Growing up in the Delta town of Greenwood, Mississippi, artist Stephen Mangum says he has always been aware of the prevalence of racism in this country, a subject that has become the primary narrative of his paintings. Though he has lived in various regions, observations from his formative years in the South are never far out of reach.

As a child bounded by the hotbed of social activism and its reactive violence in the 1960s, Mangum codified his observations in the recent series, Illusions of My Childhood, by addressing white entitlement. Born in 1954, Mangum lived adjacent to the murders of both Emmett Till and Medgar Evers in Mississippi. He was a teenager when Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in Memphis and it was at this time that Mangum became acutely aware of the violent nature of the racism that roiled inside a pressure cooker, while the privileged class thrived inside a protective cocoon.

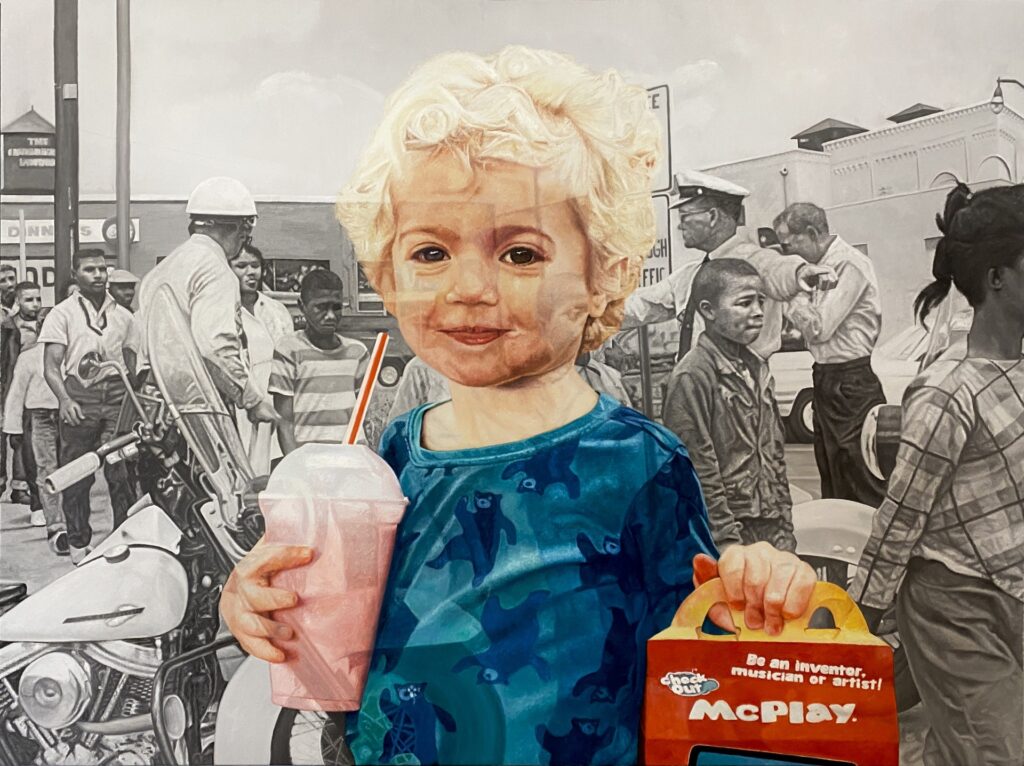

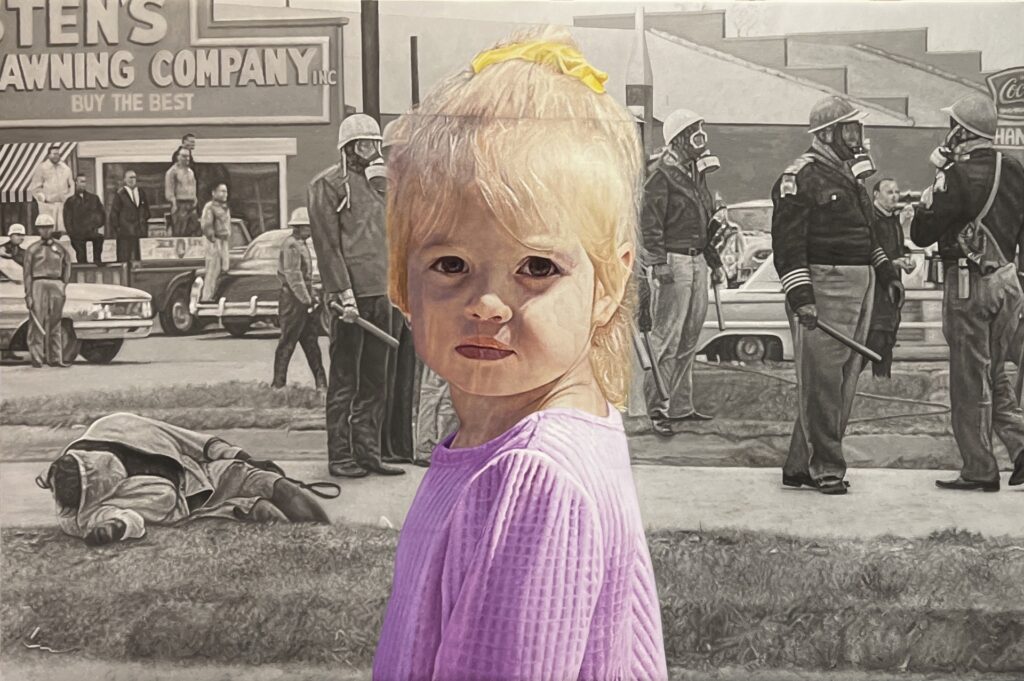

The 12-painting series was presented in a solo exhibition at the Rosa Parks Museum of Troy University in Montgomery, Alabama last year and took four years to complete. In this series of works, Mangum first creates a backdrop of black and white imagery of brutal scenes from the Civil Rights Era, based on photojournalism accounts of that time. He then paints images of young children (based on his own grandchildren) engaged in typical idyllic activities like eating an ice cream cone or holding a lollipop.

Mangum paints the children with a technique that allows just enough transparency to suggest that “the past permeates the present.” Innocence and hostility share space on each canvas, beckoning a deeper look at the persistence of hatred in our country and the imbalance within ongoing, unjust societal constructs.

“I think of my art as a means of communicating, my paintings tell stories. My work is inspired by the challenges of humanity and particularly the ideals of truth, love, and equity. Regarding the particular focus on racial inequality—well, growing up in Mississippi in the 1960s, this subject matter is part of my DNA,” Mangum told 48hills.

He considers his work confrontational, yet compassionate and hopeful. In a contemporary realist method of painting, Mangum draws us in with a provocative layering of images that illustrate how injustices coexist with contentment right under our noses. The veneer of the unaware attempts to colorfully cover up a starker background truth—the tumult of violence unseen by those with privilege enough not to have to witness it.

Mangum attended Washington & Lee University in Lexington, Virginia (BS cum laude, 1977) and has lived in Washington, D.C., New York City, and Fort Worth, Texas. Having lived in San Francisco from 1999 to 2003, he moved to Hong Kong for ten years before returning to San Francisco in 2013 to complete a BFA with honors at the San Francisco Art Institute in 2016. Currently residing in the Pacific Heights neighborhood of San Francisco, the artist says he loves the abundance of activities available in the city, the museums, the diversity, the liberal thought, and the climate.

Mangum has worked from a large studio space at the Industrial Center Building (ICB) in Sausalito’s historic Marinship district for nearly eight years. The building, which dates back to 1942, was originally designed to support the wartime naval effort and was transformed into a dedicated art space in the 1950s. It currently houses over 100 artist studios. Mangum usually works Monday through Friday in his studio, arriving in the morning with a plan and goals for the day.

“I jump in and start putting paint down immediately and don’t come up for air for several hours. I end each day by cleaning my brushes and then taking photos of the work in progress, which I study at home to identify corrections that need to be made in preparation for the next day,” he said.

Working in oils on linen, Mangum approaches painting as problem solving and visualizes the effect and/or result he is after without necessarily knowing in advance just how he is going to achieve it. His paintings are large scale (up to approximately six by thirteen feet) and, while they contain a depth of content, intricate detail is limited. While paying attention to the technical aspects of his craft, such as color temperature, light/values, and composition structure, Mangum says he is guided more by his eyes than by rules.

“It becomes hard, intense work. I wipe away paint or paint over areas again and again until I achieve the effect I want. The focal point of a painting will have some detail but I get progressively looser as I move away from that point,” Mangum said.

Mangum knows when a painting is complete when he has studied it for several days or weeks and no longer has any further corrections or adjustments. He doesn’t like overworked or excessively elaborate paintings and aims to paint just enough specifics to make it convincing to the viewer.

Mangum has always thought of himself as a portrait artist, his earlier Heroic Series from 2017-18 is more typical of the genre. But as he moves toward more narrative, traditionally figurative work in his career, the stories he tells center around people and humanity. The transition he made from portraiture to the Illusions of My Childhood series was sparked by a visit to the National Museum of African American Museum of History and Culture (part of the Smithsonian) in Washington DC in 2018. An exhibit on Emmet Till struck a nerve.

“Till’s lynching in 1955 occurred nine miles from my home. I was a toddler at the time but remember hearing people talking about Emmett throughout my childhood,” he said.

It wasn’t until he saw the exhibition 63 years later in DC that Mangum fully appreciated the depth of the inhumanity that was driven by racism. Mangum was thusly inspired to orient his work around stimulating a dialogue on the subject and says that whatever he paints going forward will continue to address social issues at large.

“The presence of hatred and injustice have certainly informed my entire life, growing up in the Mississippi Delta. The murder of George Floyd underscored the need for work that brings awareness to the level of hatred that still exists today,” he said.

His latest work is evolving from talking about inequality and injustice to calling out passivity, underlining that silence is complicity. He hopes that his work will encourage people to be inspired to practice love, not hate.

“As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. said, ‘In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends.’” Mangum said.

Mangum is an avid reader of both fiction and non-fiction. His current book is Saving Italy by Robert Edsel, an account of Hitler’s military occupation of Italy in 1943 and the seizure of some of the world’s greatest cultural treasures. On the lighter side, Mangum says he occasionally slips away to partake in a game of golf at the Presidio with his wife. He’s also been learning to play the guitar—for the past sixty years.

“I think I have forgotten more songs than most people ever learn,” he said.

Mangum has exhibited at the Wausau Museum of Contemporary Art in Wisconsin, Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, Triton Museum of Art in Santa Clara, and the de Young Museum in San Francisco. He is currently in discussions with a major civil rights museum for a second solo exhibition of Illusions of My Childhood in 2026. Mangum will participate in Winter Open Studios at ICB ART in Sausalito the weekend of December 6–8 and will present many of the paintings from the exhibition for that event.

Artist Stephen Mangum plays introspective observer, and translator of all that he has observed, for our evaluation. For our reflection. And for our willingness to activate a change in the narrative of social inequities.

In much the same way that scholar Isabel Wilkerson has related in her book, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, Mangum urges us not to turn away. Wilkerson writes, “Choose not to look, however, at your own peril. The owner of an old house knows that whatever you are ignoring will never go away. Whatever is lurking will fester whether you choose to look or not.”

Aware that the atrocities from the South of the 1960s still occur today, Mangum asks us to consider that state of affairs, and our own complicity, with the hope of stirring a dialogue that inspires change. He recognizes that it is our responsibility, each of us individually and as a whole, to effectively turn the tide.

“If we want change,” Mangum said, “it is up to us to make it happen.”

For more information, visit his website at stephenmangumartist.com and follow him on Instagram.