Artifacts from the SKZ (through March 1 at Municipal Bonds, SF), a multimedia collection of paintings, sculptures, and drawings by the Los Angeles artist Dan Levenson, in his first San Francisco show, is absurd, ironic, elegiac, and even heartfelt. Those are unusual affects for postmodernist art, which often seems affectless and academic. Levenson has been making his pseudo-artifacts, ostensibly relics from a defunct Swiss art school, the State Art Academy, Zurich (SKZ), for years, so his obsessive fascination with the theme is total. Had the body of work been less commanding, the show would still have been memorable, but even skeptics wary of high-concept but marketable art strategies are won over—especially those who took studio classes. Levenson’s practice reminds me of the heroically Sisyphean corpus of On Kawara, who made a black and white painting of the day’s date, every day, for years, until he died.

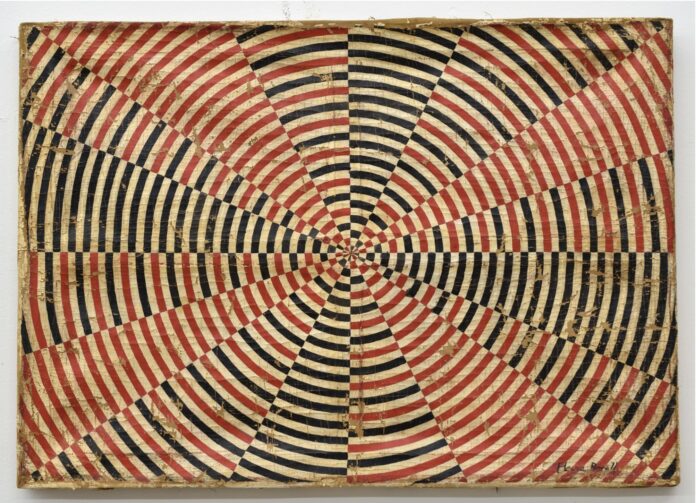

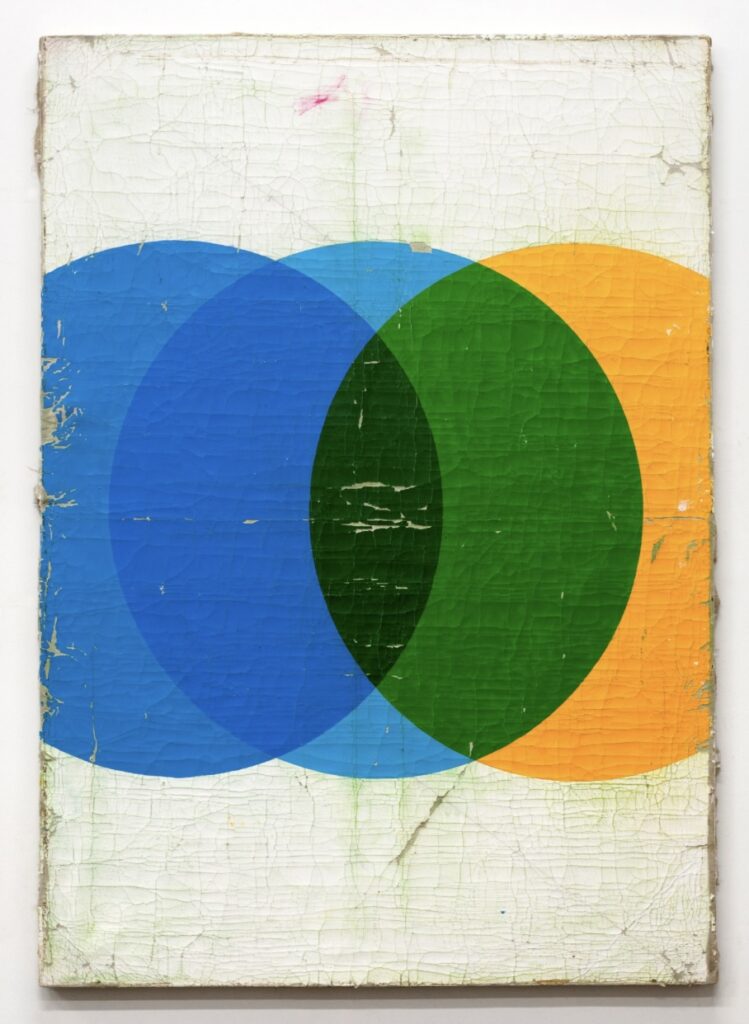

Levenson’s simulated artifacts, unrestored, show the imperfections of wear and negligence that we would expect from student work left unfinished or abandoned at the end of a semester. The oil paintings, which follow the pure geometric abstraction popular in Europe between the wars and in America in the 1960s show dings and chipping, and even warped stretchers and sagging linen—all “defects” that lend them a mute pathos. Readers of a certain age may remember Tom Wolfe’s satirical take in The Painted Word on the ultra-flat paintings of the post-Abstract Expressionist era, when signs of illusionism and narrative were proscribed, as were expressionist traces of the hand-like brushstrokes and painterly texture. Levenson achieves the aged-paint craquelure not by using a contemporary art material designed to produce that effect, but by alternately soaking and baking his canvases so that they reach the desired state of partial dilapidation. (Edvard Munch, incidentally, used to age his paintings in the bracing Norwegian outdoors to test their aesthetic merit.)

The art-studio paraphernalia included in the show—drawing horses, drawing boards, and work tables—are made from plywood, carefully stained the right dark brown and spattered, as are the student aprons, paint-encrusted as Jackson Pollock’s shoes. All the institutional materials are stenciled with identifying numbers and classroom designations, lending the show an archaeological air. The oil paintings on linen and blotting paper are done on metric-sized stretchers and sheets of paper that would have been available in Europe during SKZ’s heyday in the 1990s (though the works seem to belong to the Bauhaus era of the 1930s rather than a mere generation ago). Painting tacks, not anachronistic staples, are used to secure the stretched canvases. There is even a custom-built shipping/storage crate for A3 (42x30cm) paintings, as if eight students had considered exhibiting together but abandoned the project.

In addition, Levenson humanizes his orphaned objets d’art trouvés by attributing them to imaginary students whose first and last names he found in phone books and other sources, combining them at random. Juerg Zwingli, Astid Unholz, Vitus Bruderer, Linus Opp, and Monette Schneiter, take a bow, if you exist somewhere.

In a 2015 interview, Levenson spoke of his core idea of inventing an art school—Swiss, and thus “bland and generic”—arising from jokes with Oberlin College classmates about the plight of new graduates, marketing themselves as shiny and new until replaced by newer models. He appreciated in retrospect his “good fortune of being totally unsuccessful for 18 years” after grad school at the Royal College of Art in London, allowing him time to develop his own voice and to find a way to “allow absolute sincerity or commitment” into his art. Levenson’s functionally anonymous relics can remind of H.G. Wells’ flower from the future in the Time Machine, accidentally transported back to 1895 London—or aesthetically charged objects willed into being by inner necessity, using common art materials.