A quartet of windows hangs from the ceiling within a small storefront on Kearny Street. Framed in potent greens, reds, and yellows, assorted objects and transparent images are embedded within the clear panes of each half-moon form. This curious collection of small plastic objects, textiles, and organic material beckons the viewer to enter the gallery and get a closer look.

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman’s exhibition at Friends Indeed Gallery, “Here Be Dragons” (through March 25), explores histories of colonial economies, mythologies, and systems of power, visualized through symbolic objects. Situated behind floor-to-ceiling glass at street level, the exhibition is visible even when the gallery is closed. However, with no text to announce its presence as an exhibition, passersby might puzzle over the intended purpose of these suspended windows. This ambiance of questions is a foundation of the exhibition.

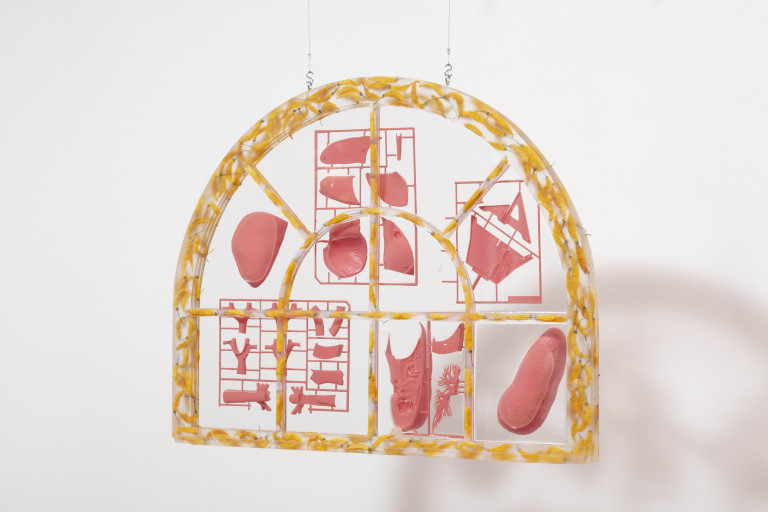

Bermúdez-Silverman’s sculptures reveal slippages in surface perception. What is at first thought to be painted wood and clear glass is instead entirely epoxy resin, cast from a mold of a semi-circular window frame. The vibrant hues of each frame are not from paint or dye. Organic material embedded within the resin frames create the colors: ground red pepper, lemon drop peppers, moss. Bermúdez-Silverman unseats the form and function of the original window shape, and thereby echoes an unsettling of the architecture of dominant histories.

In the exhibition’s center, a lunette is filled with grains of ground red pepper, resulting in a striking vermillion tone. The window panes enclose a varied group of objects: a twist of tobacco, a pearl oyster shell, a red ant made of glass, a cayenne pepper. This seemingly discordant assortment of objects, placed in relation to each other, form a visual language of colonialism’s extractive economies and invasions of indigenous communities.

The title signaling commodities trade, A Pigeon for a Needle, a Turtle-Dove for One Glass Bead, a Pheasant for Two, and a Turkey for Four, comes from a sixteenth-century text by Spanish historian Francisco López de Gómara on the subject of Columbian pearl trade. Pearls, formed from irritants that disrupt an oyster, can be read in parallel with colonialist systems. Once deemed to be a global commodity, the harvesting of pearls transformed from indigenous practices to an extractive economy. Pearls can also be read as a paradox. Though they arise from an invasion, the oyster’s formation of this protective object also evokes the resilient creation of beauty against oppression.

Bermúdez-Silverman’s work is grounded in deep research into the histories and contexts of the material within each sculpture. However, rather than directly sharing an object’s significance, viewers are invited to dive deeper through their own curiosities. Bermúdez-Silverman crafts provocations towards inquiry, windows for viewers to experience research as one of the exhibition’s core materials. An artwork’s materials list, for example, becomes a springboard for further investigation, listing items like freshwater pearls, honey bees, and two varieties of pepper. What role did honey bees play within colonialist histories? How did varieties of pepper transit throughout the world, and who profited from this trade? As much as these sculptures are striking visual objects, their more powerful draw is in the questions they provoke.

Another lunette is framed with bright yellow peppers suspended in clear resin. Its title, “Qillu Uchu,” references the pepper’s indigeneity to Peru. A puzzling array of fleshy-pink plastic rounded shapes sit within the resin window panes, many of which linked together with thin tubes made of the same plastic. Peeking behind the window shows these objects protruding from the resin, both escaping the confines of the resin and trapped within it. They are pieces used to build an anatomical model of a lung. This work, at once the most abstract within the show, is also the most viscerally connected to the body. One can almost feel the peppers’ heat traveling through the body, warming every organ.

Here Be Dragons also foregrounds the practice of Western knowledge systems that framed indigenous peoples and societies as a fearsome other. The exhibition’s title refers to a Latin phrase signifying the exploration of unknown territories as venturing into mortal peril. Medieval Eurocentric cartography visually signified parts of the world unfamiliar to them as dangerous through the illustration of dragons and other fantastical monsters in these so-called uncharted lands. These belief systems became embedded in Western psyche, reinforced by colonialist explorers relaying back these denigrating fantasies as falsely witnessed fact.

In three of the sculptures, the transparent imagery is sourced from Ulisse Aldrovandi, a sixteenth-century Italian naturalist. Aldrovandi’s collection of illustrations that “documented” the history of monsters in the human and animal world became a frame through which colonialist invaders framed their encounters with indigenous communities. Cloaked under the guise of scientific thought (though entirely fictionalized), images and texts depicting indigenous peoples as monstrous and inhuman is an outright act of violence and active erasure of the breadths of indigenous knowledge. In an insightful text accompanying the exhibition, Elena Gross writes that “the authority of science has often been used to rationalize cruelty. The power of the myth itself can supersede humanity.”

Bermúdez-Silverman’s visually stunning windows emphasize the power held within active, enduring learning beyond surface-level. The artist’s material gestures invite a critical dialogue both with the artwork and within the viewer’s own present understandings. Encounters with these sculptures spark an unraveling research impulse that will continue to challenge assumptions, blind spots, and dominant narratives far beyond the gallery walls.

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman: Here Be Dragons runs through March 25 at Friends Indeed gallery, SF. More info here.