Part Three of this series on the Berkeley mayoral election, which ran Jan. 2, centered on the East Bay Times/Mercury News’ mendacious threefer: an endorsement of Adena Ishii and attacks on Sophie Hahn and Kate Harrison. Appearing just a week before Election Day, that piece was the most blatant example of media support for Ishii.

Part Four examines a less conspicuous, but if anything, more impactful, aspect of that support: the ongoing coverage of the election. First it reviews commentary in Berkeley’s alternative paper, the Berkeley Daily Planet. Then it turns to the rest of the press and dives into its main subject: the biased treatments of Rigel Robinson’s and Kate Harrison’s resignations from the council.

As Berkeley Daily Planet Editor Becky O’Malley observed in early January, her publication “now is not primarily a news source but a journal of opinion.”

In early October, O’Malley wrote an editorial headlined “Ceasefire Resolution Votes Should Inform Choice of Candidates.” She stated that she’d “always refrained from endorsing candidates on behalf of the ‘The Planet,” and that “[i]instead,” she “sometimes revealed which ones I’m voting for myself.”

This time, she was “reluctant” to support either Jesse Arreguín for State Senate or Sophie Hahn for mayor, due to their “disappointing performance on the matter of the ceasefire resolution.” Their appointees to the city’s Peace and Justice Commission were “some of the most emphatic opponents” of the resolution. Both candidates also sat on the council’s Agenda Committee, “where the ceasefire resolution has been stuck for months.”

In the past, O’Malley had endorsed both of them. Now, she declared, “I no longer feel that I can count on either Arreguín or Hahn to support peace with justice,” adding, “I also no longer trust them to make good decisions on other issues.” Instead, she was voting for Jovanka Beckles for State Senate and Kate Harrison for mayor. Harrison, she wrote, “is “really smart, and has a long history of public policy work, both professional and volunteer.”

As O’Malley implied, Harrison supported a ceasefire resolution on Gaza.

Tacked on to the end of the editorial was a short paragraph about the mayoral contest.

With three candidates, it’s unlikely that anyone will get a majority in the mayor race, so the second choice is crucial. Hahn must be my second choice with Berkeley’s ranked choice voting, since the third candidate, who has approximately no record of civic involvement, is backed by the dreadful YIMBYs, as is Arreguín, But that’s a rant for another day.

O’Malley never wrote that rant. Perhaps she didn’t realize that, unlike Hahn, the unnamed third mayoral candidate supported a ceasefire resolution. Regardless, voting for or against candidates for local office in Berkeley on the basis of their positions on the Israeli-Palestinian war is absurd. In this case, it may have led O’Malley’s readers to support a candidate she effectively called “dreadful.”

In mid-October, former Rent Board Chair Paola LaVerde and community activist Kelly Hammargren attacked Hahn in the Planet for having allegedly failed to disclose her family’s income and stock holdings as required by law. LaVerde reported that she’d filed a six-page complaint with the California Fair Political Practices Commission. Observing that Hahn’s husband is a former biotech executive, and that biotech executives had contributed to her mayoral campaign, Hammargren and LaVerde tied Hahn’s alleged violation of the law to her support for two items on the council’s agenda that favored the expansion of biotech startups in the city.

At the same time, the Planet ran a piece by Harrison denouncing one of the items, a proposed expansion of the city’s exemption of businesses receiving research and development grants (think tech startups) from its business tax. Piling on, O’Malley wrote an editorial headlined “Berkeley Mayor Backs Giant Tax Giveaway to Tech Interests.”

On November 12, five days after the election, the item appeared on the council’s agenda. During the meeting, Hahn read a letter from the FPPC that dismissed LaVerde’s complaint, stating that the interests LaVerde cited were not in Berkeley, and that as such, “the Enforcement Division found that “proper disclosure has been made.”

On November 1, the Planet posted an op-ed by Harvey Smith entitled “Hahn’s Hypocrisy.” Smith was one of the litigants against UC’s People’s Park housing project. He assailed Hahn for having supported the project and now, as a mayoral candidate, advocating “urban forests” in Berkeley. Describing People’s Park as “an urban forest ecosystem that was developed by the community over more than a half-century,” one that “has many redwoods and mature oak trees and other California native trees,” Smith contended: “Obviously it is nonsensical to destroy the established urban forest that is People’s Park and then call for recreating it elsewhere.”

Was he unaware that in mid-September, Adena Ishii had been jointly endorsed by Buffy Wicks, who authored the 2023 bill, AB 1307, that killed the lawsuit against the People’s Park housing project; and by State Senator Nancy Skinner, who authored the 2022 bill, SB 118, that removed public college enrollment as a separate consideration under the California Environmental Quality Act?

Given the importance of that endorsement—Ishii called it “a game changer for our campaign”—it’s unlikely that she opposed the project or, for that matter, opposed the university’s larger expansionist agenda.

To wit, here’s her reply to the Green Party’s question about UC’s takeover of the park.

People’s Park, with the erecting of a shipping container wall complete with barbed wire and 24/7 guards, continues to be a blight on the City. How will you address this blight? Would you favor Council asking the Regents to donate People Park to the Ohlone as an act of reparations and to provide D7 open space?

Ishii, who co-chaired the BUSD Committee on reparations, dodged the question:

– I was and continue to be horrified by the way People’s Park has been essentially turned into a war zone. It is highly inappropriate and disrespectful to surrounding residents. I know children who are disturbed and frightened by this shipping container fortress.

In other words, what she objected to was the manner in which UC acted, not the seizure of the park for housing.

After the Wicks-Skinner endorsement, Ishii’s political capital surged. From then on, attacking Hahn could only benefit Ishii’s candidacy.

The Planet also published two exceptions that departed from the anti-Hahn, pro-Harrison line.

In mid-October, a piece of mine addressed Harrison’s newfound opposition to City Hall’s encouragement of tech start-ups in West Berkeley—which is to say, its facilitation of UC’s further encroachment on the city’s economy and decimation of its light industrial and artisanal sector. As a councilmember, for years Harrison had either sponsored or voted for legislation that encouraged tech businesses, including biotech, in the city. In my view, the problem wasn’t that she’d changed her mind; it was that she didn’t say she’d changed her mind, or why. Considering that few members of the public knew that history, the omissions smacked of political opportunism. In reply to my query, Harrison denied having switched her position.

Far more important was longtime community activist Rob Wrenn’s take on the 2024 election at large. Posted in early October, the piece included a section entitled “Berkeley Mayor—Does Experience Matter?”

Wrenn began by noting that both Hahn and Harrison had “extensive experience on the City Council” and had demonstrated familiarity with Berkeley’s adopted” plans and polices, which they had recently “helped shape.” Wrenn favored Harrison “because of her leadership and record on affordable housing and addressing climate change.”

By contrast, Ishii

has never held elected office, or served on any of Berkeley’s major commissions or boards (e.g. Planning, Zoning, Housing, Transportation and Public Works, Rent Board).

Her only real experience in local government is as a member of Soda Tax advisory panel that recommends how Soda Tax revenues should be spent. She has also been active in the local League of Women Voters. It’s admirable that she has volunteered her time, but does that qualify her to be mayor?

Not in Wrenn’s judgment. He explained why:

This writer heard Ishii speak at candidate’s forum at St. John’s Presbyterian Church and was not impressed. She started out by describing herself as “a leader in local politics” for the last ten years. Really? She has also exaggerated her role in passing Measure O, the affordable housing bond measure in 2018. Both Harrison and Hahn played a bigger role.

She wants a “reset” at City Hall. But what kind of reset would she bring?

Asked a question about whether a bond or parcel tax measure was best for repairing Berkeley’s streets, she didn’t, unlike her opponents, show any understanding of the difference.

Asked about giving the public a vote on Missing Middle [housing proposal] changes, she was against, while both her opponents were for it. She was afraid voters might reject the changes, and they probably would if they were voting on the extreme version the Planning Commission proposed.

The complacent—or is it complicit?—press

To my knowledge, Wrenn’s piece was the only critical analysis of Ishii’s campaign published before Election Day. Instead, the public was offered she said/she said/she said-style reportage.

The best such reporting about the mayoral election was produced by the Daily Cal. But I can think of only one instance in which the paper’s news staff even hinted at a questionable aspect of Ishii’s candidacy. The query, which I cited in Part One of this series, was about why she wasn’t running for the council seat in District 3, where she lived. Otherwise, the reporters essentially transcribed statements made by Ishii and her rivals.

I’ve drawn extensively on the Daily Cal’s coverage. I’ve also referenced many articles that appeared in Berkeleyside that reported on the election and City Hall politics. I’m grateful for their work, without which I couldn’t have begun to understand what happened.

But to fully grasp Ishii’s victory, it’s necessary to probe what people—including media people—say and do—and even more importantly, what they don’t say and do—and then situate what you find in larger contexts—above all, the context of political power. Too often reporters not only took things at face value; they also framed their articles and cited sources and evidence that favored Ishii and the ascendant Yimby regime.

The January 2024 resignations of Councilmembers Rigel Robinson and Kate Harrison were cited by Ishii’s campaign in support of her central claim: Berkeley’s “city government has become broken and toxic, and if we’re too busy fighting each other, we’re not focused on our problems.” To make the two withdrawals fit that allegation, Ishii conflated Robinson’s and Harrison’s motives, presenting both resignations as responses to unwarranted contentiousness and ignoring the ideological aspects of disagreements both on the council and within the public. Her obfuscations were never challenged by the press. Instead, the coverage of the resignations tacitly corroborated her argument.

Berkeleyside’s disparate treatments of the Robinson and Harrison resignations

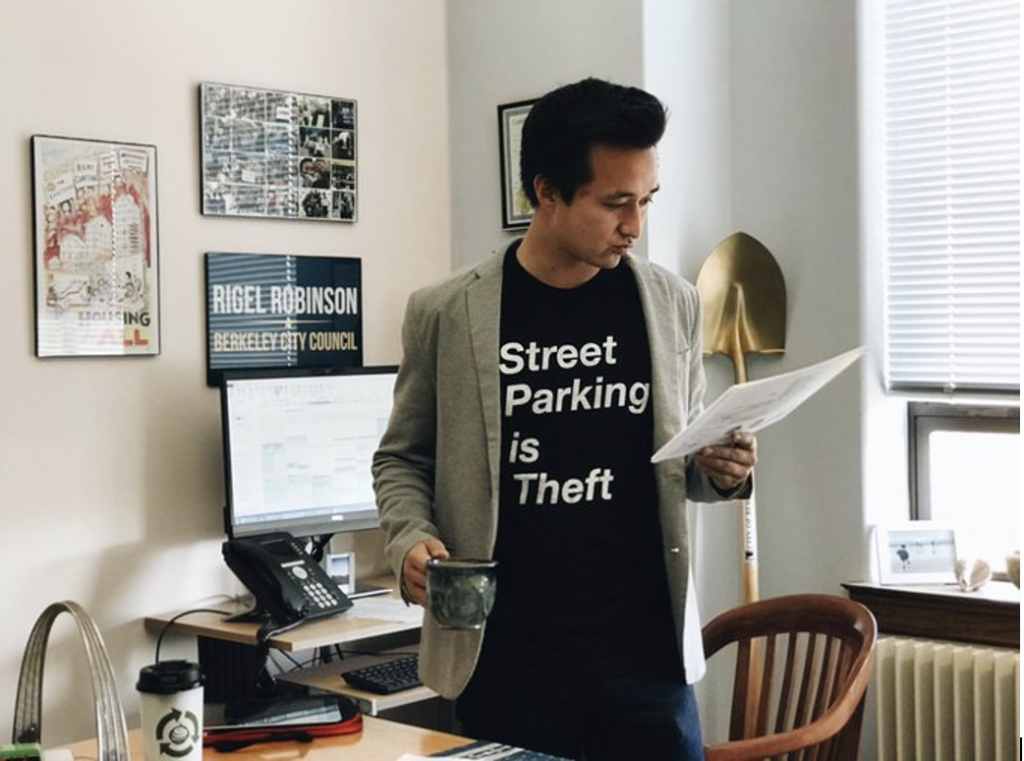

On January 9 Berkeleyside associate editor Nico Savidge reported that “roughly five years after he became the youngest person to be elected to the Berkeley City Council in 2018 at the age of 22,” Rigel Robinson had announced his “‘retirement.’” Robinson attributed his decision to “harassment, stalking and threats” that had left him “exhausted” and “burnt-out.” At the same time, he ended his mayoral candidacy, which had been endorsed by “three of his City Council colleagues, along with influential advocacy groups such as the Housing Action Coalition and East Bay Yimby, and a long list of politicians from around the region and state, including Attorney General Rob Bonta.” Savidge called the move “a stunning turn for a young elected official who seemed to be eyeing an ascent through the ranks of East Bay politics.”

Robinson texted Savidge that “he ha[d] been followed and told to kill himself, and that concerning messages were taped to the door of his home and mailed to him.” He said that much of this behavior was a response to his support for UC Berkeley’s proposed housing development at People’s Park. He’d “discussed his concerns with Berkeley police and considered seeking restraining orders ‘against multiple individuals,’ but did not go through with the process,” nor did he name any of his alleged harassers.

Savidge noted that “[d]uring his time on the council,” Robinson had been

a strident supporter of efforts to build more housing in Berkeley, backing the city’s work to eliminate single-family zoning and another package of zoning changes adopted last fall that raised height and density limits in the Southside neighborhood. He also advocated for projects to provide more space for public transit, bicyclists and pedestrians on Berkeley streets, particularly a proposal to ban cars from the north end of Telegraph Avenue.

The article linked to a Berkeleyside opinion piece in which Robinson touted additional achievements, including having “invested in our beloved but crumbling waterfront, putting us on track to reopen the Berkeley Pier with a ferry terminal to connect the region;….reforming our zoning code to foster new research & development jobs”; and having “fought back and won when litigious neighbors sought to slash enrollment at UC Berkeley.” The last of these referenced an op-ed in the Los Angeles Times that he’d co-authored with Arreguín and former Councilmember Lori Droste.

Every one of the achievements Robinson marked in his Berkeleyside oped had been controversial. But the only hint of criticism in Savidge’s article was the allusion to People’s Park and the description of Robinson’s political style as “strident.” The piece concluded by citing the “support and well wishes” he’d received from Arreguín and Councilmember Terry Taplin.

It’s as if the egregiousness of Robison’s allegations insulated him from disparagement of his record. At the same time, Savidge’s account of Robinson’s withdrawal lent credence to Ishii’s claim that divisiveness had made Berkeley’s public processes “toxic.” The piece included a Taplin post on X that generalized the problem: “The harassment & abuse public servants face is real. This toxicity should never be normalized.”

Three weeks later, Savidge reported that Kate Harrison had “abruptly resigned in the middle of a Berkeley City Council meeting” but intended to continue her mayoral campaign. The article included a Berkeleyside tweet that displayed Harrison’s resignation statement.

Reviewing the contents of the statement, Savidge first noted that, “[u]nlike Robinson, Harrison wrote that she did not decide to resign because of harassment.” True. But his summary of her complaints was misleading. “Instead,” he continued,

her statement touched on more than a dozen topics, ranging from local bond measures to the end of the Berkeley Kite Festival. Harrison raised concerns about housing policies that don’t take into account shadows new buildings may cast on neighbors’ solar panels, UC Berkeley’s increasing enrollment and practice of “master leasing” privately built apartment buildings, the future of the city’s waterfront and debates over law enforcement practices.

The impression here is that Harrison published a laundry list of grievances.

In fact, she repeatedly stated that her charges exemplified a general problem: “Berkeley is relying on the market as the ultimate arbiter.” “[A] focus on private profits impacts how we do everything.” The actions taken by the council are all designed to reassure “nervous” “development interests.”

Savidge also blunted Harrison’s jab at Berkeley’s public process. Her resignation statement, he wrote, “touched on a wide range of local issues where Harrison contends the city is not adequately addressing residents’ concerns.” Her actual contention was more pointed: “Issues are presented as a morality play with those who disagree”—not just residents—”cast in the role of villains.”

As for responses to Harrison’s withdrawal, Savidge again cited only city officials. Whereas the tributes to Robinson that he reported had all been positive, the remarks about Harrison were mixed. Mayor Arreguín allowed that she had been “an integral part of the city’s leadership team, helping advance important policies combating climate change and building affordable housing.”

By contrast, Hahn, at the time Harrison’s major rival in the mayoral election, criticized Harrison’s decision to “abandon her constituents and all the people we serve….for no particular reason other than disagreement with some colleagues on some issues” as “shocking.”

Savidge also cited Taplin’s rebuke of Harrison for swearing at him at the council meeting after her resignation announcement. The reporter documented that incident with a thirty-second video posted on X by Daily Cal reporter Anna Armstrong. The post also displayed a tweet from Taplin that expressed “zero tolerance for discourtesy, let alone racial micro-aggressions [especially] in this climate of toxic political discourse.” Savidge followed that dispatch with a tweeted riposte from Harrison who accused Taplin of having repeatedly interrupted her, “even when I told him it was not OK for a man keep interrupting me. It is sexist, unacceptable, and I will not stand for it.”

Given Harrison’s criticism of her colleagues, their ire was unsurprising. What’s notable is their failure to grapple with her charges. Hahn discounted them as “disagreement with some colleagues on some issues.” But Harrison’s claim that the city was pursuing a destructive, market-friendly agenda was sweeping and profound. Arreguín and Taplin simply ignored that claim. Perhaps, consistent with his own attenuation of Harrison’s critique, Savidge didn’t ask them to respond to her attack.

Whatever the reason, the upshot was another account that corroborated Ishii’s assertion that squabbling, particularly on the council, had ‘broken” Berkeley’s public processes.

The Daily Cal: more of the same plus an anomaly

The independent, student-run newspaper ran two short articles about each of the resignations. Referencing the Berkeleyside piece, the first article cited Robinson’s description of “death threats, stalking, and a ‘perpetual state of stress and exhaustion’” that, he’d said, had “permeated his tenure on the council.” The authors, Riley Cooke and Sandhya Ganesan, observed that he’d been endorsed by three councilmembers, Taplin, Mark Humbert, and Rashi Kaserwani. They also mentioned his support for upzoning the Southside neighborhood and his introduction, “quickly retracted,” of a resolution for a ceasefire in Gaza.

Cooke and Ganesan made a point that clashed with the other coverage of Robinson’s resignation. The departed councilmember presented himself as the avatar of politically righteous youth in Berkeley and beyond. Other reporters either unquestionably cited his self-description or roundly seconded it.

By contrast, Cooke and Gamesan first noted that Robinson represented “the student-majority Southside district” that includes People’s Park. They then flagged two of his stands that had offended his student constituents. The first was his support for housing at the park.

The district has recently been the center of attention after UC Berkeley walled off People’s Park with shipping containers last week. Robinson was a staunch advocate of housing at the site, a stance that often put him at odds with many students and homeless activists who resided in his district.

The other troubling position was Robinson’s support for relocating Berkeley’s Telegraph Avenue chess club. “Between People’s Park and the Telegraph chess club, Robinson,” wrote Cooke and Ganesan, “faced a barrage of protest and criticism at City Council meetings last fall from students and other residents of his district.”

They concluded by stating that he “could not be immediately reached for comment.”

On January 18, the Daily Cal published a second piece about Robinson’s resignation. Other than a sentence noting that his “terms produced contention regarding land use in the 7th District,” this article adulated Robinson. Under the headline “‘Berkeley was lucky to have him’: Mayor, council members respond to Rigel Robinson’s resignation,” the authors, Anna Armstrong and Chesney Evert, repeated the ex-councilmember’s allegations of harassment and then cited praise from Arreguín, Taplin, Humbert, Kesarwani, Hahn, and Ishii. Like Savidge, they cited none of his critics, including any students.

The absence of student commentary is particularly striking, given that the Daily Cal is a student-run paper and, more to the point, their colleagues’ prior references to the discontent of Robinson’s student constituents in his former student-majority council district.

At the same time, Armstrong and Evert savaged Robinson’s alleged harassers. They reported that in an interview, Taplin had “commend[ed] Robinson for prioritizing personal safety,” but

also examined the ways in which the departure represents a larger threat to public discourse in Berkeley. We’re the intellectual leaders of the world and the champions of forward-thinking, but we can’t handle disagreeing about policy”…Why is it acceptable to harass someone just because you disagree with something? Violence for political outcomes is never acceptable.”

The reporters followed Taplin’s post on X with a statement from Humbert: “Cautioning against ‘‘‘cutthroat’” democracy…., Humbert noted that civic discourse should be “‘vociferous’ but never ‘violent.’”

The designation of Robinson’s alleged harassers as violent would figure even more prominently in other publication’s coverage of the resignations.

Like Robinson’s departure, Harrison’s resignation was reported twice by the Daily Cal. Published on February 1, both articles scanted her stated reasons for resigning. The first piece devoted two short paragraphs to her resignation statement. After citing her disavowal of harassment as a factor in her withdrawal, reporters Anna Armstrong, Chesney Evert, and Swasti Singhai wrote:

She went on to assert that Berkeley’s “processes are broken,’” adding that she “cannot in good conscience” serve on the council.” Harrison’s resignation statement outlined the issues of housing inequality, climate change, and the monetization of public space, and it alleged that the city’s current processes will not induce effective solutions.

They followed that passage with a review of her colleagues’ responses, which ranged from “shock” (Hahn and Humbert) to denunciation (Taplin) to surprise and disappointment (Bartlett).

Taplin, they reported, posted a statement on X “describing her actions as a ‘dereliction’ of duty. Abandoning one’s District & constituents while claiming to run for mayor of this city is a travesty & does not represent the values of this community.’” Armstrong, Evert, and Singhai also recounted the tense exchange between Harrison and Taplin at the council after her announcement, in which he told her not to swear at him.

They did not note her riposte: she said he had repeatedly interrupted her. Nor did they observe that Harrison was not, as Taplin stated, just claiming to run for mayor; she was actually doing so.

The other Daily Cal article about Harrison’s resignation presented an overview of her “seven-year legacy.” Authored by Armstrong alone, it noted that she’d “authored legislation aimed at expanding affordable housing in the city,” “initiated efforts related to clean energy as a member of the East Bay Community Energy Board,” written an open letter to UC administration asking the campus police and other city agencies to abide by ‘less lethal’ weapons rules against nonviolent protesters during the barricading of People’s Park in early January.” Armstrong cited only one response to Harrison’s resignation, Arreguín’s perfunctory acknowledgment of her work combating climate change and building affordable housing.

What’s notable about the Daily Cal coverage of the resignations is that, as in Berkeleyside’s stories, Robinson’s complaints are taken more seriously than Harrison’s.

With Robinson, the focus is on his accusations of harassment and his need to protect his mental health.

With Harrison, the reporters’ focus is on her withdrawal, not her stated reasons for withdrawing. To their credit, Armstrong, Evert, and Singhai included the “monetization of public space” among her grievances. But there’s no indication that the Daily Cal staffers asked Harrison’s former colleagues to comment on her assessment of the city’s policies and public processes. All they report is reactions to her decision to jump ship, which, predictably, are all negative. Robinson’s withdrawal comes across as justified; Harrison’s appears as irrational and irresponsible.

What was irrational about Harrison’s resignation was her decision to continue her mayoral candidacy. Reporters could have separated that decision from her critique and delved into the latter. They didn’t.

Coupled with their solicitous take on Robinson’s resignation, their framing tacitly supported Ishii’s line: the city’s policy direction is sound; the problem is “noise,” i.e., disruptive challenges to that direction.

The Chronicle: Robinson a martyr to Nimby violence, Harrison a negligent autocrat

The Chronicle’s treatments of the two resignations were even more disparate than Berkeleyside’s and the Daily Cal’s, affording Ishii correspondingly greater rhetorical benefits.

Robinson’s withdrawal merited a 1450-word screed published on January 12 and authored by the Chronicle’s senior political writer, Joe Garofoli. Robinson’s departure, Garofoli wrote,

shows how toxic and dangerous our politics has become—even in cities that tout their inclusivity. The impact isn’t hard to predict. If those on the fringes of our system can destroy a young person bursting with enthusiasm about public service, why would other young people sign up for that? Particularly young people of color, like Robinson, who is Korean American, given the dearth of diversity in politics.

Arreguín agreed, telling Garofoli that

[t]he toxicity of political discourse is really concerning if young and dedicated people like Rigel decide to quit because they can’t deal with death threats, harassment. We are losing a brilliant and dedicated leader,..someone who is the voice of students and the next generation.

Stating that he’d “‘also been the target of harassment and death threats,’” Arreguín said that he wasn’t surprised that Robinson had been hounded, though unlike his former colleague, the mayor got a restraining order against his antagonist.

The harassment didn’t surprise Garofoli either. “Political violence,” he wrote, “isn’t new; it is just more culturally accepted—and it starts at the top and trickles down.” He noted among other things Trump’s threat to judges, bomb threats to public officials, the attack on Paul Pelosi, and the intimidation of local poll workers.

The implication was that whatever Robinson experienced—once again, he’d “declined to go into specifics about the harassment”—was just another form of “normalized” “toxicity.” In Robinson’s case, the ugliness was a reaction to “his YIMBY attitude toward housing,” a position that, Garofoli wrote,

was unusual in traditionally NIMBY Berkeley. Yet that opposition began to thaw, thanks in part to Robinson and others on the council. The city ended exclusionary zoning during his tenure, and its homeless population decreased.

Unlike Savidge, Garofoli cited one of Robinson’s opponents, Harvey Smith. As noted above, Smith was among the litigants who challenged UC’s plan to build housing on People’s Park. The park is in the council district that Robinson represented. Smith told Garofoli that he “[didn’t] know of any housing opponent who has harassed Robinson and called any such attacks ‘disgusting,’” adding “‘I think there are other ways to have a discussion and to talk things through.’”

Smith also criticized Robinson’s politics and questioned his fitness for the office he was leaving.

I don’t consider him a progressive candidate for district, so I don’t bemoan him leaving. You’re on the Berkeley City Council. So, it’s like the old saying, “If you can’t take the heat, get out of the kitchen,’ and I guess maybe that’s what he’s done…”

Wedged into a fulsome eulogy for Robinson, the citation of Smith’s remarks comes across as a cynical gesture toward reportorial evenhandedness. Garofoli had already categorically stated that Robinson “was a progressive.” He could have asked Smith what he meant by the label and why he thought it didn’t apply to Robinson. Even better, he could have initiated a discussion about the different ways that he and Smith defined the tag.

Instead, he proceeded to cite Robinson’s dismissive pushback against his critics: “‘If people feel like they won by my leaving,….I sincerely hope they find the happiness that’s missing in their lives.’” His opponents, then, were malcontents who displaced their personal grievances onto city politics, thereby exercising, as Garofoli put it, “the heckler’s veto that’s turning local politics into pro wrestling.” But to no avail: they’re losing, Robinson observed. He “point[ed] to the changing attitude toward building housing in Berkeley as proof that his term on the council reshaped the city,” ignoring the fact that the build-baby-build agenda he championed had been advanced by other members of the council—most notably Arreguín and Droste—for years before his election in 2022.

Garofoli noted that while Robinson is leaving elective office, he “isn’t leaving policymaking.” During his council tenure, he “received his graduate degree in public policy from UC Berkeley and will look for a policymaking job that is a little more behind the scenes.” Another win, this one personal, with the potential for future professional success.

In a final tribute to Robinson/swipe at his critics, Garofoli underscored Robinson’s concern that his resignation would discourage young people from activism. “He urged young people not to give up and said the changes in Berkeley would not have happened “‘if not for the level of involvement of young people in our city and in our politics.’” Coming at the end of a lengthy homage to both the speaker and the changes, that quotation identified youth with amelioration and age with regression. The student opposition to Robinson noted in the Daily Cal was nowhere in sight.

The Chronicle initially covered Harrison’s departure from the council on January 12 in a 300-word article by then-intern Jordan Parker that read like a highly condensed version of Savidge’s story, which had been published three days earlier.

Two weeks later, the paper published a 700-word piece by Sarah Ravani headlined “Resignation of Berkeley councilor is criticized by some city leaders.” Noting that Harrison’s withdrawal had come “less than a month after Rigel Robinson, the youngest person ever to be elected to the Berkeley City Council had stepped down and ended his own mayoral campaign,” Ravani echoed Garofoli’s emphasis on the poisonous nature of current politics. “Both resignations,” she wrote, “come at a time when the political climate in Berkeley and nationwide has turned increasingly confrontational and nasty.” Robinson said “he was burned out by harassment and the toxicity around him.”

The image of enveloping malignancy was reinforced by a comment from Taplin, the one that had been cited in the Daily Cal—“‘People treat our local agencies like political games….[,]embrac[ing] this culture of toxicity and harassment”—and by Ravani’s observation that “[o]ver the past few months, protesters have also disrupted council meetings, demanding a city resolution supporting a ceasefire in Gaza.” In this framing, nastiness was not directed at a particular politician but at public officials in general.

Ravani proceeded to sandwich Harrison’s claims between the comments from her former colleagues deploring endemic hostility and their aspersions on her peremptory style. The specific problems Harrison flagged in her resignation statement were disposed of in a single sentence: “In her public statement, she had raised concerns about numerous city policies, including design standards for buildings, affordable-housing funding, and the impact of UC Berkeley’s growing enrollment on housing and city services.”

Another laundry list of “concerns, although at least Ravani flagged the elephant in the room, university expansion. Missing was Harrison’s over-arching category: Berkeley’s “rel[iance] on the market as the ultimate arbiter” of city policy.

In Ravani’s telling, it was Harrison’s critique of Berkeley’s public process, not public policies, that mattered most. “‘City Hall is broken,’” Harrison “told the Chronicle….‘I don’t believe the mayor and the councilpeople know how bad it is. They’re out of touch’.” Council “meetings are not productive or useful….A very small part of the job is actually going to council meetings. Much more of the job should be focused on talking to people’.”

This is a watered-down version of the charge in Harrison’s resignation statement, in which it’s not just “people,” but dissidents whom her colleagues spurn.

Next, Ravani observed: “While Robinson received an outpouring of support from council colleagues and other political leaders in the Bay Area following his resignation, some current and former Berkeley councilmembers criticized Harrison for hers.” Rather than explaining the divergent responses to the resignations, Ravani cited two critics of Harrison’s critics.

First, Taplin:

“This is not normal….This is not how we govern cities. This is not how we pursue progressive platforms, and this is not how we create change….Democracy is compromise.”

Then came former councilmember Lori Droste, who in 2022 (not, as Ravani wrote, 2023), had chosen not to run for re-election. Droste called Harrison’s resignation “‘rash,’” adding: “‘As electeds, we have to understand that people will disagree with us on issues.’”

Two of these judgments were irrefutable: Harrison’s sudden resignation was certainly abnormal. Elected officials resign, but rarely in the middle of an official meeting and even more rarely by pointing to their colleagues’ behavior as the thing that drove them to step down. And despite Harrison’s insistence that her action was premeditated, it’s hard to see it as anything about rash.

But was her behavior also, as Taplin alleged, unprogressive, reactionary, and undemocratic? The answer to that question depends on the meanings of those terms. Let’s assume that Taplin thought he and the rest of the council were pursuing a progressive agenda on behalf of democratic change. But did that understanding jibe with Harrison’s twofold critique of city policy as market-driven and the city’s public processes as peremptory? Probably not. In any case, Ravani apparently didn’t ask.

Likewise, Droste’s pronouncement that elected officials need to “‘understand that people will disagree with us on issues’” begged the question: which issues? Neither she nor Taplin specified their disagreements with any of the charges in Harrison’s resignation statement. Again, Ravani gave no indication that she’d asked them to do so. Not did she give Harrison an opportunity to respond to their accusations.

Both Taplin and Droste turned Harrison’s accusation that the council didn’t brook opposition against Harrison herself. Rather than compromise, she quit. But Harrison had complained about the council’s censorious treatment of dissenters at large, not just herself. Nobody from the public was cited in Ravani’s piece. The upshot was another article reprising the council-centric dynamic that Harrison decried.

The contrast with the coverage of Robinson’s resignation was striking. He, too, had abandoned his constituents, but the press depicted his withdrawal as valid, because it was driven by the need to protect his personal well-being from alleged instances of harassment. Unlike Robinson, Harrison backed up her criticisms with specifics, but her resignation was deemed questionable, its probity undermined by her vulnerability to the very thing she criticized: the unwillingness to compromise. The substance of her manifesto was lost in transmission.

The East Bay Times and Business Insider: Robinson canonized, Harrison ignored

But at least the Chronicle reported Harrison’s withdrawal. Two other publications that covered Robinson’s resignation, the East Bay Times and Business Insider, didn’t.

The East Bay Times story, written by Katie Lauer, encapsulated the laudatory Berkeleyside account, which it referenced. Stating that the departing councilmember wasn’t available for an interview, Lauer cited Arreguín’s and Taplin’s praise for their former colleague and added a kudo from Droste: “‘From staffers to elected colleagues, you’ll find a chorus of people who loved him.’” Translation: he was popular inside City Hall. No detractor was cited.

Three weeks after Robinson’s departure, Business Insider devoted 1,100 words to Robinson’s departure. Berkeley politics isn’t one of its regular beats. But it regularly cheers on Yimbyism, which explains its interest in Robinson’s withdrawal from official life.

Like the other media accounts, the Business Insider piece focused on Robinson’s age, his push for more housing, and the pushback against that push, especially with respect to People’s Park. Once again, no critics were cited. All readers got was Robinson’s disparaging take on protesters.

That said, Ayelet Sheffey and Eliza Relman presented a more complex, if still biased, picture of the controversy over housing in Berkeley than other journalists who covered Robinson’s resignation. UC’s bid to build housing at People’s Park, they wrote, “has divided the progressive community, pitting pro-housing YIMBYs — which stands for “Yes In My Backyard” — against so-called ‘left NIMBYs,’ who oppose new development on the grounds that it hurts lower-income and marginalized people.” Raising the class issue, Sheffey and Relman momentarily gave Robinson’s opponents more credit than any of the other journalists covering his resignation.

The operative term is “momentarily.” The next sentence undercuts the opposition’s credibility: “In response, advocates for new housing development point to numerous studies have found that even the addition of market-rate housing helps bring down costs in a community and lowers the risk of displacement.” This is true. What’s also true but not noted is that scholars increasingly contest this finding.

One of the dissenting researchers is Karen Chapple, the former professor of planning at UC Berkeley who now leads the University of Toronto’s School of Cities. Chapple co-authored a 2024 paper entitled “Can New Housing Supply Mitigate Displacement and Exclusion? Evidence from Los Angeles and San Francisco.” The answer to that question: sometimes.

Chapple and Taesoo Song wrote:

Developers are most keen to build in neighborhoods with the greatest return, which are also [a] city’s hottest markets. Our results indicated that this will help mitigate displacement and exclusion in such areas in Los Angeles but likely not San Francisco. This suggests that neighborhoods generally benefit from new construction; the exception is superstar cities with global demand for their real estate.

Another exception, unremarked by Chapple and Song, is places that have a built-in demand for their real estate. Berkeley qualifies. It’s not a superstar city, but it’s a red-hot housing market. That’s partly because of its proximity to San Francisco and Silicon Valley, and its many attractive homes and neighborhoods. Those two factors alone would guarantee high housing prices.

But there’s another thing that drives up Berkeley housing costs: UC’s relentless growth.

Berkeley housing pressured by UC growth

As Frances Dinkelspiel reported in Berkeleyside in July 2021, “UC Berkeley’s enrollment has increased by more than thirty percent” in recent years. The campus’s 2021 Long-Range Development Plan” said the student population

would grow to 33,450 students by 2020. But driven by a mandate by the UC Board of Regents, there were 42,347 students in the 2019-20 academic year. By 2036, there will be 67,200 people on campus, including students, faculty and staff.

Meanwhile,

UC Berkeley only houses 22% of its undergraduates and 9% of its graduate students — the lowest percentage in the UC system. (The average across the system is 38.1% for undergraduates and 19.6% for graduate students.) UC Berkeley has plans to build 11,730 beds in the next 16 years but that would still leave 70% of Cal students to find a place to sleep outside the Cal system.

In a May 2022 overview of UCB’s historic failure to build more housing, Dinkelspiel observed: Since about 70% of UC Berkeley students don’t live in university-supplied housing, there is a huge demand for housing supplied by others,” which is to say, private developers.

According to Berkeley’s 2020 housing pipeline report, about 1,351 units have been constructed since 2015. There are 3,880 other units either proposed and pending review, approved without a building permit, or have a building permit but are not yet occupied. Not all of those are aimed at students, but many are.

The private dorm construction spree has continued. Meanwhile, “Cal leases out entire apartment buildings for student housing…and then offers the rooms directly to its students,” putting even more pressure on the city’s housing stock.

Arreguín council pushes UCB expansion: the enrollment cap

The most unfortunate aspect of the fight over UC’s plan for housing at People’s Park was that the focus on the park’s storied history and the plight of the homeless obscured the underlying issue: UC expansionism. The crushing impact of the school’s growth on the city of Berkeley and the council’s pandering to UC should be at the center of the town’s politics and the press’s treatment of that politics—including the 2024 mayoral election. Instead, in both contexts that impact is downplayed, mystified, or simply ignored.

Basic facts: University property is exempt from the city’s zoning. It’s also exempt from property taxes.

In 2018, Save Berkeley Neighborhoods sued the university, alleging that it had violated the California Environmental Quality Act by failing to study the environmental impacts of its enrollment increases. As Dinkelspiel reported in 2021, “[a]s UC Berkeley increased its enrollment without building enough new beds to accommodate the growth, investors rushed in to convert single-family homes into places where a dozen or more students could live.” City of Berkeley records showed that the Southside neighborhood had “eight houses crammed with students….Most of the renters pay $1,000 or more for a place to sleep. Not a separate bedroom. A place to sleep.” Unsurprisingly, “the proliferation of minidorms in Berkeley’s residential neighborhoods [had become] a flashpoint pitting long-term neighbors against students, the city, and the university.” The problem, from the neighbors’ standpoint: “young people living together with minimal adult supervision can mean noise, late-night disturbances, parties, trash and increased calls to the police.”

The Alameda Superior Court sided with Save Berkeley Neighborhoods. UC appealed to the First District Court of Appeals and lost again. The campus froze its enrollment but said it would appeal to the California Supreme Court. In February 2018, the Berkeley council unanimously voted to submit an amicus brief opposing an enrollment cap. Three weeks later Skinner introduced SB 118, a gut-and-amend bill decreeing that “changes in enrollment” are exempt from CEQA. Placed on the legislative fast-track, SB 118 was approved a few days later and signed into law by Governor Newsom. End of litigation.

UC’s 2021 Long-Range Development Plan

Meanwhile, in April 2021, the city itself had sued UC over the campus’s latest Long-Range Development Plan. The city’s initial response to the plan was harsh. But when the council met in closed session in July, it settled the suit in an agreement that capitulated to UC (see Attachment A), with Harrison casting the sole No vote. The new LRDP anticipated a campus population of 67,200 comprising 48,200 students and 19,000 faculty and staff.

Berkeleyside highlighted the financial aspects of the settlement. The university had been paying the city $1.8 million a year for its use of Berkeley’s fire, police, and sewerage. Under the terms of the new settlement agreement, it would pay about $4.1 million. Dinkelspiel cited the self-congratulatory joint statement issued by UC and the city: “The agreement represents one of the largest financial settlements a UC campus has provided to a post city and paves the way for expanded educational opportunities, while balancing community concerns and prospective impacts on city services.” Her story was accompanied by the official photo of Arreguín and Chancellor Carol Christ shaking hands.

A less sanguine view appeared in in the Daily Planet, where David Wilson and Dean Metzger argued that “[i]n real dollar terms U.C. currently pays less today than it agreed to pay in 2005” under the agreement that settled the Bates council’s lawsuit the university’s prior Long-Range Development Plan. “When the 2005 payment is adjusted for inflation and the added costs of a near doubling of the student body,” they wrote, “it is obvious that the new deal is as bad as the old. Indeed it is worse.”

The Berkeleyside piece also glossed over the city’s submission to the campus’s broader authority over land use. Dinkelspiel reported that in exchange for UC’s money, the city would withdraw from its two lawsuits over specific projects, the Upper Hearst Project and volleyball courts at the Clark Kerr campus; would not oppose the Anchor House or the People’s Park housing project; or sue the university over the 2021 LRDP.

She did not report that if the city did sue over these projects, the entire agreement would be terminated, meaning no more payments to the city (Section 6.5), even though the campus use of city services would presumably continue. She didn’t ask: Why should payments for city services be conditioned on Berkeley’s submission to UC authority in the first place?

Housing at People’s Park

During the fight over housing at People’s Park, the council again displayed its fealty to UC.

UC owns the People’s Park site. Under state law, the city couldn’t legally stop the school from building housing or anything else there.

But before the settlement of the 2021 LRDP lawsuit, the council, remembering that it’s elected to advance the interests of the city, not the campus, could have objected to the project. Using his office as a bully pulpit, Arreguín could have publicized the inordinate demands that UC already made on the town. That option was eliminated by the settlement agreement, which requires the city not to oppose the People’s Park project.

There’s a difference, however, between non-opposition and advocacy. Going above and beyond the settlement agreement’s stipulation, the Arreguín council vigorously supported the university. In April 2023, after a state appeals court had backed lawsuits from Make UC a Good Neighbor and the People’s Park Historic Advocacy Group that opposed the project, the council submitted an amicus brief asking the state Supreme Court to grant UC’s petition for review. Authored by City Attorney Fatimah Faiz Brown, the brief stated that as “the home of UC Berkeley,….the City is keenly aware of the need for additional, on-campus student housing. The lack of such student housing at UC Berkeley” has not only disadvantaged UC Berkeley students but has “also place[d] significant strain on the City’s housing market for other residents, increasing housing prices and displacing long-time members of the community.” It didn’t note the campus’s perennial failure to house its students, nor did it comment on the university’s ceaseless expansion.

Noise generated by students was integral to the lawsuit. In August, the legislature passed Buffy Wicks’ AB 1307, which eliminated noised generated by occupants or guests of a housing project as a significant impact under CEQA. The bill also included provisions that relieved UC of considering alternative sites for the housing proposed for People’s Park. On September 9, Governor Newsom signed the bill into law. The California Supreme Court was still poised to hear the case.

On September 19, the city council unanimously approved on consent (no deliberation) (Item 18) the submission to the Supreme Court of a second amicus brief in support of the university.

Robinson: democracy at risk

This is the background against which Rigel Robinson’s resume, especially his cheerleading for the university, should be viewed. To obscure or simply omit that context, as the press typically did, is to accredit his sneering description of Berkeley—more precisely, the pre-Robinson Berkeley—as “‘a city notorious for its resistance to new growth. The Nimby capital of the world.’”

When they wrote that the People’s Park housing project was fought by “so-called ‘left Nimbys,’ who oppose new development on the grounds that it hurts lower-income and marginalized people,” Business Insider reporters Sheffey and Relman alluded to the biggest crack in Yimbyism’s theoretical foundation. But they packaged that reference in Yimby rhetoric (“left Nimby”) and then discredited it.

Worse yet, they let Robinson get away with outrageous claims about opposition to the People’s Park project.

“We knew that when the park was closed, it would be an intense and fraught moment for our community,” Robinson told Business Insider. “But when people employ tactics like harassment and stalking and threats to try to subvert the will of the people and the votes and directions that our democratically elected city council has made, I think that creates a problem.”

Harassment, stalking, and threats—Robinson was presumably referring to the death threats he had allegedly received—are worse than problematic; they’re unacceptable.

But Robinson’s sly equation of the pushback against himself with the opposition to the People’s Park housing at large was spurious. He could have distinguished the inexcusable opposition he allegedly encountered from legitimate forms of protest. Instead, he conflated the two.

Even worse was his tacit denunciation of the larger opposition to the park housing project as anti-democratic because it contested actions taken by the City council. No longer was it just his mental health or UC expansion or the Yimby agenda that were at risk; now the stake was democracy itself.

Whether the actions of a democratically elected body inherently express the will of the people is debatable. What’s certain is that dissent from such actions, including, up to a point, unruly dissent, is integral to a democratic politics. The challenge is to identify that point without stifling democracy.

Sheffey and Relman should have questioned Robinson’s dubious claims. If their failure to do so had been unusual, it would merely be troubling. But because it replayed the violence-against-public-officials-has-been-normalized narrative that had been broadcast by other reporters, their reticence wasn’t just troubling; it was dangerous. An authoritarian official could cite that narrative to justify a crackdown on mere insubordination.

As the fifth and final installment of this mayoral series will show, two weeks before Election Day, something very like this happened in Berkeley and got an approving nod from mayoral candidate Adena Ishii.