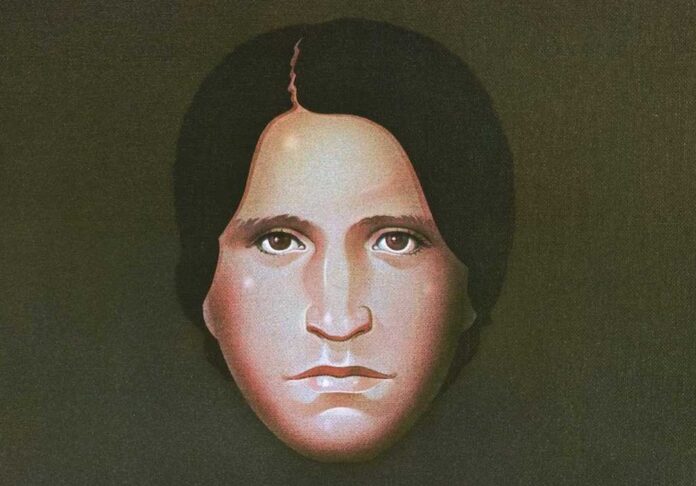

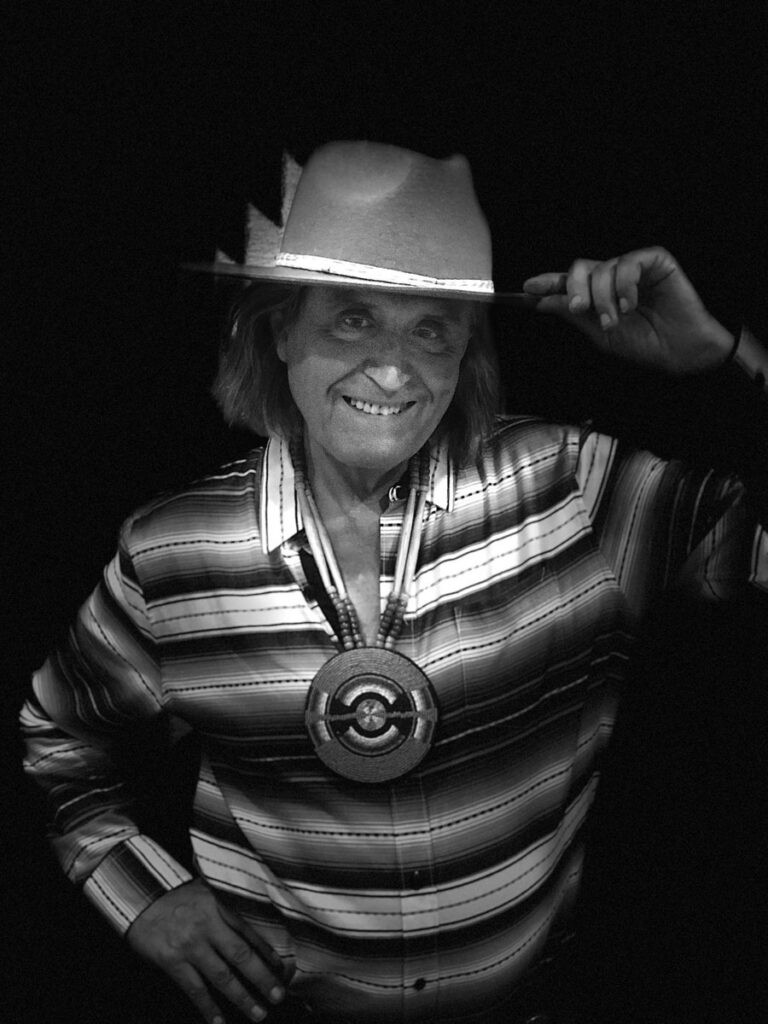

In 1973, an album called En Medio by a young pianist named Garrett Saracho appeared on ABC/Impulse Records—and, seemingly, disappeared long after. The Los Angeleno of Apache and Mexican descent scored a deal on the basis of his connections in the ‘70s jazz milieu, but the lengthy Latin funkscapes on En Medio apparently weren’t what his label wanted, and he subsequently pursued a career working behind the scenes in the film industry while gigging with his cousins Pat and Lolly Vegas in Redbone, the Native American rock band best-known for the 1974 smash “Come and Get Your Love.”

Saracho figured his work had been forgotten until he received a call from a young San Franciscan named Wolfgang Mowrey, who’d found a copy of the record and was wondering if he was still gigging. Mowrey now manages Saracho and connected him with producer Adrian Younge to play on the 15th installment of his Jazz is Dead series of multigenerational collaborations. It represents Saracho’s first appearance on record as a featured player in almost 50 years, and he seems to have plenty more in the tank.

Saracho plays two dates in the Bay Area this week: one with Couchdate in Oakland on Wed/11, and another semi-secret show in San Francisco on Fri/13. In advance of these events, 48 Hills caught up with Saracho and discussed his return to the studio and stage.

48 HILLS You lived in San Francisco in the early 1970s. When was the last time you were here?

GARRETT SARACHO 48 years.

48 HILLS You haven’t visited since you lived here?

GARRETT SARACHO I came here 32 years ago and I did the Alcatraz Occupation reunion with all the natives. I didn’t come to the city. I just went straight to the island. I was invited to perform with Redbone. I never realized how big San Francisco was until I got on the island. That was the last time. It’s like a time warp. I’ve been telling some people I feel like I’ve been asleep and I woke up and now suddenly I’m back here again.

48 HILLS Tell me about the band you’ll be playing with for these shows in the Bay Area.

GARRETT SARACHO Never met them. I don’t know the guys.

48 HILLS So you’re meeting them for the first time…

GARRETT SARACHO Right after I talk to you. We’re gonna do a rehearsal and then we do the performance tomorrow.

48 HILLS How does that work?

GARRETT SARACHO I’ll let you know after tomorrow. I’ll keep you posted.

48 HILLS What was it like making the first record under your name in almost 50 years.

GARRETT SARACHO I think the best place to start is how I met Wolfgang, because he just called me out of the blue. I don’t even know how, he just called me up and he asked me if I was who I was. I told him yes, and he said: “You know, I play your album. It’s a wonderful album.” I said, “Which album is that? And he said, “the En Medio album, we love it here at the studio, and everybody’s been calling me and letting me know about it and everything, and we really like it.”

So he came, a photographer came over and we did about three or four magazine articles and then did some Zoom calls to London and France. And then he said, “I met this guy [Adrian Younge], he’s doing an album and we’d like to have you come on board to participate.” So I got the information and I went over there and knocked it out in about two or three days. That was it. They’re not my compositions. I was an invited guest. It’s Adrian’s music.

48 HILLS Are you planning on recording any of your own work in the future?

GARRETT SARACHO Yes, I am. I’m planning on doing a lot of things in the future. I got a musical revue, a musical play and a screenplay all based on the same concept. The screenplay is entitled The Boys From North Broadway.

48 HILLS How long have you been working on this?

GARRETT SARACHO For 48 years. I started listening to some of the conversations that my dad would tell me about the old neighborhood, which was basically before Chinatown, and my uncle, who grew up in the same neighborhood and wound up going into professional boxing. He trained three world boxing champions. He was popular in San Francisco and San Jose and Sacramento. My father was a designer. He worked on aerospace defense. He worked on the EPCOT projector, worked on the Apache helicopter helmet, worked on the B-1 bomber, worked on the Tomahawk missile guided system. He worked on album covers for Capitol Records.

When they were growing up, they would tell me stories and I never forgot them, and I started to put some together and I eventually built my screenplay and my musical revue, and I’m writing the book right now. I have music already recorded, an album called Dare to Dream, but I never released it. I wasn’t interested in selling it. I did it for posterity. I’ll be performing about three or four of the compositions this week.

48 HILLS When you made your first album En Medio, ABC Records refused to invest in more pressings, supposedly due to the 1973 oil embargo. Do you believe that?

GARRETT SARACHO I was under the impression that it was because of the oil embargo, but I didn’t know anything about it until l did a performance at Cal State Los Angeles. I got a phone call one day. This guy from KABC TV called me up and he said, “your name was mentioned, and we were interested to know if you would be interested in doing a performance here at Cal State LA. You’d be opening up for Jose Feliciano and Vikki Carr.” So I got there and there were already a bunch of local bands. A cattle call is what it was, essentially.

So I got up and I played for about 30 minutes while the people were coming in. When we finished, I got a great ovation, and I walked off the stage and I was tired and sweaty and just wanted to get home and get the hell out of there, and all of a sudden here comes my cousin with this big guy, about 6’2”, white shirt, tie, sleeves rolled up, he walks up to me and says, “you guys belong in Berlin, you belong in Paris.” I thought he was gonna tell me to get my van off the campus, but it was Ben Barkin, vice president of Schlitz malt liquor. He says, “When I get back to Milwaukee, I want you to call me.”

So I called him up and he says, “I’m gonna give you a number to call. He’s in New York, his name is [jazz promoter] George Wein. You know George?” I said, “Yeah, that’s God.” So when I called him, he said, “I’m gonna book you in London, I’m gonna book you in Paris, and I’m gonna book you in Montreal. We’ll start you off. How do you like that? And I said, “sight unseen?” He says, “Ben recommended you. You gotta go with the flow here, so you’re welcome aboard. I just need your number to call your record company.”

And when he called the record company, they told him that they weren’t buying my radio time. And that’s when I found out it wasn’t the oil embargo.

48 HILLS Why do you think they signed you in the first place?

GARRETT SARACHO I have no idea. I think it was because Lee Young was there. He left to Motown, and then when Ed Michel came aboard they started doing a number on all the artists. If they would’ve just bought my radio time, I would’ve taken off because I had all kinds of musicians that I was gonna get. I played with great musicians. I grew up with B.B. Dickerson, that’s the bass player from War. He passed away a couple years ago. I was hanging with Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock. Herbie Hancock was the one that introduced me to Wayne and Jaco [Pastorius]. I never really played with any of them. I just sat there and absorbed everything and learned a lot.

48 HILLS After En Medio, you moved into the film industry. Tell me about that transition.

GARRETT SARACHO I left music for about 11 or 12 years after ABC Records let me go. I just didn’t want to go back to it. It was just too painful. I was in the labor department, then I was in special effects. I ran the tool shop at Universal. I was going to school and I was working, so none of them ever knew that. The film industry people told me, “you’re not gonna go to school. You can’t go to school and work.” I did. I worked in the summer and in the fall, and then in the spring and the winter I would go to school.

We worked on a bunch of different TV shows. We worked on Magnum, worked on Airwolf, worked on The Hulk, Beretta, basically all the shows that were at Universal and Warner Bros. and 20th Century Fox. Eventually I got an opportunity from a guy I had met in the editorial department to work in editorial. So I came in on board and I worked there for a couple years.

48 HILLS Was the film industry less painful than the music industry?

GARRETT SARACHO I would say it was a little easier politically until the end, and then this guy who hired me told me he had to let me go for no reason at all. He just let me go. And when I asked him for a recommendation, he wouldn’t give me one, and I couldn’t understand why, because I wanted to go to another studio and work. And in that industry, in the editorial department, all you need is a phone call. It’s just like what happened at ABC. The underlying theme is probably that I didn’t have representation like I should have. When you have representation, it’s different. It’s kind of like that saying: Anybody who represents themselves in a court of law has a fool for a client.

48 HILLS What if you’d had Wolfgang back then?

GARRETT SARACHO It probably would’ve been great. In the time that we’ve known each other, we’ve done pretty good. It’s been a good relationship.

48 HILLS Boxing is a major theme in your life. Do you see any connection between boxing and your artistic practice?

GARRETT SARACHO Boxing is a disciplinary type of sport, and you have to work every day. It’s almost similar to ballet, you know? When I was a kid, I was about three or four years old when I first walked into a boxing gym. The first thing you hear is that speed bag. And you hear the jump rope and then you hear the voices and the guys are in the ring and they’re doing it like matadors or a ballet company. The whole structure of boxing is built around focusing on the individual to get in touch with their competitive nature so they can compete in the world of boxing.

And my uncle used to always tell me when I’d walk in, “you sit on the stool, you keep your mouth shut, don’t say nothing. Just watch people.” And that’s what I did. Eventually I met a lot of people. I met a boxer named Pete Gonzalez. He was the one that wound up sparring with Paul Newman in Somebody Up There Likes Me. And I used to see a young Paul Newman come out of the limousine and walk up to the sound stage. I saw a lot of interesting people when I was a kid, and I just always wondered what these people were all about.

And in the boxing gym, all you heard was jazz. No rock. It was all jazz, Latin jazz and stuff like that. Boxing and jazz were always hand in hand. Miles used to talk about boxing all the time. Joe Zawinul talked about boxing all the time.

48 HILLS I’ve heard of so many musicians in all genres that are inspired by boxing. There seems to be a kind of poetry in the sport.

GARRETT SARACHO As I was getting older, I said to my uncle, “you know, I’d like to box,” and he goes, “this is not for you.” I was kind of heartbroken. He said: “Stick with those Black musicians. They’ll live longer, they’ll last longer.” And reluctantly, I said OK. And here I am today.