodies supine in cul-de-sacs, women in gardens staring off into space, and of course, ice cream carts abandoned by the kidnapped—Crow has found his rhythm.

“I don’t really understand where the ideas come from or what they mean, but my most successful paintings hold a magnetic power to me, as if I’ve tuned into some unconscious frequency of the times,” Crow said.

With a seemingly benign backdrop, Crow’s canvases lend themselves to easy commentary about current events from the pandemic to “America’s slide into fascism”—topics that have very much influenced his work. “What I’ve found, is that if you paint a rude picture of Trump, it dates very quickly. But if you manage to capture how it feels living under Trump, that work will have a power that tends to endure,” he said.

Crow worked furiously in preparation for his show at the Triton. He says, though there are a lot of walls to cover, he was excited to see his works nicely staged in one big room. Looking back over his career, Crow feels amazed that he has landed where he has, considering how in his so-called misspent youth he tried on so many different hats, from academic, video editor, journalist, screenwriter, to corporate drone, and none of them really fit.

“It didn’t occur to me that I could make a career out of what I really liked doing,” he said.

In the past year, Crow has been reading a great deal, mostly novels written in Germany in the 1930s or the Eastern Bloc during the Cold War, further fueling his work toward reflection on our precarious times. “It’s helped me get perspective on the stupefying changes happening to this country,” he said.

In turn, he hopes that people will have a reaction to what he is revealing in his work, even when it’s not exactly favorable. Last year, Crow had a painting in a large group show depicting a suburban pool with a figure floating face down (like William Holden at the beginning of Sunset Boulevard) that was placed front and center in the gallery space.

“An art patron, I later learned, hated, I mean, HATED the painting. She all but demanded that the painting be taken down, even returning to the gallery the next day with the same request. Clearly, this painting really made an impression on her. Of course, I’d much prefer that people would be positively affected by my work. I like validation. But I’d much rather hear that someone hated my work than to hear a tepid, it’s nice,” Crow said

When asked if he had anything further to share, artist Jonathan Crow joked wryly, “My father told me on my wedding day that you should never eat the liver of a polar bear because it has toxic levels of Vitamin D. I’ve always found that to be useful advice.”

Regarding his later-blooming career, Crow becomes more contemplative, finding its meaningful purpose inside a Nina Simone quote. “It goes something like, ‘An artist’s duty, as far as I’m concerned, is to reflect the times.’ That sums it up better than I could.”

For more information, visit his website jonathan-crow.com and on Instagram. Crow’s solo show, Cul-de-Sac is on view at the Triton Museum through May 3, with a reception on January 24.