mask4mask, 31, versatile. I tapped on the profile—the little cordoned off box on the left-hand side of my phone screen, one among a dozen other little cordoned off boxes—because, masculine normativity aside, I thought it was clever. It was the early era of the COVID-engendered quarantine and I was under the impression that in a few weeks’ time I would be back on the grind: scrolling, tapping, chatting, meeting. A little anticipation could be exciting.

At first I owned my reluctant celibacy (I’m just gonna do me!), and I found it enriching: to feel sexy outside of sex, to not have to admonish sexiness with penetration but have it stand on its own; to observe better the feelings and intuitions of human beings other than being touched; to avoid wearing sex as conversation; to understand better my ultimate drives outside of absent-minded encounters with strangers.

I focused on other things prevalent in my life: teaching my class; research and writing; organizing against unfair labor practices at the university I attend and work; protesting against police violence and their supposed monopoly on the use of legitimate force, their codified alibi of reacting to an “objectively reasonable” threat, and their “qualified immunity” from legal punishment. I filled my time with politics manifest—instead of getting some action, I was part of actions during a time that felt like a sea change for our country. This seemingly marked progress was more than enough excitement.

But when days merged into weeks, weeks into months, and months gave way to a quarter of a year, the anticipation yielded a yawning void. As the country was laying its inept, rigid racial and class structures—foundational, systematic, historic, contemporary—bare, and the world over was settling into a state of anxious complacency, I grew lonely, horny, desperate. And so I opened the apps again and decided to implement a two-tier screening system consisting of a couple of simple questions:

- Have you been socially distancing?

- Do you think #BLM?

For the most part, the responses served as sad reminders of the limits of the search for trustworthy, uninterested intimacy on the apps. One led to a Zoom date—consensus was made, a time was chosen, and the link was sent. We signed on, each having a coffee mug in our hands, the pandemic lifestyle allowing for these digital dates midday. The whole virtual date felt a bit forced. It ended a bit raunchy, but more because it went there immediately after the conversation ran dry. It was fun, but it made me miss the physical spaces—the cafes, bookshops, bars, clubs, parks—the spaces imbued with queerness, with the trace of us and the trace of those before us, of legacies.

I grew weary of the screens, of the digital meeting rooms. What even was I looking for in this pallid simulation of the world?

For the major part of my life I have been happy to be single, but there is something about this quarantine that makes me feel as if something is missing. But it isn’t a partner. The lack is a less obvious one, another type of intimacy that I found only in particular spaces. It is an intimacy that the digital plane feels devoid of, at best vying for mimicry. It was a sense of solidarity I felt in those physical spaces. The digitized versions—dance parties, happy hours, dates—felt like sad ventures at mimesis. Because somebody reduced to their screen is just not as real without the ability to garner their bearing—their body in relation to yours, their mind and their laughter and their smell in relation to yours.

And so I sought them out: real queer people. I walked and drove passed the shuttered bars with their messages of optimism scrawled upon the wooden boards. And as I cruised around in search of that intimacy I felt I had lost, I thought back at the queer history of our city and I tried to put into words the sentiment of those places providing for me shelter and teaching me unadulterated acceptance.

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

I thought about the legendary spaces scattered about—from the Tenderloin to the Castro, SOMA to Polk Gulch—each their own queer enclave built upon and containing histories of uprising, of riots, of pride, of deviance, of solidarity. We became politicized in those spaces before we could name all the ways in which we were beautiful. They were radical spaces once, where we stirred up good trouble in acts of survival, for recognition, through hard-won joy. And like so many of the places where white gay male idealism dominates, the digital spaces were devoid of a queer politics.

This is why, when The Stud—the over 55-year-old, cooperatively-owned queer bar and nightclub fighting off the ubiquitous neoliberalizing forces in the South of Market (SOMA) district, on that lonely corner of Ninth and Harrison Streets—announced it was shutting its doors, I drove down to pay homage to the space. And when I arrived there were others outside, too, snapping photos, celebrating, remembering how that place made us feel. We greeted one another and exchanged memories from a safe distance, bridging even that with our mournful laughter. If those walls and stalls could talk. For a brief moment, under the big lit-up arrow sign above the entryway kept burning through that last night, it felt as if our joy was a radical act.

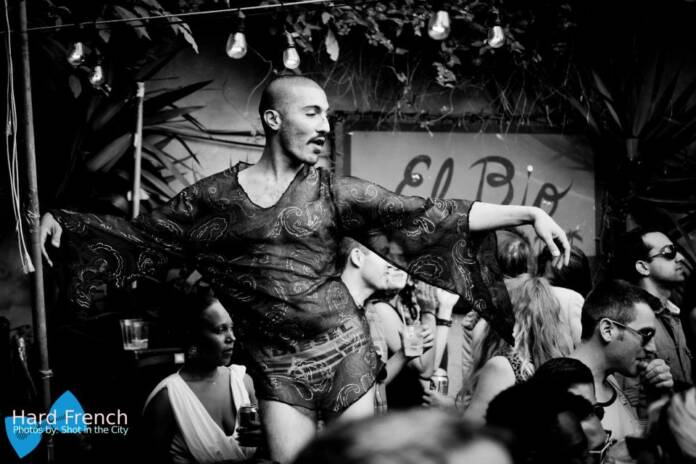

And so I continued my tour of the unpopulated queer places, driving to another bar, in the southern part of the city: El Rio. As I stood out front I imagined beyond its façade and I thought about how I would describe the place to somebody who had never been, as if to ascribe it a history, to populate it with words: Maybe I would tell them about the infamous $2 Tecate cans. Or the supersize Chiquita lady. Or the BBQ grill offering up burgers. Or the janky urinals where the lowlives (like myself) cruise. Or the coveted little palm-tree-shaded nook in the back patio. Or the busted karaoke machine at the end of the bar. Or the tight-but-always-right-fit photobooth. Or all the queer bodies, of color, dancing, free. Or maybe I would describe to them that entrance and its Dutch door swinging open as if to say: “Everyone Welcome. Your Dive.”

In spaces like these the future seems vast and full of possibility with every writhing body, every conversation an entire history. All at once there’s a pulse, a rhythm, a spectacle, and solace. It refuels and it allows us to avoid anxiety from all that precedes and proceeds. It is reason alone to fight. For the “leave it all there on the dancefloor nights.” For the nightly parade: the QPOC, the gays, the genderqueers, the lesbos, the drag queens and kings, the butch, the femmes, the high femmes, the queens, the fags, the non-binary people, the kinksters, the trans folx, the hoes, the polyamorous, the bisexuals, the leather daddies, the two spirits, the bears, the label-less, etc. etc.

Because in the end it was always about community, and about being with each other as a collective. A party—and party to something bigger, a sense of being singular but social. And so for a moment the world aflame fades away, a respite. But you don’t ignore it, you use it to expel it through your energy. And it doesn’t solve much pragmatically, but it reinstates you.

So that when you leave, finding your footing at the door, you are assured that you’ve still some fight left in you.

Talib Jabbar is a born-and-raised San Franciscan navigating the hard, good life. He is a doctoral candidate in literature and critical race and ethnic studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz.