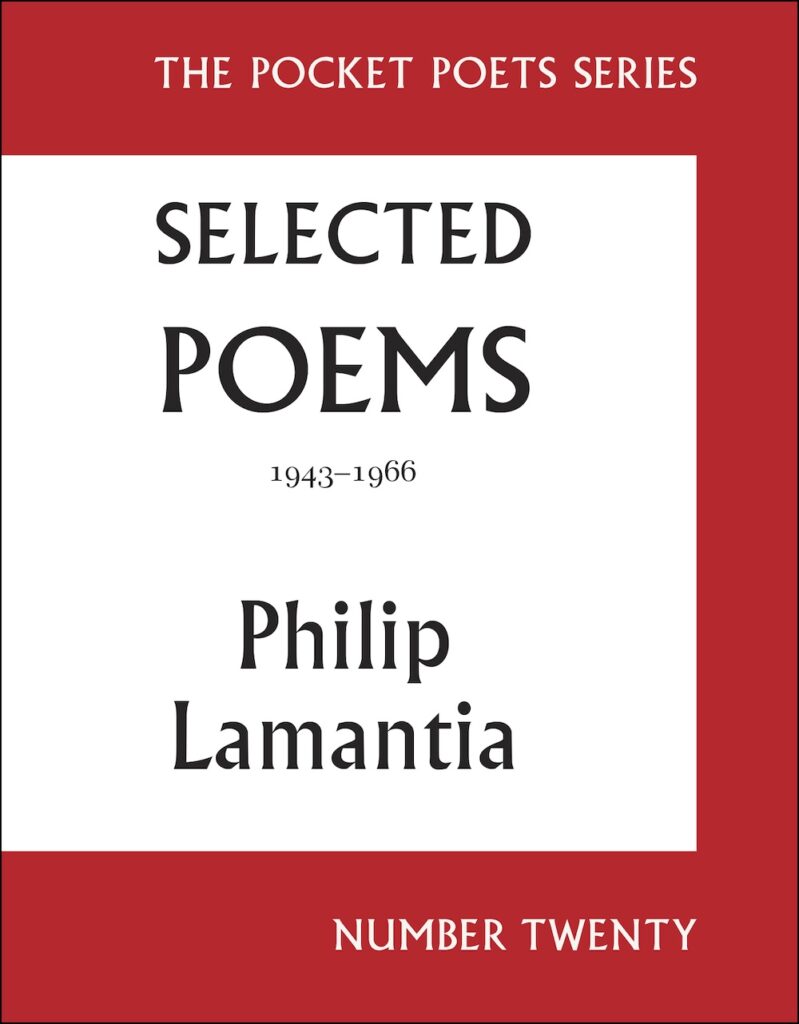

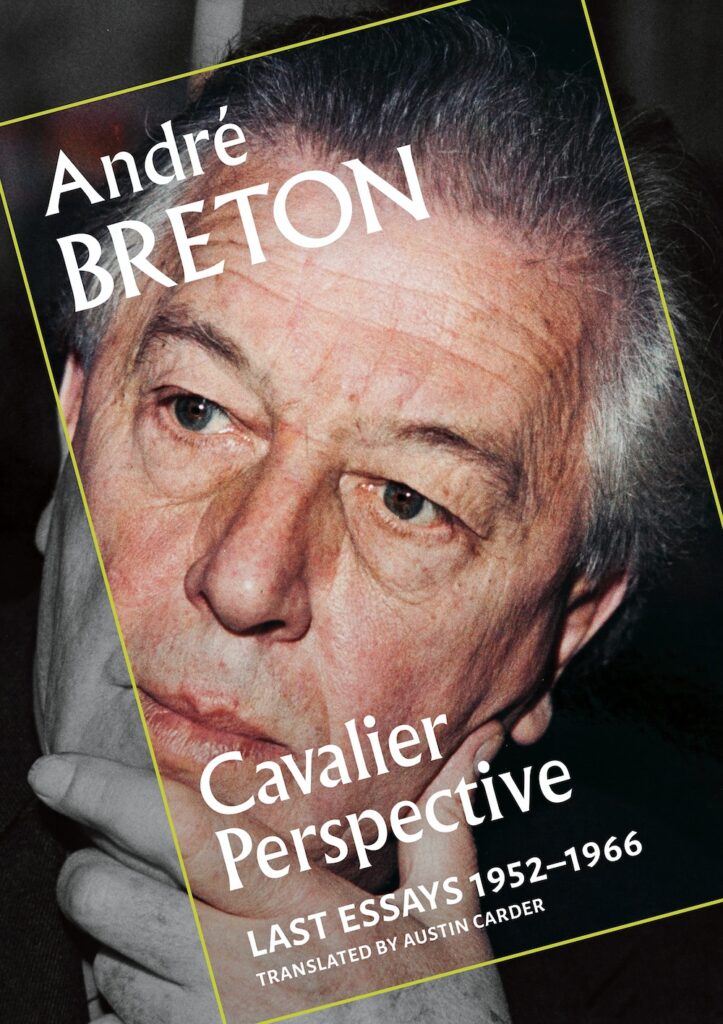

In the last six months, City Lights poetry editor Garrett Caples has ushered new editions of two surrealist tomes to market, an act rife with literary significance. In February, a reissue of Selected Poems of Philip Lamantia, 1943-1966: Pocket Poets No. 20, originally published in 1967. And on August 26, the first English translation of André Breton’s final book in Cavalier Perspective: Last Essays, 1952-1966, translated by Austin Carder from the French version originally published in 1970—and to be fêted at City Lights in a Thu/11 launch party.

Since 2004, Caples has been explored the inextricable connections between the two surrealist luminaries: Breton, a founder and theoretician of the original surrealist movement, and Lamantia, a delighted devotee who decamped to New York City at the age of 16 to receive an audience with an exiled Breton in 1944. Furthermore, Caples contends that the two books serve to elegantly bookmark an important transitionary period in Surrealism’s sphere of influence, and create a conversation between two distinctive schools: the old guard Surrealism of post-WWI Europe of which Breton was a leader, and the rise of a later, distinctly American version from 1966 on.

I sat down with Caples shortly before the publication of the translated Cavalier Perspective to chat about its place in the Surrealist canon, the conversation between it and this year’s earlier re-issue of Selected Poems of Philip Lamantia, and how Surrealism has always offered a framework for liberation.

Interview has been edited for brevity and clarity

48HILLS So, one of the main focuses of what we’re talking about are ways to tie these two publications together under a surrealist umbrella, shall we say.

GARRETT CAPLES 1966 is like a pivotal year for both these books because it’s when Breton dies, so it’s the sort of cap on this thing. Philip’s book comes out in ‘67, but its selected poems 1943 to 1966 […] it’s the pivotal moment between original Surrealism coming to its historical close. You could say the original group lasts from the late Teens—like coming out of the Paris Dada into Paris Surrealism—and ends in ’69, three years after Breton died.

1966 is also when the Chicago surrealists kind of get going. The Rosemonts (founders of the Chicago Surrealists) were out in Paris very close to Breton’s death. Like, they had plans where they were invited to go over to his studio to hang out and really talk, but he was just too sick. But they met all the latter-day Surrealists who pop up in in this book, like Jean Benoît who [performed] Exécution Du Testament Du Marquis De Sade, where he branded himself with the word “Sade” over his heart. His wife was Mimi Parent. The Chicago surrealists met all those people, and they came back and set up shop.

There was something to it, obviously, because Philip made common cause with them [and] because his connection to Surrealism and Breton was so indisputable and authentic and direct, he gave them a lot of the heft they had as being taken seriously as representatives of Surrealism. But on the other hand, I mean, he sought them out. So the Chicago Surrealists, they did some good stuff in terms of being like, a great kind of network. They were great at finding people [and] pulling them back into the orbit.

48HILLS Something I got from your forward was the idea that what Breton is doing when he’s writing about Surrealism, when he talks about Surrealism, when he’s investigating Surrealism, is that Surrealism exists. Outside of our perception, is it its own thing and he’s naming it, or discovering it, or wrestling with it? I wonder if you want to talk a little bit more about that.

GARRETT CAPLES Well, it’s what distinguishes Surrealism from most other avant-garde movements, in the sense that avant-garde movements tend to be prescriptive, and Surrealism was much more—as you say, it was something outside of them that they were looking to discover. Surrealism is trying to define a particular realm of human experience, and that’s kind of what makes it unique. Certainly among the modernist avant-garde—Futurism or whatever—where they’re like, “don’t do this, do this.” And there’s plenty of that in Surrealism, but it’s more like they’re trying to tease out the implications of what they’re investigating, and our investigation would indicate “do this and do that.” [laughs]

48HILLS An article I read in Artforum that was about European artists and Surrealists in exile New York, made mention of the fact that the European Surrealists hung out over here and the Americans, whatever they were, were over here, and there wasn’t a lot of crossover. I kind of got the impression there were some hurt feelings on both sides.

GARRETT CAPLES Well, I mean, think of it this way, It’s like Breton comes to New York, and people are very interested in Surrealism already by the time he arrives, because Dali had been over before. And Dali was great at generating attention.

So then naturally, there are a lot of people who are interested in it. And they would like to make common cause with Breton. But Breton is pretty standoffish, and the one poet that he said, “this is a Surrealist poet” was Lamantia, who was 15 years old. Picture the consternation that this must have caused, you know, all these adult poets who wanted to be Surrealists, that Breton wouldn’t countenance bestowing that on them, but does bestow it on Philip. It’s very symbolic of Breton’s whole sojourn in America, because he never really did the politic thing. [But] he could have had it a lot of easier if he was a little more flexible.

One thing I make a big deal about in the introduction because it was mystifying to me how people talk about Breton. They emphasize his power and authority and stuff, which he certainly had. But it was all just him and his word, you know? He didn’t have a job, didn’t work for a university, didn’t work for a museum, got little gigs here and there. But all he had was his word. And so, he took that very seriously and it was hard to get him to compromise on much of anything. Until something like World War II kind of makes you do that. But as a result, I think all that stuff is very important to Cavalier Perspective, insofar as [it’s] Breton after World War II. Even though there’s a huge continuity in his interests and what he investigates, he’s a different guy.

48HILLS Is there anything else that you were hoping to talk about, or anything that we left out of this conversation?

GARRETT CAPLES The only other thing I want to mention real quick… right when Breton’s getting ready to go back to France, it’s like 1945, he gives a series of lectures [in Port-au-Prince, Haiti], and there are all these students—poets—who are under a dictatorship. Breton gives his first lecture, and the students really go nuts about it, because he’s talking about how the culture of the people of Haiti is like, the real culture, superior culture, to the sort of imported French culture. These students had a newspaper that they printed his first lecture in. And [Haitian President] Lescot immediately suppresses it. He throws the students in jail for this. But that kicked off a student strike. In two days, it was a general strike. And after about four days, the military stepped in and deposed the government.

And it was not something he intended to do at all, right? You’re not allowed to interfere in foreign affairs as a private citizen of any country. You know, he didn’t cause the revolution, but the immediate provocation that led to it was over the suppression of the issue that had published his speech. He’s not even trying to do something and he sort of accidentally sparks a revolution among those students. And it’s late in the book, and so right before I wrap up the essay, I draw an underline under that. Because I just feel like it’s the poet’s dream, all the revolutionary poets. The dream is, that you just say some shit in that way, and that inspires people to take action. And he actually did this.

CAVALIER PERSPECTIVE LAUNCH PARTY Thu/11. City Lights Bookstore, SF. More info here.