There’s a hush to Christine Elfman’s work, a soft silence that resembles a single beam of light shining into a cave. It is the kind of quiet that slows time, where seconds feel like centuries in the most beguiling way. In All solid shapes dissolve in light, Elfman’s first solo exhibition of photographic works at EUQINOM Gallery (through April 30), the process of creation is also quite slow. Many of the photographs were made using month-long exposures, an exceptional exercise in patience and care.

Anchoring the main gallery is a salon-style installation of seven works in grey and pale violet hues. Hands emerge from folds of dark fabric in Reproduction II, Variation II and Reproduction I, Variation II. The entwined hands gently fold over each other in a repetitive circularity. They also seem to bear a striking similarity. A closer look reveals that several are plaster reproductions; in fact, these are casts of Elfman’s hands and her mother’s. The intertwining of these living and sculptural limbs encapsulates the temporal and sensory dualities within All solid shapes dissolve in light. Dynamics between permanence and ephemerality are at the core of the exhibition.

These works, and several throughout the exhibition, are anthotypes: a nineteenth-century photographic process that uses materials from plants to create light-sensitive surfaces. A print’s color is determined by the botanicals used to make the emulsion. Elfman uses lichen for her anthotypes, resulting in their ethereal lavenders. To create the image, objects or image transparencies are placed atop the surface in a contact-printing method. Exposure to sunlight bleaches the pigment in uncovered parts of the paper, resulting in an image.

In Cloth Water Stone I, Variation I, ridges and folds of a surface cascade downward, as if a waterfall or draped cloth. It is unclear, as the title suggests, whether the form is liquid or solid. The material ambiguity in this work and others provokes an examination of the similarities between these forms. How might stone, water, and cloth be connected, to somehow all appear as the other? Rocks, for example, appear quite unchanging—but stone and earth are highly mutable in the scope of geologic time.

Water is one cause of this change, eroding rock over centuries. The dance between fixity and transformation wends through Elfman’s work, a reminder of what Octavia Butler wrote in Parable of the Sower: “All that you touch / You Change. / All that you Change / Changes you. / The only lasting truth / Is Change.”

Photography, from its earliest days, has been a medium of preservation, concerned with holding on in perpetuity. Elfman writes: “We photograph to define, hold, capture things… Early photographers were obsessed with fixing the image, so it would last forever. Yet experience shows us that the more you try to hold something still, the more it’s ruined.” The anthotype is related in history and technique to the cyanotype, a more commonly known process that also uses sunlight to produce the iconic blue-toned prints.

Unlike the cyanotype, however, the anthotype lacks image permanence under continual exposure to light. In other words, the anthotype will fade over time. This dance between fixity and ephemerality is core to Elfman’s material gestures in this exhibition, working with a process that eludes the permanence so associated with the photographic image.

A small fragment of a leaf is imprinted into stone in the diptych Fossil, Beech Leaf (diptych), Variation 1. On the right is a lichen-dye anthotype, and on the left is a digital print that uses archival inks and lichen dye. The fossil, a preservation of ancient organic material, often only contains the impression of something after the original being has long since decomposed. This work, presenting the anthotype that eventually fades away and the pigment print that is far more archival, underscores the dichotomy of the fossil. Some preserve the body of flora or fauna, and other contain their ghost. A fossil embodies both permanence and decay.

Elfman coated these anthotypes in resin, which extends the lifespan of the prints but not indefinitely. It is a gesture towards fossilization. And, like in many fossils, the anthotype’s organic pigment is not guaranteed to last forever. These images are quite alive: in a perpetual process of change, albeit happening quite slowly and even imperceptibly. However, even with the resin coating, they will elude preservation and eventually fade away in the light.

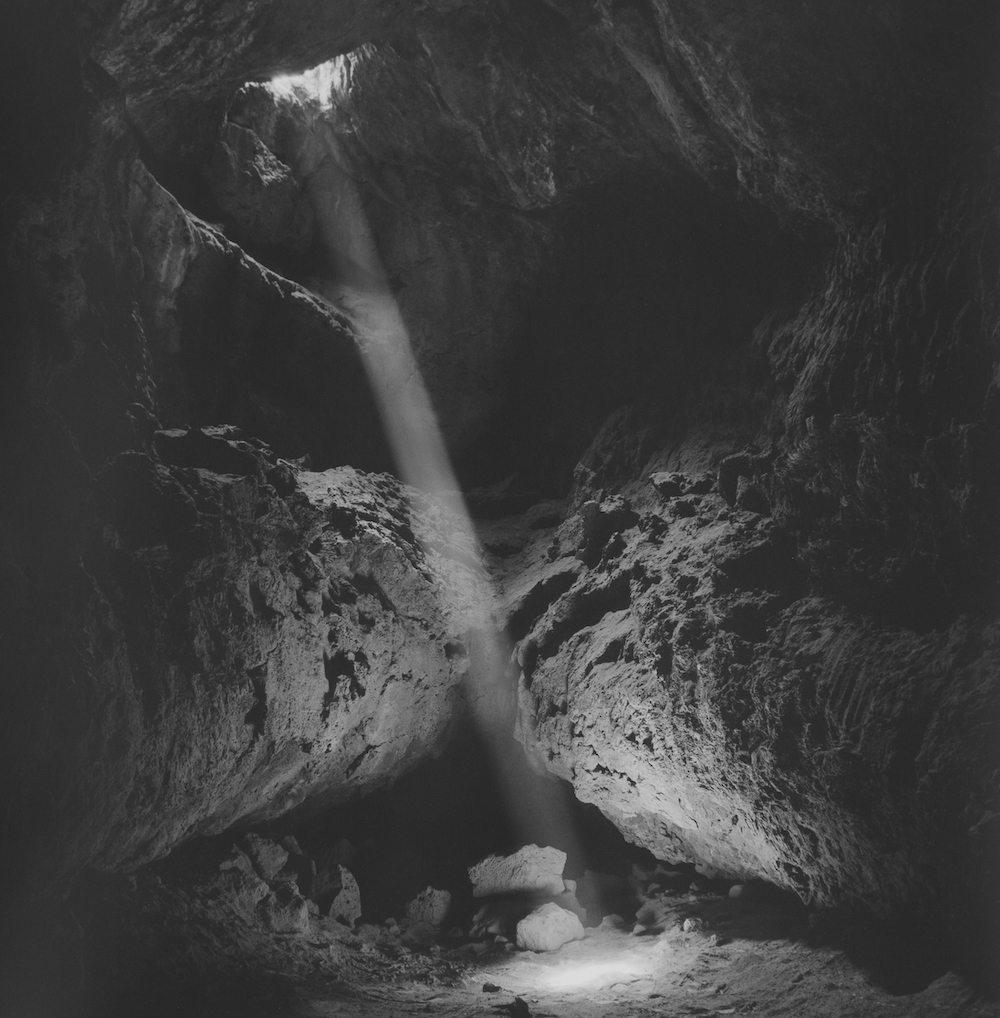

The exhibition also includes photographic methods that are more fixed, like the gelatin silver process (more commonly understood as photographs made in the black-and-white darkroom). In one of these works, Cave II, a stream of sunlight falls onto dirt and rocks in a cave. Light is fundamental to the existence of photography, an alchemical material that imprints a latent image onto film and paper (or causes an image to fade). Light is, as the exhibition title and anthotype process reminds, a force of change.

It is also ephemeral, impossible to hold with our hands. Photography, on the other hand, can preserve the presence of light and transform it into a physical object. Using the gelatin silver process to image light in Cave II, Elfman again enters the slippery and cyclical space between the momentary and the eternal.

All solid shapes dissolve in light is an exhibition that encourages slowing down, a particularly potent reminder as life “returns to normal” to an oft-frenetic pace. Change is happening all around us, but so is stillness. Take a breath to observe an anthotype before it fades away. Pause to perceive the millennia of lives that the land has lived before any of us were here, and the lives it will live after we are gone.

‘All solid shapes dissolve in light’ runs through April 30 at EUQINOM Gallery, SF. More info here.