It was a late night in 1987, and John Birdsall was wracking his brains about how baking pies could be queer.

A full-time restaurant cook and writer for late, lamented gay newspaper the San Francisco Sentinel at the time, Birdsall wanted to bring two major aspects of his life—cookery and queerness—together. “Then, lingering outside the Stud one night,” he writes in new book What is Queer Food? How We Served a Revolution, “I noticed one of the bar’s window boxes on busy traffic-strafed Folsom Street had this sprawling rose geranium plant that was unexpectedly thriving. I thought, holy shit, this is the experience of being gay in a time of AIDS! This neglected hanger-on, devoid of flowers, on an unforgiving block, invisibly harboring an essence of roses.”

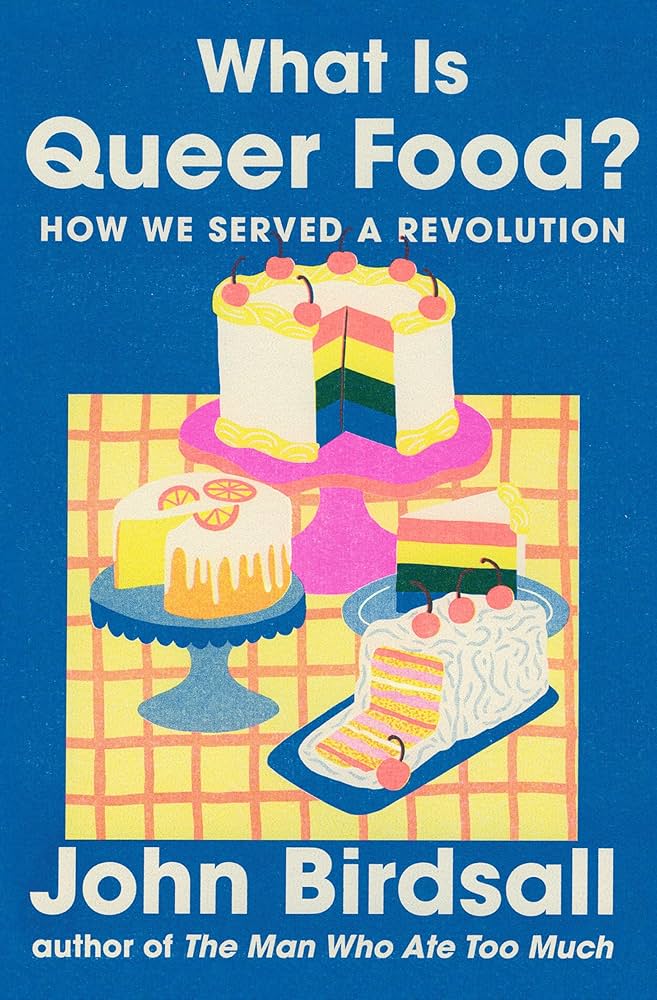

Birdsall harvested some leaves and small branches, buried them in sugar to infuse their scent, and used it to sweeten an apple pie—”transform it with this lush, sweet perfume: a pie of rebellious survival, of pleasure as defiance.” It was his personal recipe of gay inspiration, queer improvisation, deviant joy. Queer Food centers itself around such zesty apostasies, within a historical framework of the development of contemporary cooking—its legendary pioneers, cookbooks, and popular triumphs. That history, beginning in the late 19th century, overlaps with the development of the modern sexological concept of homosexuality, and Birdsall finds many astonishing connections between the two.

A “cast of sissies, freaks, and exiles” like young Harry Baker with his delicate early 20th century chiffon cake, promiscuous 1940s cookbook-memoirist Harry Smith, effeminate food critic and author Craig Claiborne, and genius SF filmmaker-turned-restauranteur Edith Eng form the historical backbone of the book. Birdsall, whose last endeavour (besides launching a terrific newsletter) was a monumental biography of closet case James Beard, includes little of him here, but Beard’s spirit hovers over the proceedings. And of course there’s Alice B. Toklas and her indispensable literary “Cook Book,” which contains one of my favorite dishy anecdotes: When presented with a spinach soufflé, Pablo Picasso inscrutably called it “a cruel enigma.”

I spoke with Birdsall via Zoom form his promotional book tour stop in New York—he’ll be here at Omnivore Books in San Francisco on Sun/22, Bombera in Oakland on Mon/23, and Napa Bookmine on Tue/24.

48 HILLS I love the story of your rose geranium epiphany outside the Stud. Later in the book, you talk about how hard it was to get chefs and restaurant workers to talk about being queer, until around 2011 when you were writing for Lucky Peach magazine, and suddenly people couldn’t stop talking about it. Can I kick this interview off with an anecdote? Right around 2011, my husband and I were eating at Nopa and the waiter offered us the gayest desert platter of all time: sharlyn melon, lavender cookies, and rose geranium sorbet. It sounded like a trio of drag queens who would be performing at the Stud! Surely there was someone queer back in that kitchen.

JOHN BIRDSALL That sounds exactly like something that would happen at the Stud back then. [Laughs.]

48 HILLS You’re coming off this huge biography of James Beard, was What Is Queer Food? germinating while you dove into that incredibly influential figure’s life?

JOHN BIRDSALL This book definitely feels like a culmination of things that I was thinking about while writing the Beard book—and that, having written the book I felt like there was more to say. Writing about Beard was a useful way into thinking about how what the culture of queer food in the 20th century might have been, and of course Beard embodied a lot of that, but there was still so much that I couldn’t express about that through through Beard himself. I felt like I needed to take a few steps back, or maybe several steps back, and really diversify the figures of the stories that I was telling. I very much wanted to also capture the scope of rise of queer subjectivity and the queer civil rights movement in the 20th century.

I start this book with Harry Baker as a boy in the 1890s, 13-year-old Harry Baker wanting to make cakes. That’s almost the exact moment when the word “homosexual” appears in the United States for the first time in print. That was the scope I was after. To entwine those histories and tell a fuller story.

48 HILLS Your writing about Esther Eng was revelatory to me, I had no idea about this incredible openly lesbian, feminist filmmaker who grew up in San Francisco amid the Cantonese opera scene—while Americanized Chinese food like chop suey and fortune cookies were developing and being popularized here—made these women-centered films in Hong Kong and here in the 1930s and ’40s, and ended up owning restaurants in Manhattan.

JOHN BIRDSALL I felt chagrined that I hadn’t known much of her history when I started the book, but most of her films were destroyed or lost. She had such a striking history and much of it is gone—we wouldn’t know a lot of it if someone hadn’t discovered a cache of her photo albums in a dumpster in SoMa in 2006! What we do know of her, she truly transcended so many boundaries. Even her roots in Chinese opera have queer ripples, since it influenced generations of queer composers like John Cage and Lou Harrison. It was enlightening talking to San Francisco State queer Asian history scholar Amy Sueyoshi about Esther and that time. She was like, Oh yeah, Chinese opera was hella queer.

48 HILLS I love that Craig Claiborne reviewed her restaurants. He’s a central figure in this book—and in my own gay life smorgasbord. I remember when I first started being invited into gay men’s homes in the 1980s and almost every one of them had a Craig Claiborne book in them. He’s the person I most associate with refined dinner parties and gay socialization before the Internet …

JOHN BIRDSALL I wanted at heart to write this optimistic book, and in a way Craig’s story is that—he was so terribly bullied as a boy and then rose to transform the tastes of the nation regarding food, at least white peoples’ taste, embracing diverse cuisines and becoming a household name. But in a way he’s the most tragic figure here in that, unlike Esther, he couldn’t quite come out and live the way he wanted to—or rather, he embodied this ambivalent energy that I think many gay men of a certain age can relate to. It felt impossible for someone like him in the 1950s when he was growing in his career. So he adds this kind of melancholy counterpoint to the rest of the book.

48 HILLS Speaking of ambivalent energies, I think one of the most shocking things to read about in the book was Julia Child’s homophobia, how she fantasized about the “de-fagification” of food writing and lamented that there were so many gay men, whom she equated with pedophiles, in her industry. I mean, my young gay body was electrified seeing her making fancy French food on TV and trilling out words like “velouté” and “Camembert”!

JOHN BIRDSALL Julia is difficult to talk about, partly because she is so huge. The food historian Laura Shapiro has been great about discussing Julia and her husband Paul’s homophobia, but in the last, several years there’s been a new wave of Julia love and appreciation, certainly in food culture. She did so much to expand the boundaries for women, especially.

But the fact that we don’t know any sort of difficult or conflicting information about Julia, I think, is an indictment of food media itself. That is what I wanted to do with the Beard biography, to tell difficult parts of the story of someone who the world sees as admirable in many ways, but not shy away from the darker parts of Beard’s personality, like the sexual abuse of his assistants.

With Julia, she’s such a fantasy figure, but she was also just weird. There’s a famous New Yorker profile of her from, I think, 1972, and she’s in San Francisco to give a talk but has to save her voice. So she goes with the writer to a restaurant in Chinatown and refuses to speak, only writes things on napkins. When one dish comes out, she writes on the napkin to the reporter, “Tastes like cat puke.”

48 HILLS Another grand figure you tackle is Alice B. Toklas, but fortunately she was very comfortable with queerness. I love the Picaso anecdote about the “cruel enigma” of her spinach soufflé that you include in the book. Certainly her Alice B. Toklas Cook Book set a stratospheric bar for literary cookbooks, and also sales, in the mid-20th century.

JOHN BIRDSALL There is this myth of Alice sitting quietly in the background of Gertrude Stein’s powerhouse personality and achievements, but she was an intense collaborator of Gertrude’s, not just her typist. I’ve always been an advocate of giving cookbooks in-depth textual readings. Some people think the Cook Book was just dashed off to make a buck, full of celebrity name-dropping. But as I point out in my book, she completely inverted the normal conventions of the cookbook—one that persists on blogs to this day—and just put the recipe first, right up top. Kind of no nonsense.

And even through she said there was no need for an autobiography because Gertrude had already written it [The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas], there is evidence that this was a serious literary endeavor for her, in both form and contents. She’s not doing showy things with it, like Marinetti’s Futurist Cookbook, but making it her own in a very particular and successful way.

48 HILLS We live in a moment when “queer food” seems transcendent—gay Black Jewish Southern cookbook author Michael W. Twitty winning the James Beard Award is just one example. Or maybe that’s in the past and we are facing a whole different moment of back-in-the-closet cuisine….

JOHN BIRDSALL I don’t know if that moment has ended. In the beginning of May, the big Queer Food Conference was happening in Boston all week long. There are big queer dinners organized across the country, like 400 people, and they sell out. There’s still a ton of community being built around queer food and gathering together. It has an intensified resonance now, because of the political moment. But one of the themes of the book is how we form our own communities through food—in kitchens, at dinner parties, in special restaurants—and how we use food cooking as an expressive element of our identities. How we express our gender and sexual identities through these acts of making and sharing.

Even just making my special chicken dish for someone, how that’s a connection on both sides of the plate. It’s been a long hard road, and maybe “queer food” sounds glib at this moment, but this is still an incredibly fertile moment of queer expressiveness and creation through cooking. I hope through the book, I give that some historical context, and reason for celebration.

You can purchase What is Queer Food? at your local independent bookstore, Bookshop.org, or here.