Advice for visitors to the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco’s “Manet & Morisot” exhibition at the Legion of Honor (runs through March 1): Do not read a single word. Ignore every introductory panel, artwork label, and sectional essay attempting to explain who made what, when, where, and why. This preemptive suggestion—coming from a writer!—may be counterintuitive, but might prove valuable, especially for first-time visitors viewing the exhibit.

Instead of or at the very least before reading, invest time and visual attention to the art of Édouard Manet (1832–1883) and Berthe Morisot (1841–1895). A person might only benefit by pre-knowing these two remarkable, avant-garde 19th-century painters became colleagues and were influenced by shared experiences. Manet and Morisot held each other in equal regard and underwent similar struggles as each resisted the conventions of the era’s Impressionist art. A dual enthusiasm for mucking around with paint unites their distinctive works. And yet, for all their many commonalities, in their work’s reception and daily lives in Paris of the mid-to-late 1800s, Manet and Morisot existed in gender-differentiated realities.

Before delving into the particulars of Manet’s advantaged standing as a man and his thickly painted canvases, or the less-privileged Morisot’s more liberated brushwork in nuanced portraits and often, exhilarating landscapes painted outdoors, the visitor is advised to wander without words—or dates. Form a relationship with the visual world within which they revolved like two beacons of light, each illuminating the other.

Then, cycle through a second time. Learn that Morisot was not only the female founding member of the original Impressionist group—she was the only woman to exhibit with the group under her own name. Discovery continues: Morisot was Manet’s model in some of his paintings, but she, who became Manet’s sister-in-law after marrying his younger brother Eugène, never painted her elder peer. Another tidbit without explanation is that, although Morisot owned many of Manet’s paintings, he collected few of hers.

Even without reading the overly didactic texts that zero in on the topic of sexism and miss opportunity for greater depth, the exhibit’s roughly four dozen paintings form a fascinating timeline of each artist’s individual growth. Their efforts to achieve expressivity not through technique alone, but vigorous investigation of their materials and pursuit of the subject matter’s essential features, unites the work. Two vibrant personalties behind all the majestic artistry emerge, and prove inspiring.

The artwork was loaned by private collections and major art institutions including Musée d’Orsay in Paris, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the National Gallery in London, and Pasadena’s Norton Simon Art Foundation. Turning attention to the chronologically arranged artworks, visitors will (hopefully) decide on their own favorites—but a few pieces shine in this writer’s memory.

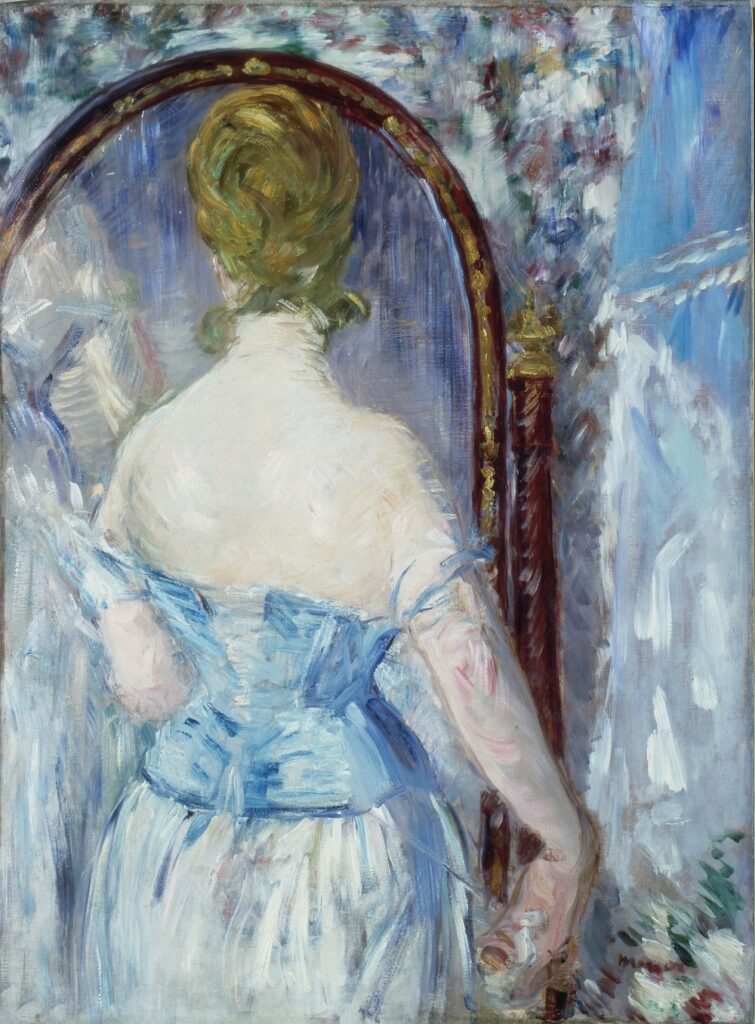

Side-by-side on one wall are Manet’s “Before the Mirror” (1877) and Morisot’s “Woman at Her Toilette” (1879-’80). The models in each painting are viewed from behind; the bare skin on their backs and exposed necks is alluring, sensual without any hint of sensationalism. Standing and seated, respectively, in front of mirrors, Manet’s figure is composed of brushstrokes that appear authoritarian and swiftly rendered; Morisot’s handling of the paint is less linear, with strokes that swirl and swoop ambiguously. Her woman appears simultaneously pinned in place and spun in a snowstorm of fabric, powder puffs, and patterned wallpaper.

While Manet’s skillful rendering burns on in memory, it is Morisot’s humanity that causes deeper reflection beyond the artist’s deft handling of the paint. Queries abound: Is the woman undressing or dressing? Is she content or consumed in regret, at the end or start of a day? Is she alone in the room, or is there an observer (other than us)? We want to know her, not just look at her admiringly.

Morisot’s “Interior” carries a similar degree of nuance and imagined storylines. A woman sits, seemingly lost in thought, kept company by an empty nearby chair. A girl stands amid soft drapery, looking out a window while attended by a maid, or governess, or family member. Images reflected in a mirror and an unframed painting propped behind the seated woman suggest either an art studio or a private domestic space. The painting could be seen as an expression of Morisot’s own life, in which boundaries between professional and personal spaces and identities were often blurred or non-existent.

Manet’s works in the exhibits are intriguing due to the lingering sense of isolation that emerges and lingers. The impression is partly attributable to his tendency to paint people standing alone or moving in small, separated clusters. Accompanying this compositional element is the coolness in his deliberate use of dense, black tones, which tend to undercut or reduce a work’s warmth. A third factor is the gaze of his figures. In “Interior at Arcachon,” two people seated on either side of a circular table, a glimpse of a coastal sea channel as a brilliant backdrop, do not engage with each other. Eyes averted, they exist in a shared space, seemingly unconnected.

Similar detachment can be found in Manet’s most-famous “The Balcony,” as well as “View of the 1867 Exposition Universelle.” His aggressive approach to portraiture is put to great and powerful use in “Berthe Morisot Reclining,” and “Morisot with Bouquet of Violets.”

Additional standouts among Morisot’s work—impossible to resist naming a few more—are “In a Villa by the Sea,” “Before the Mirror,” and “The Harbor at Lorient.” There is mystery within each painting, but also the distinct relatability of her people and places. Even across the intervening decades between the art’s creation and the present moment, the humanity of her work sings.

Ultimately, Manet and Morisot speak out from canvases and paper in a language composed of color, line, light, and shadow. Theirs is the language of the eyes, not of the tongue.

MANET & MORISOT runs through March 1. Legion of Honor, SF. Tickets and more info here.