Even locals would be forgiven from thinking they were from the steamy swamps of the South given their sound and subject matter, but Creedence Clearwater Revival is one of the great Bay Area rock bands, hailing from humble El Cerrito and going on to become one of the biggest-selling bands of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s.

Decades of ubiquity on radio and on movie soundtracks (often as helicopters fly over the jungles of Vietnam and Cambodia) bely the strangeness of this rootsy, raggedy, hard-working, and decidedly un-psychedelic band becoming one of the most ubiquitous acts in the world during the hippie era.

None of their albums was bigger—or, for many fans’ money, better—than Cosmo’s Factory, released in July 1970 and the subject of a 50th anniversary remaster from Craft Records out August 14. There’s a new video for closer “Long as I Can See the Light” depicting sons with their dads, many of whom no doubt introduced their progeny to CCR’s choogle.

What’s conspicuously absent is B-sides, rarities, live cuts, outtakes, radio interviews, or the other ephemera so often bundled with anniversary releases. According to drummer Doug “Cosmo” Clifford, that’s because there weren’t any.

“A lot of times when people record, they’ll take 15 songs into the studio and take the best 10,” says Clifford. “We didn’t do that. We had albums ready to go in the order they would be in when they came out in stores. We didn’t record anything that wasn’t going to be on that particular album.”

Blame this on the perfectionism of John Fogerty, the band’s hoarse-voiced, moptopped maestro, whose control over the band is the stuff of legend. Rumors abound that Fogerty would sneak into the studio at night and overdub other band members’ instruments, and though these aren’t true, his idiosyncrasies nonetheless had a major impact on how the band operated—not least his fateful conviction that if the band disappeared from public view for even an instant, their music would be gone forever.

“We made put out three albums in ’69, and John’s thinking on it was ‘if we’re ever off the charts, we’ll be forgotten,’” says Clifford. “Our peers were off the charts a lot of times in between records and tours, and they were not forgotten. But that was how he saw it.”

Creedence’s prolificacy was astonishing even by the standards of the ‘60s rock era, during which bands often released albums every year or several times a year. From May 1968 to December 1970, CCR released six albums, with a seventh called Mardi Gras coming in 1972 when the band was on the outs.

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

But prior to this burst of activity, the band spent many long years gigging around the Bay Area under various names. The first incarnation in 1958 was an instrumental trio of John Fogerty, Stu Cook and Clifford. This band, called the Blue Velvets, took inspiration from the blues and R&B that were seeping into the Bay Area in the ‘50s.

“The Bay Area was a melting pot of cultures and people,” says Clifford. “There was a big shipyard in Richmond, California that was a major player in World War II, and a lot of the workforce came from the South. And when they came out they brought their music—R&B, country, rural and urban blues. It was what we listened to, that and Top 40 radio.”

John Fogerty’s brother Tom Tom joined in 1964, first as lead singer and then as a guitarist, and the band signed with jazz label Fantasy Records, whose co-owner Max Weiss changed the band’s name to the Golliwogs—a racist name, based on an archaic blackface ragdoll, that the band despised.

In 1968, CCR settled on their final name and began playing gigs at bars like Dino and Carlo’s, the North Beach bar where they first played many of the old blues and R&B covers that dotted their albums.

“It was a bar, and not a very big one,” says Clifford, who’d be playing Woodstock less than two years later. “It had a little dinky stage. I don’t know how we even got in there.”

By this time, the Bay Area was the center of the rock ’n’ roll universe. Many Bay bands at the time emerged from the bohemian intellectualism of the city’s coffeehouse scene and were preoccupied with expanding their music—and their minds—outward. Creedence, meanwhile, agreed on a no-drugs, no-alcohol policy during practices and recording sessions, though coffee and cigarettes were consumed prodigiously. (Clifford, though, says the band did indulge when off-duty: “We saved the party for later.”)

The name Cosmo’s Factory comes from the band’s first rehearsal space: a cramped garden shed (“maybe 12 feet by six feet”) in the back of the property Clifford was renting at the time in Berkeley.

“Everybody in the band smoked cigarettes except for me,” says Clifford. “I [was] working up a sweat and I could hardly breathe. Finally. I just threw my drumsticks on the ground and said, ‘you guys are killing me with your cigarettes.’ And Tom came out, and he said, ‘yeah, well, it’s better than working in a factory somewhere.’”

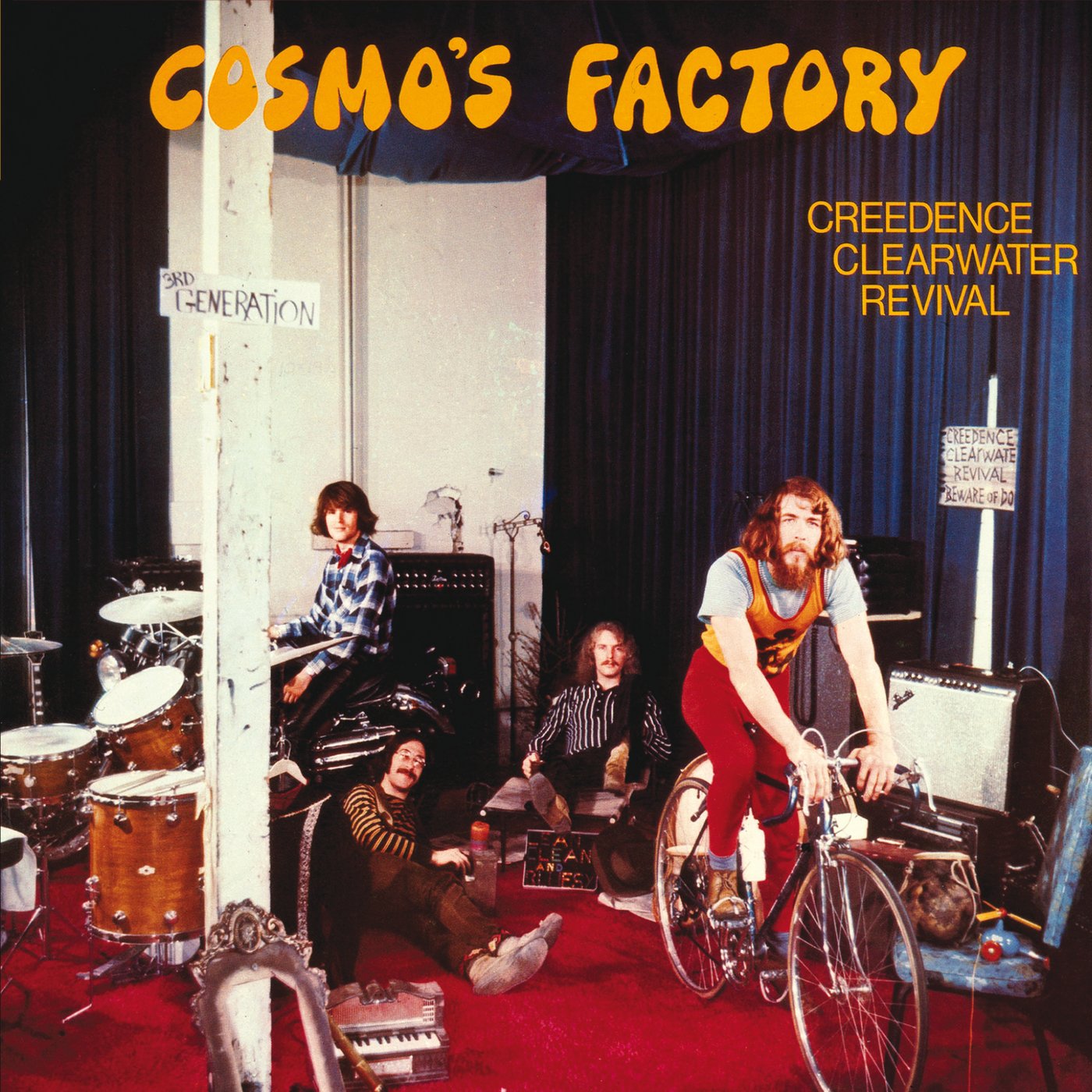

Ironically, the band’s next rehearsal space would be a disused factory. That’s the space depicted on the cover of the album, with Clifford mounted atop the bike he would ride every day to and from practice.

“Going home was all uphill after playing drums for three, four hours,” Clifford remembers. “I was a lean, mean fighting machine.”

Cosmo’s Factory was their first album of 1970, at which point they were absolutely massive; Green River had gone to #1, its follow-up Willy and the Poor Boys to #2. Clifford suspects Fogerty put the drummer’s name on the album to deflect press questions; he was and is press-shy and has not responded to requests for comment on this piece.

The two band members don’t remember much of the specifics of recording. In many ways, Cosmo’s Factory was like their other albums: a bunch of originals, a few covers, bashed out quickly to keep the band on the charts. But it gave them their second #1 album and remains their biggest seller. Its biggest songs are ubiquitous, yet they still have the power to beguile: the folk-art imagery of “Lookin’ Out My Back Door,” the burnt-out sweep of “Who’ll Stop the Rain,” the tension of “Up Around the Bend,” the Satanic conflict of “Run Through the Jungle.

Then there are its two extended compositions, taking up nearly half the album’s runtime by themselves: “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” and “Ramble Tamble.” Both are often called “jams,” but while that’s certainly the case with their 11-minute cover of Marvin Gaye’s creeping infidelity ballad, “Ramble Tamble”—which transitions from rockabilly to a slowly expanding three-chord jam and back again—was rehearsed to the smallest detail.

Cosmo’s Factory was the last album the band made before intra-band tensions began to erupt. Though Clifford and Cook were content to back up a singer and songwriter they knew was immensely talented, Tom began to desire more creative control, and the conflicts between the two brothers led to Tom’s departure after the band’s penultimate album Pendulum.

“He tried to leave the band several times, and Doug and I talked him out of it,” says Cook. “It was more than a sibling rivalry. They weren’t in competition with each other. John just wanted all the control and Tom said ‘I’m going to go do my own thing. It’s reached the point where I didn’t want to work with my brother anymore.’”

John Fogerty pursued a successful solo career and has been engaged in ugly legal entanglements with his bandmates for decades, annihilating any chance of the band getting back together save for a 1980 jam at Tom’s wedding and an appearance at a school reunion in 1983. Tom recorded several solo albums, on many of which Cook and Clifford performed, and died from AIDS in 1990.

Clifford and Cook have continued to tour as Creedence Clearwater Revisited, performing CCR songs with various guests until hanging up the cape in 2019. Cook lives on Roatán Island in Honduras and has not produced much music in the last few decades, while Clifford lives near Lake Tahoe and is currently sifting through a vast archive of solo material. He released Magic Window, an album recorded in 1985, this year.

Neither is involved with the reissue, though according to Clifford: “If we have any suggestions or have any ideas, at least we have an audience at the label. We never had that before.”

I asked Cook and Clifford if they still listened to CCR. Cook says he doesn’t.

“I never liked the sound of the records to tell you the truth,” says Cook. “The record that sounds the best to me is Bayou Country, and then afterwards, they all started getting thinner and thinner-sounding. And I’ve just never been interested, you know, having lived it.”

Clifford is a little more sentimental:

“I hear us when I’m in the produce department of the grocery store a lot. I hear it, I hear it a lot, and every time I hear it, I go, wow, here we are. I’m 75 years old, and I’d had this wonderful career, and there it is—the dream is still alive.”