Pop quiz: Which famous American writer said the following?: “I am an anti-imperialist. I am opposed to having the eagle put its talons on any other land.”

If you went with Gore Vidal or Noam Chomsky or W.E.B. Du Bois—well, good guesses. But the actual speaker was the guy who wrote The Adventures of Tom Sawyer—Samuel Langhorne Clemens, better known as Mark Twain.

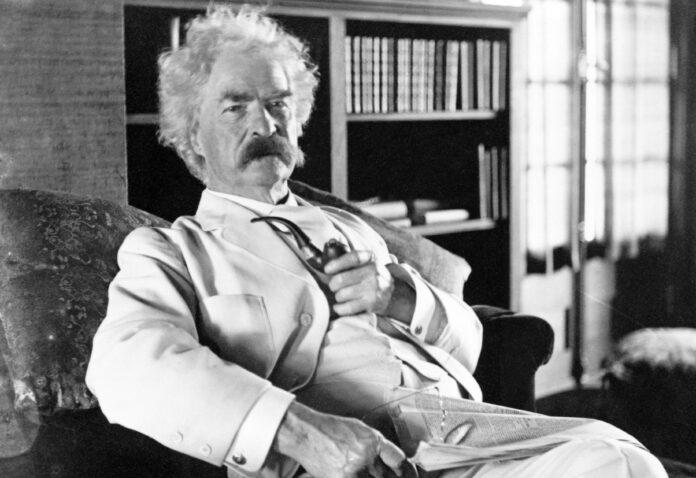

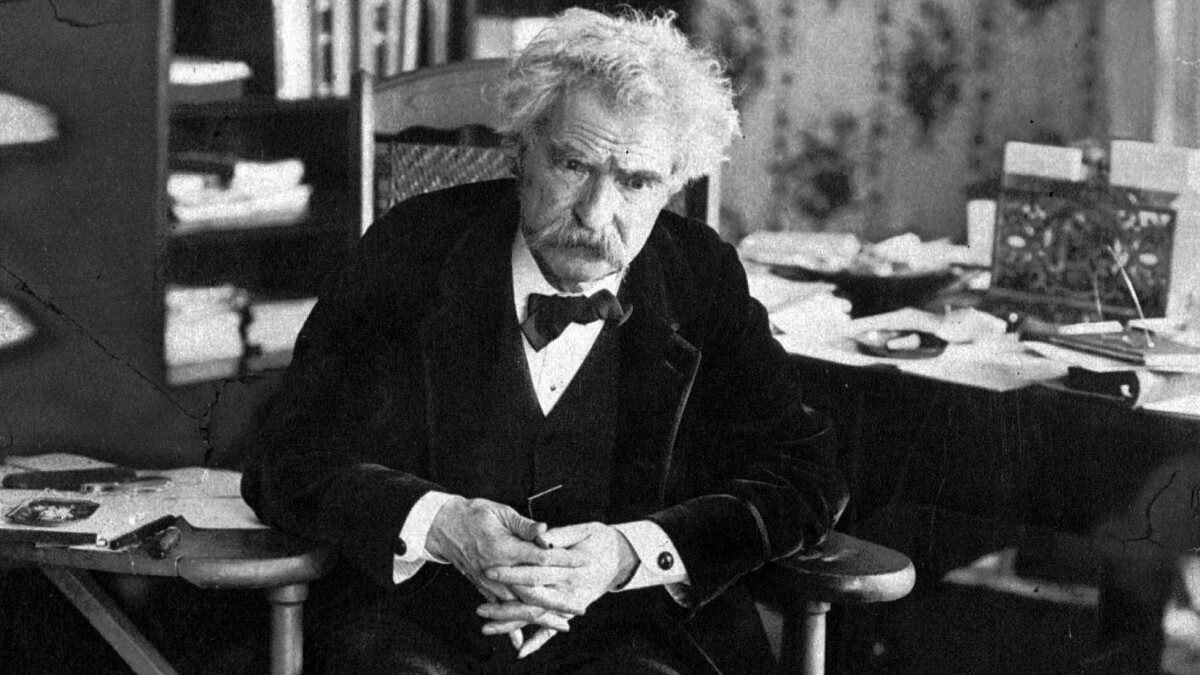

As is our standard hero treatment, the USA has turned Twain into a much warmer and cuddlier figure than he was in real life. We think of him as a humorist, a spinner of yarns about jumping frogs, and a teller of adventurous and moral tales of Tom Sawyer, Huck Finn, princes, and paupers. And he was those things—at times.

But in celebration of his birthday on November 30, I prefer to remember the Twain we’ve done our best to forget—the Twain who made our country uncomfortable, calling out US and European violence and aggression overseas. Anti-imperialist Twain could still be humorous, but this humor drew blood.

Sometimes, he dropped the humor entirely. Of Belgium’s King Leopold—who, by the early 1900s, had essentially turned what was then known as the Belgian Congo into the world’s largest slave-labor camp—Twain wrote, “In fourteen years Leopold has deliberately destroyed more lives than have suffered death on all the battlefields of this planet for the past thousand years … It is curious that the most advanced and most enlightened century of all the centuries the sun has looked upon should have the ghastly distinction of having produced this moldy and piety-mouthing hypocrite, this bloody monster whose mate is not findable in human history anywhere, and whose personality will surely shame hell itself when he arrives there—which will be soon, let us hope and trust.”

In 1905, Twain published “King Leopold’s Soliloquy,” in which he assumed the voice of the Belgian king, railing against his critics and wrapping his brutality in protestations of Christian faith. Twain’s Leopold speaks of his desire to “lift up those twenty-five millions of gentle and harmless blacks out of darkness into light, the light of our blessed Redeemer.” But then the pretense starts to drop as he rages at those who dared criticize him:

“They tell how I levy incredibly burdensome taxes upon the natives—taxes which are a pure theft; taxes which they must satisfy by gathering rubber under hard and constantly harder conditions, and by raising and furnishing food supplies gratis—and it all comes out that, when they fall short of their tasks through hunger, sickness, despair, and ceaseless and exhausting labor without rest, and forsake their homes and flee to the woods to escape punishment, my black soldiers, drawn from unfriendly tribes, and instigated and directed by my Belgians, hunt them down and butcher them and burn their villages—reserving some of the girls … But they never say, although they know it, that I have labored in the cause of religion at the same time and all the time, and have sent missionaries there (of a ‘convenient stripe,’ as they phrase it), to teach them the error of their ways and bring them to Him who is all mercy and love, and who is the sleepless guardian and friend of all who suffer.”

Before taking on King Leopold, Twain had already assailed the imperialism of the US and multiple European nations in “To the Person Sitting in Darkness,” published in 1901. Here, Twain directs his sarcasm at the notion that it was the “white man’s burden” to uplift the allegedly less-advanced races, using the voice of one supposedly involved in that cynical process to catalogue its excesses as being bad for business:

“Extending the Blessings of Civilization to our Brother who Sits in Darkness has been a good trade and has paid well, on the whole; and there is money in it yet, if carefully worked—but not enough, in my judgement, to make any considerable risk advisable. The People that Sit in Darkness are getting to be too scarce—too scarce and too shy. And such darkness as is now left is really of but an indifferent quality, and not dark enough for the game. The most of those People that Sit in Darkness have been furnished with more light than was good for them or profitable for us. We have been injudicious.”

Twain then proceeds to catalogue the brutalities inflicted on African and Asian people by Britain, Germany, Russia and other nations before turning his rhetorical guns on the United States and its occupation of the Philippines. This is history that my schooling entirely omitted. Twain finally taught it to me when I was in my forties, telling a story of betrayal and treachery that most Americans never learn:

“We knew they were fighting for their independence, and that they had been at it for two years. We knew they supposed that we also were fighting in their worthy cause—just as we had helped the Cubans fight for Cuban independence—and we allowed them to go on thinking so. Until Manila was ours and we could get along without them. Then we showed our hand … We forced a war [with the Filipinos], and we have been hunting America’s guest and ally through the woods and swamps ever since.”

After laying out the casualties we inflicted on our former allies, Twain sums up: “…we have turned against the weak and the friendless who trusted us; we have stamped out a just and intelligent and well-ordered republic; we have stabbed an ally in the back and slapped the face of a guest; we have bought a Shadow from an enemy that hadn’t it to sell; we have robbed a trusting friend of his land and his liberty; we have invited our clean young men to shoulder a discredited musket and do bandit’s work under a flag which bandits have been accustomed to fear, not to follow; we have debauched America’s honor and blackened her face before the world…”

This is brutal stuff, and Twain didn’t need to do any of it. At this point in his life he was a celebrity, as much so as any movie star or pop singer you could name today. He could have just basked in the glow of his successful books and speaking tours and enjoyed a quiet retirement, but instead he railed repeatedly against injustices committed by his own and other “civilized” governments.

Literary critics have mostly not been kind to these later writings, dismissing them as the rages of a man embittered by family tragedies (by this point Twain had outlived his wife and three of his children.) But there’s something gloriously unfettered in these works—I’m highlighting the anti-imperialist pieces here, but there’s also the scorching anti-war screed, “The War Prayer.” This is Mark Twain with the seatbelts unfastened and the parental controls set to “Don’t give a f***,” and it’s glorious.

Happy birthday, Mark. We sure could use you now.