With the Supreme Court having recently thrown Affirmative Action onto the ropes, it’s looking more than ever like the Jim Crow era we’d theoretically left behind long ago is primed for a comeback—if it ever fully went away. Two new sports-themed documentaries look at different fields of play that fought a long battle towards integration, or are still fighting it.

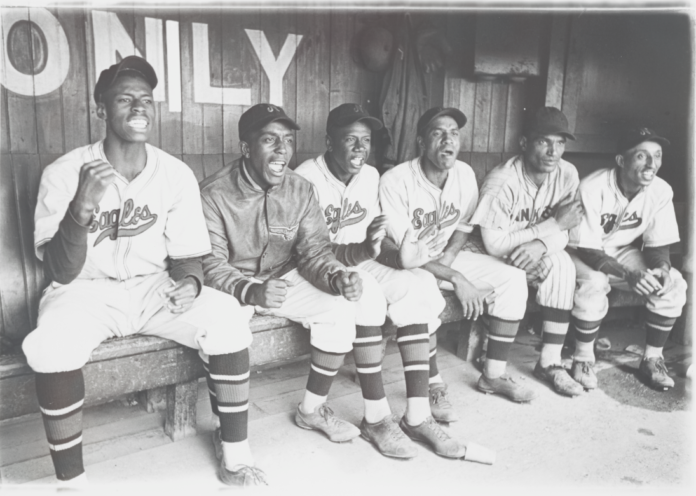

Sam Pollard’s The League chronicles the various all-Black baseball leagues that flourished for a few decades, including the Negro National. In actuality, a handful of African American players had played on pro teams as early as 1884. But within a few years, owners heeded the protests of a few racist voices and shut non-whites out entirely.

The original Jim Crow court decisions, with their alleged “separate but equal” justifications, both capped broader minority progress in society and encouraged self-contained cultural and economic development: Black-owned businesses, media, performing arts, and sports teams, much fueled by the Great Migration to northern cities. The disillusioning experiences of so many Black soldiers returning from WW1 (and then WW2) service, only to find themselves still second-class citizens, further drove a desire to “close ranks and build our own institutions,” as it’s put here.

Rich in archival footage and interviews (as well as commentary from latterday experts), The League charts glory days when players who might be as famous as Babe Ruth or Hank Aaron today—if they’d ever been able to play “the majors”—set records on teams like the Chicago American Giants to packed crowds dressed in their Sunday best. Yet their pay was pitiful and accommodations worse. It was only when some traveled to play off-season in places like Cuba, Mexico, and the Dominican Republic that they glimpsed how sportsmen of their ability, but different skin color, were typically treated. These teams had their own World Series, and inevitably word of their skills reached the ears of a mainstream that had pointedly excluded them for so long.

Jackie Robinson’s signing to the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947 was on the one hand an indisputable landmark in “breaking the color line.” On the other, it sounded the death knell for the Negro Leagues, with fit compensation for the teams who lost prize players seldom offered. A huge source of community pride, and profit, was largely lost in exchange for the upward mobility of integration—which of course left many behind in inner cities soon deteriorating from the postwar exodus to suburbia. This is a rousing story of an oft-overlooked chapter in US athletics, but it’s also one with a bittersweet “happy ending.” The League already played a limited three-day Bay Area run at AMC theaters last week, but is available via On Demand platforms this Fri/14.

The institutionalized discrimination that necessitated the Negro Leagues’ founding a century ago or more is unfortunately still alive and well, if operating in somewhat subtler fashion, according to Hubert Davis’ Black Ice. (It too is opening at AMC theaters Metreon, Mercado and Bay Street for a limited run, as of Fri/14.) It centers on the traditionally highest-profile sport in Canada—a nation that likes to think “real” racism is something that happens down south, in “the States.” But as various participants and observers testify, that is something of a national blind spot, not necessarily reflective of reality.

In some ways, this puck saga parallels the baseball one above. Overlaps include the past existence of a Colored Hockey League (partly populated by runaway slaves who’d gotten here via the Underground Railroad, or their descendants), and the offensively lowballed offers that non-white players often received when asked to join pro teams. Alas, much of what’s in Black Ice isn’t a matter of historical record, but is very recent, or even current. It wasn’t until 2019 that player Akim Aliu openly accused a coach of racist language and abuse—things many others then admitted they’d been encouraged to simply “put up with,” from teammates, opposing players, and spectators alike.

The Trumpian amplification of such hateful rhetoric as “free speech” is hardly limited to the US these days. Many interviewed here report routinely being greeted by the “n-word,” “monkey chants,” thrown bananas, and other forms of bigoted heckling. Official pushback to such acts tends to be weak, and even now the NHL seems to be dragging its feet on diversity issues. Black Ice could have used some or any input from the offending parties, assuming anyone could be found dumb enough to open their yap on the subject. But if this isn’t nonfiction storytelling as engrossing as The League, it still provides vivid evidence of a toxic culture within a sport that some non-white people can’t help loving—or being very, very good at—anyway.

Survival is the only game being played in several new thrillers:

Final Cut

Though certainly one of the more successful French imports in recent decades, Michel Hazanavicius’ 2011 silent-film homage The Artist was probably one of the least-seen Best Picture Oscar winners ever—which is not to say it was undeserving of that prize. Still, it’s surprising that the writer-director and star Jean Dujardin (who won Best Actor) have had such relatively low-profile careers since. That mystery is not clarified by Hazanavicius’ latest project, which sneaks into town at the Metreon this Fri/14. It’s an unnecessary remake of 2017’s low-budget Japanese zomcom One Cut of the Dead, a clever Rube Goldbergian construct I found just amusing, though others pronounced it near-brilliant.

Hazanavicius puts his own spin on the material while keeping its basic bones—perhaps a little too faithfully. Romain Duris plays a director whose work-ethic motto is “fast, cheap and decent,” who on that basis is hired to do a French remake of a Japanese zombie film. He’s unhappy to discover they won’t let him alter the very culturally-specific original script, then appalled when told the production will be a live-streamed half hour captured in a single shot—a technical stunt that would be near-impossible even if allowed multiple takes. Needless to say, everything goes wrong, exacerbated by cast members’ drinking, back issues, prima donna behavior, and more.

Final Cut means to be the Noises Off! of DIY genre filmmaking, but it lacks precision—the director and his collaborators (including spouse/frequent star Berenice Bejo) mostly seem to be just goofing off. To an extent, it’s fun watching them have fun. But at nearly two hours, the joke wears thin, and what seemed moderately ingenious in the Japanese version grows slapdash here, lacking any real point. It’s not bad, but these people should be capable of much better.

Mother Nature: She’ll kill ya, by ‘Flood’ or ‘Quicksand’

Two new streaming movies offer the kinds of entertainment value best served by being attached to a drinking game—sober watching is not advised. In Brandon Slagle’s The Flood (arriving in limited theaters as well as On Demand and digital platforms Fri/14), a hurricane forces high-security convicts in transit to be waylaid at a small police station ill-equipped to handle either them or the rising waters.

Worse, some heavily armed criminal colleagues show up to liberate and/or kidnap not-so-bad-guy prisoner Casper Von Dien, putting ponytailed blonde sheriff Nicky Whelan (who naturally gets stripped down to a wet tank top right quick) in an even tighter spot. But that’s nothing: All concerned are soon at risk of being gator snacks, as humungous reptiles slither into the facility through various pipes and grates. This knucklehead action movie with subpar FX lacks conviction, or even much sense of fun, unless you’re prone to har-de-har over a parade of painfully on-the-nose lines like “That was one big sumbitch!”

Still, it’s arguably preferable to Andres Betran’s Quicksand, debuting the same day on streaming services Shudder and AMC+. Carolina Gaitan and Allan Hawco play a newly separated couple forced to travel to a conference in Colombia, where they improbably decide between arguments to go on a hike together. You can guess what happens. I find quicksand a terrifying idea, but it’s pretty boring here—particularly since we care so little about the fates of two characters who seemingly can’t stop their marital squabbling for five seconds, even (or especially) when their very lives are at stake.

Parenting Problems: More ‘Bird Box,’ creepy ‘Rabbit’

Spanish brothers’ Alex and David Pastor’s Bird Box Barcelona is a sequel (or rather “parallel story”) to the 2018 Netflix hit that had Sandra Bullock trying to survive a mystery contagion inducing violent suicides worldwide. Caught in that same onslaught and subsequent societal collapse several thousand miles away is Sebastian (Mario Cajas) and young daughter Anna (Alejandra Howard). But we soon realize neither are quite what they appear to be, and that the characters in greatest danger may well be ones (including Barbarian’s Georgina Campbell) whose paths they cross.

This followup is impressive in physical scale, with some splashy sequences of violent peril in a city turned dystopian nightmare. But it errs in giving us protagonists we don’t root for. It also teases more explanatory intel on the unseen, possibly space-alien forces that drive people mad… without actually coughing up any. The original wasn’t great, but it was intriguing and involving; Barcelona ultimately saps one’s interest in further extension of the franchise. It launches on Netflix this Fri/14.

More rewarding is another, more low-key suspense film recently added to Netflix. Daina Reid’s Austrailian Run Rabbit Run stars Sarah Snook as a fertility doctor celebrating daughter Mia’s (Lily LaTorre) seventh birthday. But the child keeps acting more and more strangely, the mother more hysterically, until we wonder what the real issue here is: Hereditary insanity? Bad Seed-like malevolence? A supernatural possession? Hannah Kent’s script keeps us guessing to the end, and the atmospherically tricksy story is much enhanced by juvenile thespian LaTorre’s precociously eerie performance.