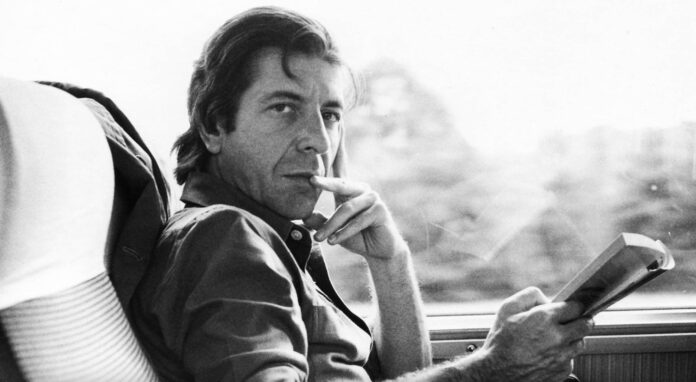

Leonard Cohen is dead, and we love our dead rock stars. Without the inconvenient fact of their living, breathing existence getting in the way of their apotheosis, we can carry the best bits into myth and discard the rest. John Lennon’s place in the pantheon, for instance, is secure as the benevolent, half-smiling face who wrote “Imagine”—never mind that his best work came when he was excoriating himself for being the asshole he, by most accounts, was. Likewise, there’s a risk of memorializing Cohen as the sage who wrote “there is a crack in everything/that’s how the light gets in,” reducing his legacy to his most inspiring quotes and most widely licensed songs at the expense of the complexity that made his work so interesting in the first place. “Hallelujah” is already one of the most misinterpreted songs of all time, and without the man himself as an anchor, it’s easy to let the meaning of his music drift away.

This was not a problem at the Contemporary Jewish Museum’s “Experience Leonard Cohen” exhibit (through February 13, 2022). During his introductory speech, Robert Kory, who became Cohen’s manager in 2004 and the trustee of his estate when he died in 2016, made clear the late Canadian singer-songwriter’s distaste for hagiography. The exhibit features four artists—Candice Breitz, Judy Chicago, George Fok, and Marshall Trammell—interpreting Cohen’s life, work, and career. By seeing him through the eyes of other artists, we’re able to see him not as a remote god beaming benevolently at us from the other side of the firmament, but as a flesh-and-blood human who put out a body of songs, books, and poems that affected thousands.

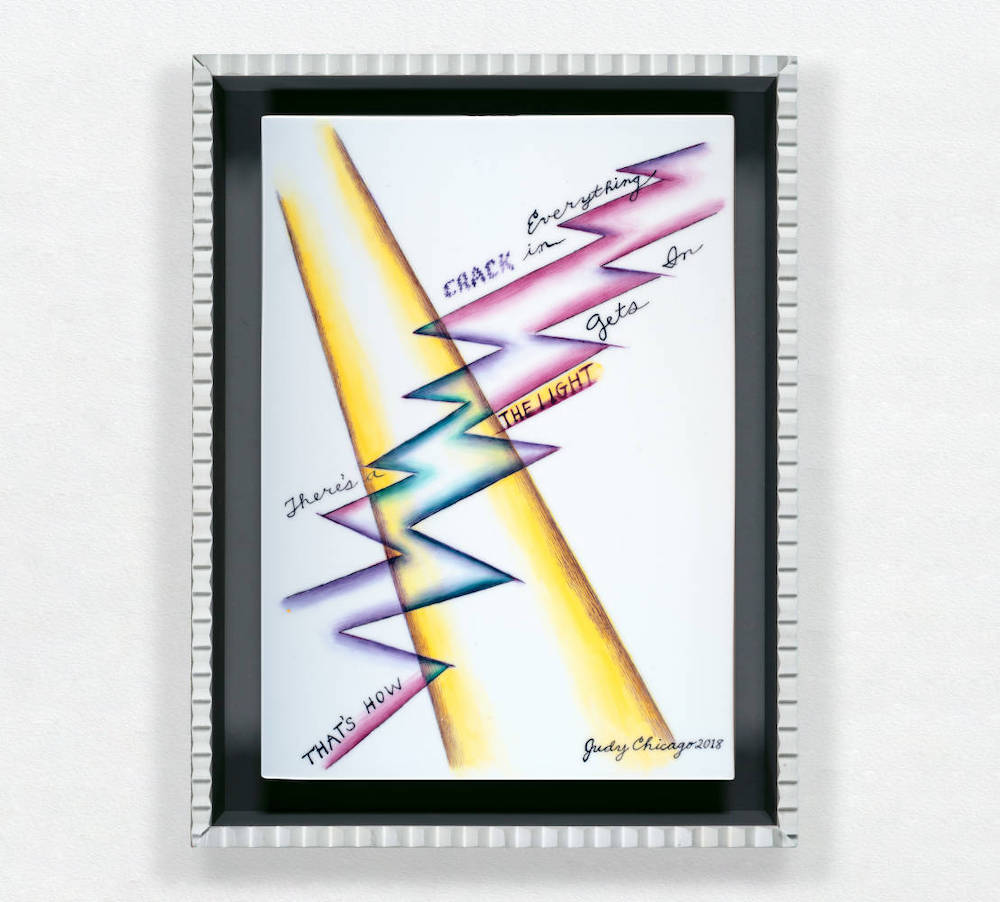

The most sincere outpouring of love was the least artistically challenging of the four exhibitions: Chicago’s Cohanim, a series of 13 porcelains illustrating Cohen’s lyrics. Jews named “Cohen” are said to descend from the ancient Levitical priests of that name, and Chicago—born Judith Cohen—is descended from 23 generations of rabbis just as Cohen’s grandfather was a Talmudic scholar. (Cohanim means “Cohens.”) Most of Chicago’s paintings are literal interpretations of Cohen’s images, and we don’t learn much about the songs we didn’t already know from looking at her porcelains. What mattered was that Cohen’s work had profoundly touched Chicago and stirred something in her own art. Chicago can be abstract, challenging, and confrontational, but Cohanim is simply and touchingly a work of fandom. (Chicago’s current retrospective at the De Young runs through January 9, 2022.)

Breitz’s I’m Your Man comprised a series of videos of older, male singers rehearsing Cohen songs: in one room a choir, in another a row of individual screens displaying life-sized images of another group of singers as their voices gelled into a digital a cappella ensemble. Breitz described it as a tribute to the vulnerable masculinity Cohen embodied, and to older men in general; Cohen was a late bloomer as a musician and made much of his best work in his 50s and onward. One of the singers wore a Breaking Bad T-shirt, another a Canadian flag with the maple leaf replaced by a Batman logo. This was touching. Our creative and intellectual lives are the sum of the media we consume, and that’s as true of an episode of Breaking Bad as it is of a Cohen song.

For Trammell’s site-specific Indexical Moment/um: For Friends, recitations of Cohen lyrics were read aloud and recorded, then played in the CJM’s Yud gallery (that’s the black box that looks from outside like it crashed into the building) and then recorded again. The process is repeated ad nauseam until the words vanish and all we’re hearing is the resonance of the room itself. It’s a direct lift of I Am Sitting In A Room by Alvin Lucier, but while Lucier’s words eventually dissolved into something euphonious, what Trammell came up with sounded more like a dial-up modem connection. He encouraged us to come back later to see how the piece progressed. Maybe it’ll be easier on the ears later on. There was also an Underground Railroad theme that I wasn’t entirely sure fit into the rest of the project. Indexical Moment/um felt a little like something Trammell already had in his head and decided to tweak to fit the Cohen theme.

The most popular exhibit on the day I attended was Passing Through, George Fok’s documentary-installation-DJ mix, assembled from decades of Cohen performances overlapped and juxtaposed on three wall-sized screens. No narration, no interview footage, no talking heads: just Cohen, his older and fedora-crowned self duetting with the suave pessimist who made I’m Your Man and again with the boho womanizer who enraptured the folk scene in the ‘60s and ‘70s. This was the only of the four exhibits that incorporated actual images of Cohen, and its inclusion is a curatorial masterstroke. If the other exhibits show what Cohen means, here’s who he was, not in Fok’s words but in Cohen’s own. From looking at Chicago’s paintings or Breitz’s video screens or Trammell’s pamphlets of Cohen lyrics, you might not guess how funny, modest, self-effacing, and cynical he could be.

I am a casual Leonard Cohen fan. I’ve heard four of his albums, not counting The Essential Leonard Cohen, which got a modest amount of rotation on my iPod back in high school. I enjoyed all of them. I like the candlelit and somber atmosphere of his music, I admire his embrace of synthesizers, and I’m a sucker for any singer with a limited voice and a pitch-perfect awareness of how to work within those limits. But he’s never profoundly moved me in the spiritual way many of the speakers, attendees, and artists at the CJM described. I don’t think he’s overrated. I just have yet to cross the bridge that divides admiration from love.

“Experience Leonard Cohen” inspired me to try. And yet I didn’t come out of the museum knowing anything about Cohen I didn’t already. Maybe that’s the point. Here was an artist, he lived, he died, he made art people loved. If “Experience Leonard Cohen” made anything clear, it’s that the old man would want to be eulogized for nothing more or less.

“EXPERIENCE LEONARD COHEN” runs though February 13, 2022 at the Contemporary Jewish Museum. More info here. Related events include “Five Things I’ve Learned,” a series of online discussions with Cohen biographer Sylvie Simmons starting October 7, and Leonard, My Muse, an online writing workshop Fri/24 through December 17.