The prospect of the next four years fills many of us with “deep apprehension and gloomy foreboding,” as Joel McCrea’s butler tells him near the start of Preston Sturges’ great 1941 Sullivan’s Travels. Nonetheless, just as “the entire expedition” that character warned against was fecklessly entered into anyway, so we’re gonna find out what happens when an angry felon who no longer feels bound by a nation’s laws gets put in charge of said nation (again). Perhaps the mood of the moment might best be described as “bracing for impact.” Possibly helping in the transition from shock and denial to resistance are two well-timed new local film retrospectives.

First up is “Masc II: Mascs plus Muchachas,” a followup to guest curator Jenni Olson’s largely sold-out series at Berkeley’s BAMPFA a year ago. The seven features here sprawl across the globe and eight decades. But all provide further representation for “Butch Dykes, Trans Men, and Gender Nonconforming Heroes in Cinema,” or AFAB (assigned-female-at-birth) “masculine” persons. Needless to say, this glimpse of diversity onscreen is particularly relevant at a moment when so many Americans think one of society’s most pressing issues is who gets to use the women’s bathroom. (Where, I might add, privacy is accentuated by the existence of stalls). So many Americans… who’ve probably never met a transperson in their life, but have been whipped into a fearful frenzy for the sake of pure, putrid political opportunism.

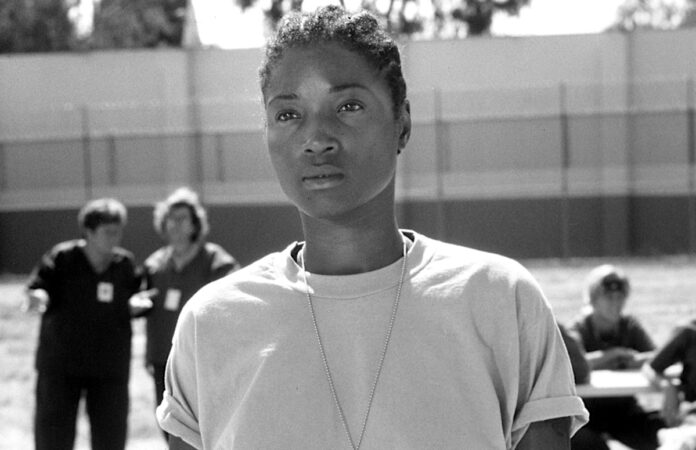

The features this time around are as recent as Spanish academic Paul B. Preciado’s 2023 French feature Orlando, My Political Biography (kicking off the series this Fri/17), a mix of interview-based documentary and fancy-dress phantasmagoria probing the ever-expanding frontiers of gender identity. There are two disquietingly powerful 21st century. narratives from Black writer-directors, Cheryl Dunye’s prison-set 2001 mother-daughter drama Stranger Inside and Dee Rees’ 2011 tough teen coming-out tale Pariah.

Three infrequently-revived international films from the 1980s remain boundary-pushing. Sergio Toledo’s 1986 Vera fictionalizes the life ofAnderson Bigode Herzer, a trans male Brazilian poet who took his own life at age 20. The same year’s Something Special aka Willy/Milly is a wacky US independent comedy from Paul Schneider that feels like an After School Special or Freaky Friday imitation, but a bit more daring. Its heroine (Pamela Seagall) is a 14-year-old suburban tomboy whose “deepest darkest heart’s desire” is to be an actual boy. Having that wish magically granted, however, turns out to be a very mixed blessing.

The oldest film here is a real rarity that was only recently rediscovered and restored. Muchachas de Uniforme is a 1951 remake of the Weimar Republic classic Madchen in Uniform made 20 years prior. While Leontine Sagan’s original version (which was itself based on a play) served as an indictment of neo-Nazi Prussian martial-style discipline at a girls’ boarding school, here a different kind of authoritarianism is at play: Religious fanaticism and hypocrisy at a similar educational institution run by nuns.

An orphaned new arrival (Irasema Dilian) directs her emotional neediness towards a kind secular teacher (Marga Lopez), though their alliance draws gossip and scandal. Surprisingly overt for its era in dealing with latent lesbian desires, this film by the prolific Alfredo B. Crevenna was duly objected to by the Catholic Church, and never released in the US. But it’s a peak example of studio craftsmanship from Mexican cinema’s “golden age,” embracing melodrama yet too artful to descend into camp.

All screenings in the series, which runs through February 23, will have post-screening discussions with Olson, filmmakers, academic specialists, and other guests. Full info is here.

S.F.’s Roxie Theater remains alive and well, though some viewers still miss the programming of Elliot Lavine, who pioneered its noir and pre-Code series among other highlights. He moved to the Pacific Northwest a few years ago, but will be back this weekend for The Resistance Film Festival, billed as “A Cinematic Salvo Blueprinting American Democracy Restored.” The four vintage features on tap during the two-day event Sat/18-Sun/19 all dramatize the fight against fascism as it was happening during World War II. Of course they offer some of the sentimental and simplifying elements our government required of Hollywood during that period. But they still pack more of a punch than you might expect.

First and most fabled among them is Michael Curtiz’s 1942 Casablanca, a famously troubled production whose enormous, lasting success surprised all its participants. Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, and Paul Henreid play three sides of a refugee romantic triangle in the titular city, torn by loyalties even stronger than love. The same year Ernst Lubitsch directed a very different movie about sabotaging Axis forces—To Be Or Not To Be, in which Jack Benny and Carole Lombard play a married pair of vainglorious stage actors whose skills end up deployed fooling Nazi officials in occupied Warsaw. This risky yet gold-plated farce is sadly emembered primarily as Lombard’s swan song, since she died in a plane crash on the way home from a war-bond rally one month before its release.

Well-regarded if not quite considered in those films’ league is Frank Borzage’s The Mortal Storm, which arrived in 1940 as one of Hollywood’s first major statements against German fascism. Margaret Sullavan, James Stewart and a host of future stars play members and intimates of a respected professor’s family living near the German-Austrian border. But once Hitler assumes power in 1933, their fortunes take a steep downward turn, leading to political pressure, ostracizing and tragedy.

Similarly addressing the phenomenon of ordinary people seduced into or resisting totalitarianism is the find of the series, Andre de Toth’s 1944 None Shall Escape. Taking place in “the future,” after an unconditional Nazi surrender that was still just wishful thinking when the film was made, it starts unpromisingly as a courtroom drama with a high-ranking Nazi officer on trial for war crimes. Charged with “wanton extermination of human life,” among other things, Wilhelm Grimm (Alexander Knox) sneeringly pleads innocence, and insists on defending himself.

But flashbacks reaching back a quarter-century soon make his path look indefensible. A German who’d taught school in a Polish village, he came back embittered and lamed from WWI service, so viciously changed that the fiancee who’d faithfully waited for him (Marsha Hunt) refused his hand. That only fuels his wrath, triggering rash acts that get him driven out of town. He returns years later—for vengeance, as a Nazi commander now in a position to persecute those he thinks persecuted him.

Wilhelm is admittedly something of a villainous cliche—we don’t grasp how an ordinary citizen might get indoctrinated to Nazism, because when we first meet him he’s already well on his way to being loathsome. He’s a cad, a liar, a bully and sneak, capable of rape and murder. But while None Shall Escape was just a Columbia Pictures “B” movie that attracted relatively little notice (though it did get a single “Best Story” Oscar nomination), it seems shockingly prescient now for addressing a number of issues that weren’t widely acknowledged until war’s end. It shows starving villagers being urged to “smile, smile, smile” at the staged generosity of their occupiers for German propaganda cameras, as happened in real life. It is very up-front about Nazi brutalization of the Jews. There’s a startling sequence when those being herded into trains—aware they’ll never survive their destination—rebel, and get mowed down by German soldiers’ machine guns.

This is strong meat, especially for a modest film shot in mid-1943. Its anticipation of the Nuremberg trials is also pretty jaw-dropping. While this was surely not the kind of feel-good entertainment most Americans wanted to see in 1944 (when the year’s biggest hits were musicals Going My Way and Meet Me In St. Louis), None Shall Escape retains a lot of punch now—as well as, dismayingly, no lack of relevance.

For info on the full Resistance Film Festival program and schedule, go here.

While we don’t have space to dwell on them at length, there are also some new releases of note this Fri/17. Also at the Roxie, there’s Werner Herzog’s latest documentary Theater of Thought. It applies his usual quirky, questioning sensibility to a survey of developments and ethical quandaries on the frontiers of neuroscience, featuring input from many Bay Area experts.

The same venue is also opening Maura Delpero’s Vermiglio, a quiet epic in the vein of the Taviani Brothers set in an Italian Alps hamlet during WW2. Its residents are divided about accepting two deserters from military service, though one eventually marries into the local “professore’s” large family. It’s a stately, scenically beautiful film, with some sharp insights into a remote time and place. But it’s also slow and not terribly involving, the performers held to a kind of neo-realist naturalism that doesn’t allow for much charisma. Others have found Vermiglio hypnotic, however, so do try your luck.

Last but not at all least, there’s Swiss director Tim Fehlbaum’s new September 5, which revisits events that have often been dramatized before: The “Munich massacre” of 1972 when Palestinian militant organization Black September took members of the Israeli Olympics team hostage. The standoff (which ended in sixteen deaths during a failed rescue attempt) has been portrayed onscreen in various ways, including the espionage aftermath depicted as a thriller in 2005’s Munich, not one of Steven Spielberg’s better films. But this docudrama has a fresh angle, limiting itself to the response of the ABC Sports crew that found itself reporting “the first terrorist act broadcast live around the world.”

Peter Sarsgaard, John Magaro, Ben Chaplin, and Leonie Benesch (from The Teacher’s Lounge, as a local translator) play network crew frantically making big decisions once their routine coverage of athletic competitions turns into a breaking international news story. As Sarsgaard’s executive says, “It’s not about politics, it’s about emotions”—an approach describing not just these telecasters’ strategies, but that of the film itself. A taut 94 minutes among so many more bloated current awards-bait features, September 5 is perhaps neither starry or controversial enough to rival them for attention. But opening locally this Fri/17 as part of its gradual national release, it’s certainly one of the best mainstream features in theaters now.