Economic inequality, not zoning or “constraints” on construction, is responsible for the housing affordability crisis in the United States, a new academic study shows.

The study, by four leading urban scholars, directly contradicts the narrative that has been driving housing policy at the local, state, and federal level: that deregulating housing will increase affordability.

San Francisco is one of the cities the authors use as a case study, and their mathematical simulation suggests that is could take up to 100 years of increasing housing supply at levels that are unrealistic at best to see rents fall to the level where a worker without an advanced degree could afford.

“The simulation makes clear it is unrealistic to think that we can deregulate and build our way out of the affordability crisis with market-rate housing, even with large positive supply shocks, in any reasonable time frame,” the study states.

One of the lead authors is Michael Storper, a UCLA professor who has studied urban housing markets for years. He has argued that deregulation and upzoning could actually make gentrification and displacement worse.

The study doesn’t say that upzoning is a terrible idea; it might allow more people to live nearer where they work, reducing commute times and carbon emissions. What it won’t do, the authors say, is bring down housing prices in any significant way.

Under the right circumstances, well designed and executed upzoning may also reduce carbon emissions and improve urban amenities. But ironically, if these goals are achieved, increased access to jobs and amenities will make those same locations more expensive; they will not make desirable locations affordable to households facing onerous cost-burdens, and may in fact worsen their outcomes if policies are not sufficiently context-sensitive. Hence, while upzoning may be desirable from the standpoint of some policy objectives, it is not a robust tool to increase affordability

In fact, they argue, the deregulation strategy that is at the heart of the Yimby movement is popular because it’s easy for powerful forces in our society to accept:

Part of the appeal of the deregulationist narrative is that it suggests we can achieve affordability without major changes to labor market structure or significant public investment in the housing sector.

That’s the crux of their argument: The crisis in affordability is not linked to a lack of housing supply, but to the growing economic inequality in the country, particularly in cities like San Francisco.

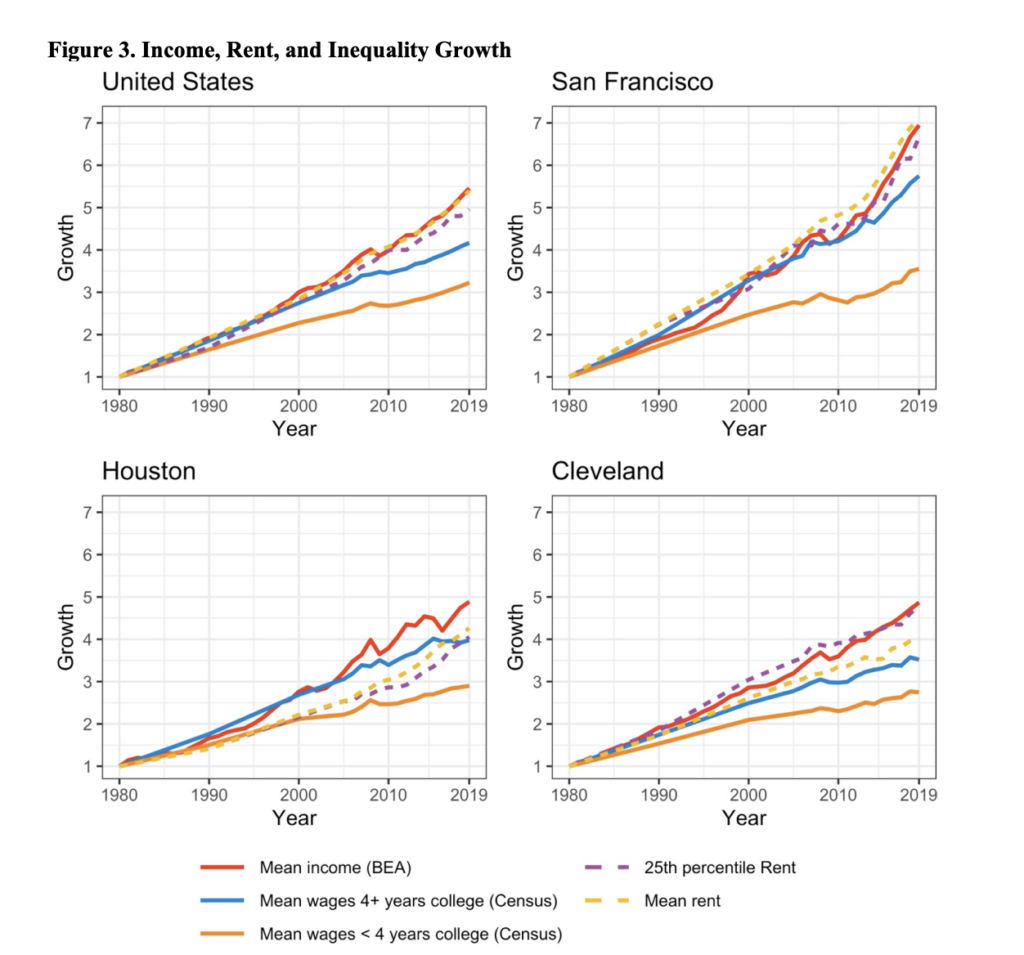

Following data from the National Bureau of Economic Research, Storper and his colleagues note that housing prices very closely track average incomes, even in cities like Houston, which has no zoning at all, and Cleveland, which has lost 100,000 residents since 1970.

Rather than regulation-induced supply restriction, today’s affordability crisis reflects fundamental transformation in the structure and geography of the American economy. The combination of rising national inequality and spatial sorting of economic activity has reshaped regional labor markets and incomes, producing divergent affordability outcomes. These shifts are evident across cities with widely varying regulatory environments and growth rates.

In San Francisco, where observers often lament regulation-induced supply restriction as the cause of the dramatic increase in housing costs—600 percent in mean rent over the 1980–2019 period—mean income has increased by the same amount. The affordability crisis is particularly dramatic in San Francisco because income inequality has widened much more than elsewhere. The wage incomes of the college educated grew 475 percent while those of the noncollege-educated grew 255 percent, more than double the national increase in inequality.

More:

The deregulationist view of our housing crisis, and the academic literature upon which it stands, fails to account for key conditions that structure today’s housing affordability crisis. It harkens back to a mid-20th century America in which housing was more affordable, but ignores how this period was marked by a fundamentally different distribution of income, and different spatial sorting patterns of people and jobs.

The study doesn’t address a key element of the mid-century economy: taxes. For most of that period, people with very high incomes paid very high marginal taxes, profoundly reducing economic inequality. If the top ten percent hadn’t been able to benefit from tax cuts that started with Reagan and never ended, the rest of us would have an additional $50 trillion (yet, trillion) dollars to spend—on housing, among other things.

In that period of housing affordability, when a person without a college degree could get a union job and afford to buy a house, most of the money people made (including rich people) was in the form of income—taxable income. Today, most rich people get their money from investments, stock options, and other sources that are often not taxed at all.

The study looks at the reality of housing construction, as opposed to the Yimby fantasy. Eliminating “constraints” is not going to lead to much more new housing, certainly not affordable housing, as long as the market is driven by for-profit developers:

Recent research on option value demonstrates that developers often delay construction in anticipation of higher future returns, particularly when they expect demand to grow. Ironically, regulations might actually increase housing supply if they reduce developers’ expectations about future profits, prompting them to build sooner rather than wait.

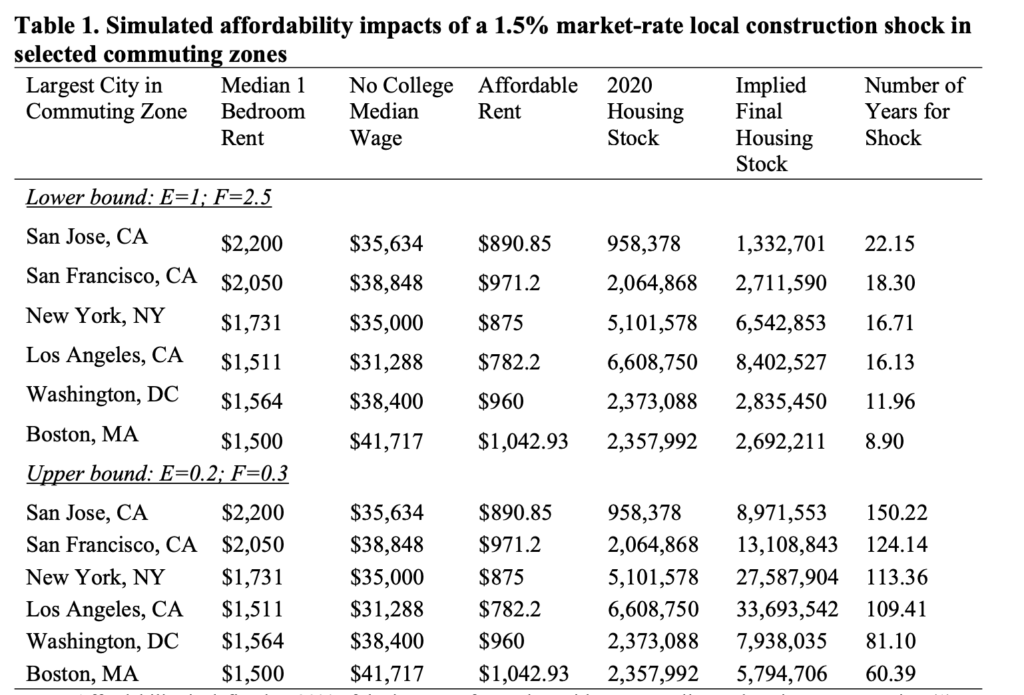

Then the authors looked a range of scenarios for what might happen to prices if, in a wildly optimistic world, developers built vastly more new housing in cities like San Francisco, what they describe as a “market shock.” We’re talking about tens of thousands of new units every year or two, more than the current infrastructure, including the labor market, could possibly support.

The answer: Rents might come down to the level that an average working-class San Franciscan could afford—in 20 years. But that scenario is almost impossible giving financing and land and construction costs; the more likely scenario is 100 years away.

Of course, when you are talking about those sorts of time frames, any kind of prediction is almost worthless. If the United States can’t address economic inequality in the next 20 (much less 100) years, the economy and society will become so unstable that housing prices will be the least of our problems.

If we as a society can’t come to our senses and realize, as Martin Luther King Jr. noted (in a comment that is largely missing from celebrations of MLK Day), that “we must recognize that we can’t solve our problem now until there is a radical redistribution of economic and political power,” we are wasting our time talking about upzoning and deregulating housing.

It’s just so easy to move around deck chairs on the Titanic.