One of the greatest independently produced US films before the 1960s (when such things gradually started becoming more common) was ostensibly made only to self-train its neophyte director in moviemaking. Lionel Rogosin was a son of well-off NYC Jewish textile manufacturers who, like many of his peers, felt the need to make work addressing social inequities rather than just “enjoy life” after the horrific revelations of the Holocaust. He decided he’d make a movie about South African apartheid. But realizing that would be an ambitious endeavor, he opted to gain experience by doing something “small” and closer to home first.

That turned out to be 1956’s On the Bowery, an extraordinary look at the onetime flourishing heart of Manhattan which progress and poverty had slowly turned into Skid Row. Shooting on location (Oscar-nominated cinematographer Richard Bagley was well-acquainted with the area—he’d die of cirrhosis five years later), Rogosin used nonprofessionals found there as “actors,” blurring the line between fiction and nonfiction, many passages’ straight if poetical reportage capturing ruined men probably barely aware they were being filmed. There was a thin plot involving an unlucky, unemployed railway worker played by handsome discovery Ray Salyer… who in real life dutifully promoted the finished film, then fended off Hollywood offers and completely vanished. His onscreen figure falls in with “Bowery bums,” gets robbed, sobers up, but stumbles again.

Inner-city hardship and addiction would soon become familiar US reality. But when On the Bowery premiered at the Venice Festival, it won both acclaim and scorn—the latter from powerful American visitors (including Clare Booth Luce) appalled that such shocking images tainted the Eisenhower Era’s front of wholesome, universal prosperity. While it did get an Oscar nomination, the film was just spottily distributed at home. It did, however, fulfill its critics’ worst fears by being far more widely seen abroad, including in Eastern Bloc nations eager to expose chinks in the armor of the “American Dream.”

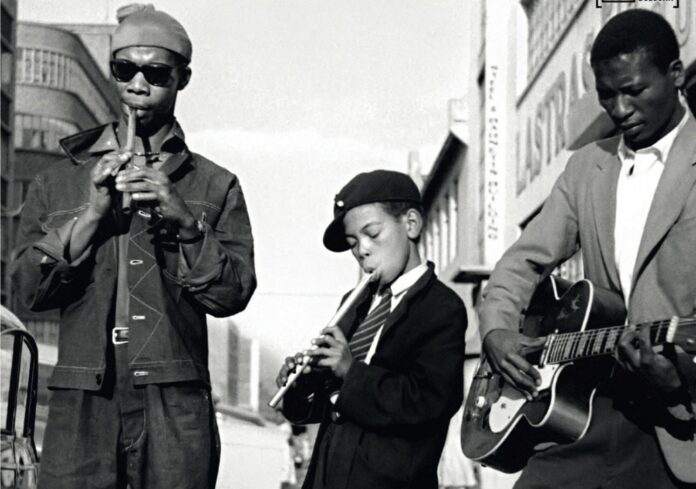

That qualified success allowed Rogosin to make his apartheid film, Come Back, Africa (1959), which was shot in great secrecy to avoid government crackdown. He told officials he was filming various upbeat phantom projects while in fact creating another semi-documentary expose—one capturing everyday racism and grim living conditions, including in a massive Johannesburg shantytown torn down for a whites-only subdivision soon after. Once again, he deployed a nonprofessional-actor protagonist (Zacharia Mgabi) to move the viewer through various situations underlining institutionalized injustice, as our protagonist gets bounced from one low-level job to another for reasons entirely to do with skin color.

If Bowery was frowned upon by some, Africa was simply frozen out—almost no one was ready for a serious celluloid treatment of apartheid at that time, in the US let alone SA. Rogosin went so far as to open NYC’s Bleeker Street Cinemas in order to provide a venue for it and other challenging new film works, just one of several key gifts he gave US experimental and independent filmmaking at a formative juncture.

The prescience that had him tackling the moral morass of South Africa’s system at least two decades before most of the West cared to notice was also on display in his next feature Good Times, Wonderful Times, perhaps the earliest to take a vehemently anti-Vietnam War stand. Utilizing footage from national archives around the world depicting war propaganda and grisly casualties, it cuts between those horrors (including Auschwitz, Stalingrad, Hiroshima et al.) and a London cocktail party where toffs striking various quirky and jaded postures toss off bon mots like “War is one way of keeping the population down” and “It’s all fraught with danger, women who don’t shave their underarms!” The compare-and-contrast indictment of our “civilized” hypocrisies looks crude now. But in 1965 it was doubtless jolting—and its blunt anti-war statement surely raised a lot of consciousnesses when distributed to an estimated one million draft-age students on US campuses.

A more conventional documentary—in that it contains no apparent staged or scripted material—was Rogosin’s 1973 Woodcutters of the Deep South. It examines an exploitative holdover from sharecropper and Jim Crow days, in which men razing trees for the Alabama pulpwood (i.e. paper-manufacturing) industry were kept in virtual indentured servitude, manipulated into “company store” debts while allowed no access to a union, unemployment benefits, health care, or base hourly wages. As with any lowest-rung, “unskilled” job, these were mostly the lot of Blacks, as well as “poor whites”—people who could barely survive on a maximum yield of $2500/year, but also had no better options. While the film bogs down somewhat in the Woodcutters Cooperative trade association’s internal politics, it remains a valuable historical record.

Rogosin’s thorny choice of subjects made his projects’ financing ever more difficult to come by, so he finally gave up filmmaking altogether well before his demise in 2000, at age 76. But in recent years much of his work has been restored, with six films (also including 1970’s Black Roots, with African-American musicians discussing segregation, and 1973’s self-explanatory Arab Israeli Dialogue) currently streaming on the NYC Metrograph Theater’s “At Home” site, along with making-ofs created by his surviving son Michael Rogosin. For further info on and access to the whole Lionel Rogosin x 6 series, which is available through May 5, go here.

New streaming releases of note:

The White Fortress

It has been just over a quarter century since Sarajevo was subject to the longest siege of a capital city in modern warfare’s history, an onslaught of nearly four years. But while the town now looks tranquil enough, even (from some perspectives) picturesque, life there still appears hobbled in the wake of war. At least it is for Faruk (Pavle Cemerikic), the kind of youth who looks at once babyfaced and ancient with weariness. His mother is dead, his father unknown; he lives with a grandmother too depressed to get off the couch. His prospects appear no better than metal-scrapping with a brusque uncle, and accepting the odd dubious job from a slightly older pal whose subserviance to a crime boss has him involved in sex trafficking and worse.

Then by chance Faruk meets Mona (Sumeja Dardagan), who has everything he doesn’t: An ongoing education, an intact family, wealth, options. But she also feels suffocated, as her politically ambitious parents want to shuttle her off to relatives in Toronto while their marriage of convenience disintegrates, or whatever it’s going to do. Thus she and Faruk recognize each other as kindred souls.

The White Fortress, which was Bosnia and Herzegovina’s feature submission to the Oscars this year (it didn’t make the final cut), seems in outline like another Romeo and Juliet update, while to an extent the narrative also leads us to expect a grim crime thriller. But Canada-based writer-director Igor Drljaca’s film transcends those things, or at least proves disinterested in them. It is more tonally unpredictable and stylistically adventuresome than one first anticipates, with a spectral, quiet, interior feel. Those qualities end up making the whole less a statement of straightforward storytelling than poetical essay-slash-metaphor. I’m not sure it all works completely. But I am sure it’s going to be sticking in my mind for quite a while—certainly long enough to land on a list of this year’s best movies. Game Theory has released it for streaming to US digital platforms.

Sexual Drive

Not bloody likely to wind up on any Academy Award shortlist is this enjoyable Japanese exercise in comedic bad taste, served up in three interlocking stories. First up, a man whose wife has just left for work at the hospital is paid a home visit by a very odd man who claims an affiliation with said wife—one that he explains in great detail, including the phrases “writhing in ecstasy” and “love juices.” This is kinda gross, then pretty funny, then really gross again, though the entirety of Sexual Drive offers no content (language aside) more graphic than shots of people masticating in closeup.

Next, a woman driving by herself for the first seems to accidentally hit a weird guy (spoiler alert: we’ve seen this guy before) who turns out to want something entirely other than a ride to the hospital, and to want it specifically from her. Finally, another attractive youngish woman exits a bar where she was drinking solo to enter a grungy ramen joint, where her actions thrill and disturb a man sitting at the end of the counter.

Clever enough to make us forget the claustrophobic limits of its budget-minded narratives (each of which could conceivably be performed on a stage), this film by writer-director plays on particular Japanese ideas about sex, food, humiliation, and propriety in ways that are deliberately discomfiting. But they’re also somewhat bracing in their go-for-broke-ness, as are the very game performers. This peculiar exercise in the humor of mortification may make you squirm, but it will almost certainly also make you laugh. Film Movement has released it to US Digital and On Demand platforms.