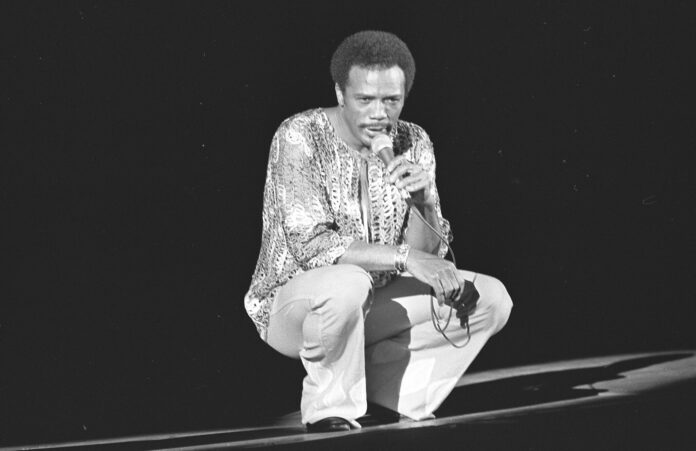

For more than seven decades, Quincy Delight Jones—master producer, composer, and entertainment titan—revolutionized culture through the prism of song. Men of his zeal, superproducers of his ilk, are not just old school; they are melded from a different education. That much higher-tempered steel involved sitting at the knee of Count Basie and Clark Terry, ears open and mouth shut while being informed on how Louis Armstrong created jazz, without samples or radio stations. Jones came from that era of verbal instruction, a tradition no longer in practice.

From a bygone era, this American maverick was the Apple Corporation before Apple was conceived. Using music to penetrate the entertainment industrial complex, he became a record producer and branched into film and television, scoring 40 films and hundreds of TV shows. During a time when Black Americans were not looked upon as managers or executives, he became vice president of Mercury Records in 1964.

“I started as an arranger first. That’s how I became a producer,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 2001. “It’s a path you go through as an arranger that opens up a lot of doors of understanding. You work with all kinds of different people from Dinah Washington and Billy Eckstine, Tony Bennett, Paul Simon, Sinatra, Aretha [Franklin], Sarah [Vaughan], Ella [Fitzgerald], and Carmen McRae. You learn so much from that school.

“That school doesn’t exist now, so it’s hard for them to understand what that gives you. Seven hundred miles a night for years. Traveling on that band bus. Seventy gigs in just the Carolinas. Twenty-seven in California. Everywhere. It’s ridiculous. And get stranded with a big band in Europe, and some sucker is gonna come talk to me about sellin’ out. Please. Give me a break. Yo mama!”

On Sunday, November 3, with his family surrounding him in his California home, Quincy Delight Jones passed away in his sleep at the ripe age of 91. One of the most nominated artists in Grammy Awards history, earning 80 nominations and 28 awards throughout his career, it’s hard to envision what 20th-century music at large would be without his ear and studio wizardry.

By founding Vibe magazine in 1992, he allowed the culture to cover the culture; Rolling Stone was out of their league attempting to cover hip-hop at the time. But Vibe also created a lane for black writers to maneuver through the magazine publishing industry and eventually reach the heights of writing for the New York Times, Washington Post, and Wall Street Journal. Q did that, along with shrinking larger-than-life egos so they all could fit into one recording studio for an all-star charity singles to fight famine in Africa, producing the film The Color Purple (which introduced the world to Oprah Winfrey’s acting talent), and corralling the executives at NBC so that a young Will Smith could take a swing at a failed Morris Day television project that would become the hit TV show “The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.”

This fearless titan, no matter what new corner of the industry he was revamping, always returned to his first love: music. His firm grasp on the immediacy it held never left him. Like a first look at a painting or seeing a movie for the first time, music always reminds us of our humanity. When they brought Eddie Van Halen in to play guitar on “Beat It” for Michael Jackson’s Thriller, Eddie asked him, “What do you want me to do?” and Quincy, without missing a beat, responded, “I want Eddie to do Eddie; that’s what I want.”

Here are four Quincy Jones records that stand out in the midst of what many believe was his exceptional period from 1969 to 1981. These records, all collaborative endeavors—something artists should keep in mind; great things happen when people collaborate—within a Mount Rushmore’s career. Feel free to disagree; Jones has a discography of 43 non-compilation albums in total. We just want to honor one of the coolest and most impactful cultural figures in American history by getting quiet and letting his music do the talking. According to Q, that’s what brings God into the room.

QUINCY JONES, WALKING IN SPACE (A&M/CTI RECORDS)

Coming 10 years before MJ’s 1979 Off The Wall album, Space is Q’s jazz fusion masterpiece where he grinds up David Axelrod’s baroque smoothness with that Count Basie, Sinatra, and Ray Charles intellect. With electronic verve on a Creed Taylor production (which means something else to record digger heads), this melding of jazz, soul, and pop features Valerie Simpson of Ashford & Simpson fame, Hubert Laws, Eric Gale on guitar, Fender Rhodes of Bob James (crate digger bell number two goes off), bassist Chuck Rainey, and drummer Bernard Purdie. It remains forever mod-sounding, with downtempo producers in the ’90s sampling bits to make a new genre unto itself. Quincy is just widening the lane.

THE BROTHERS JOHNSON, RIGHT ON TIME (A&M RECORDS)

The bass and guitar funk connection that is The Brothers Johnson, under the producing powers of Quincy, made them mainstream stars in the R&B field, but the Shuggie Otis cover, “Strawberry Letter #23,” put everybody in historical waters for making a funk ballad, territories only perfected by the Ohio Players in previous times, into a pop hit and then forever melded into the brains of cinematic junkies a la Quentin Tarantino’s Jackie Brown. Quincy Jones, for the win, again.

MICHAEL JACKSON, OFF THE WALL (EPIC RECORDS)

The first union between Jackson and Jones feels like creatively they are floating and have no particular destination to land on. Disco, funk, pop, soft rock, R&B—sleek, sheeny disco built for large rooms, not necessarily tinny radios; this is an experiment that went so positively,

Jackson, who is creatively unbound by Motown and his father and brothers, explores musically, probably for the first time in his life. This freedom would be a curse. MJ would be searching for this quality result for the rest of his career but would never find it.

Jones unloads his back pocket of phone numbers of LA’s and probably the world’s most talented musicians. Songwriters included Jackson, Heatwave’s Rod Temperton, Stevie Wonder, and Paul McCartney. “I Can’t Help It” (written by Stevie Wonder) is a jazz piece, states Jones in his autobiography.

Off the Wall is the masterpiece and sketch Jackson would draw from for the rest of his career, but that exploratory ethos would never return—even on the record-breaking Thriller.

Off the Wall felt like it was built for us. All the rest of MJ’s albums were searching for something so far off in the distance that even he could not reel it in.

QUINCY JONES, THE DUDE (A&M)

True story. One day I was walking home to The Mission down 18th in The Castro and I passed, I think, Toad Hall and heard “Betcha Wouldn’t Hurt Me” on a proper dancefloor system around 4:30 in the afternoon. Happy Hour SF time and the windows were open. I quickly realized I had never heard that song on a bass-driven sound system.

Jesus; the synth washes, cut up in delay, those guitar lines, those bass dips from Louis Johnson (of The Brothers Johnson), the attitudinally correct reading from vocalist Patti Austin.

Incredible.

The Dude, released in 1981, winner of three Grammys, I’m convinced this was Quincy’s capitalizing on the MJ magic dust from Off the Wall and calling up his supreme team: Stevie Wonder, Rod Temperton, Patti Austin, Herbie Hancock, and James Ingram, proving he was just as prolific as anyone 20 years his junior. ‘Cause he was.