My hour with artist Pippa Dyrlaga, discussing her latest exhibition Biophilia, took place between two worlds. To begin, Heron Arts itself, where the work will be exhibited until July 21, is a multiversal gallery of sorts. The Boston ivy encircling the entrance and the avian name suggest a portal to an enchanting macrocosm parallel to our own.

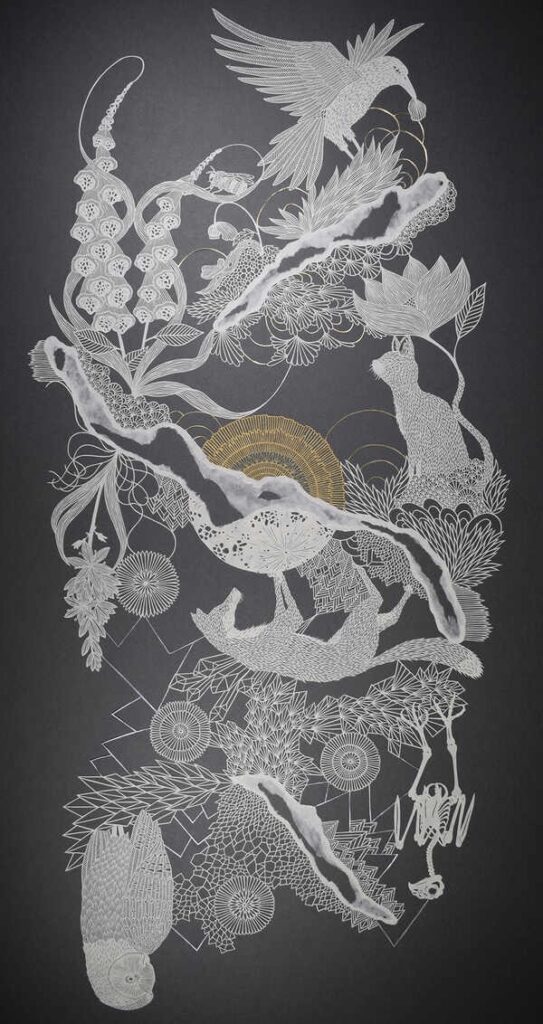

Similarly, Dyrlaga’s work itself is bridge-like. The 27 intricate cut-paper pieces on display are a summoning of nature amid urbanity. Just like the psychopomps she carved into paper, named for the ancient spirits that guide souls to the afterlife, the artist helps her visitors straddle two worlds—the urban one they inhabit, and her own.

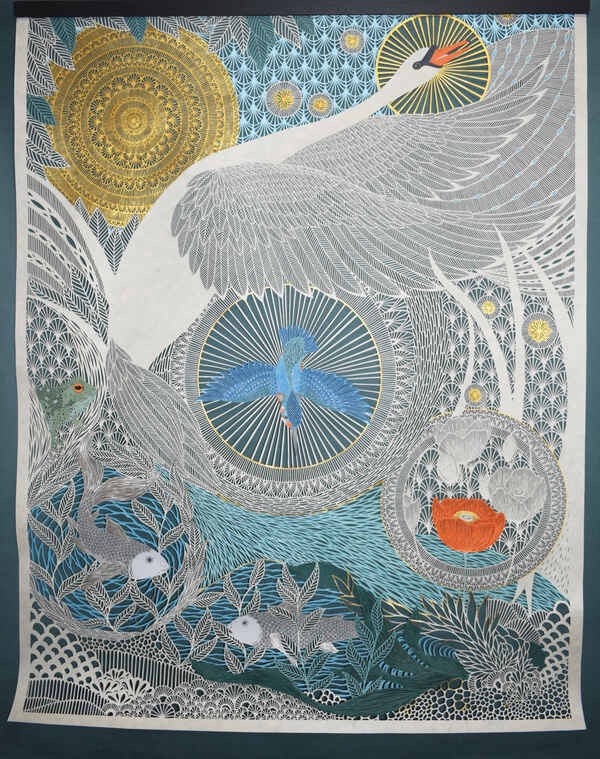

Dyrlaga grew up on a canal boat, immersed in nature. She shares with me her family’s inside joke about the kingfisher: Its swiftness and tendency to escape the moment her mother pointed it out turned it into a natural myth, even an expression, among the Dyrlagas. The same way nature became a familial lexicon growing up, today, it not only forms the theme around which Dyrlaga’s work orbits, but also provides the vocabulary that animates it.

The highest praise for “Biophilia” might be that Heron Arts now feels like Yorkshire, where Dyrlaga currently resides. It seems as if the concrete has been infused by the roughness and vulnerability of nature. This accomplishment is all the more impressive considering that medium through which it’s achieved is paper. Dyrlaga appeared to subtly relish people’s anticipatory tension around her hanging paper pieces. “Summer,” for instance, hangs suspended from two strings, in between two doors. During my walk, rogue gusts of wind would shyly attempt to fold the piece. Imagine Klimt’s “The Kiss” hanging frameless, at the mercy of the elements, and picture the gallerist’s reaction.

But this is precisely what’s at stake here. This is exactly what’s meant by nature as vocabulary. The fact that Dyrlaga borrows nature’s vulnerability and ephemerality as a language means her pieces are not only about nature: They are nature. This is why paper is the only possible canvas for her work. Paper itself is a multiversal medium. Before artists like Dyrlaga began carving it, paper was the vessel of words, the conduit through which our minds speak into the future, another bridge.

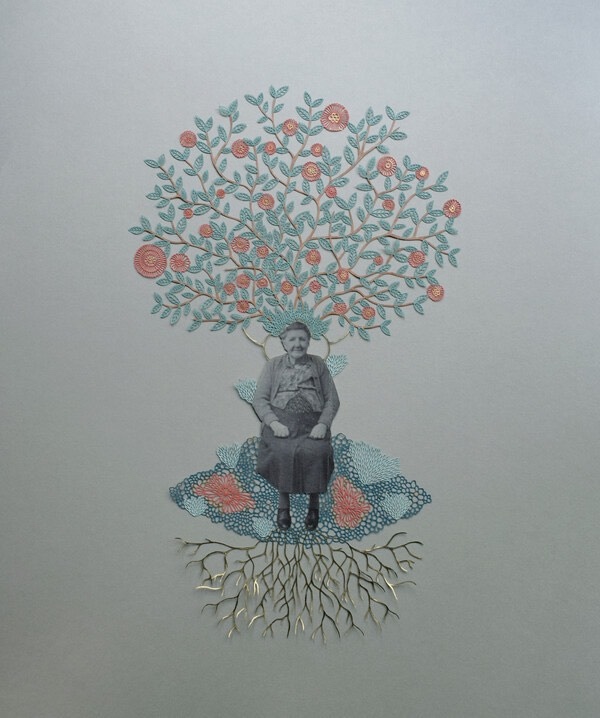

Nature as the original ferryman—the Charon that starts and ends it all, guides us, subtly, into the underworld. Dyrlaga obsesses over this. “Gaia,” “Memory Fruit,” and “Terra Mater” are black-and-white pictures of long-gone matriarchs transforming into trees. They are poignant, powerful reminders that what we call death is nature: rough, vulnerable, worthy of reverence. The way Dyrlaga pictures these women as goddesses starkly contrasts with how culture associates feminine divinity with youthful, fiery power, the Wonder Woman. These women were homemakers, as she puts it, creating hearth the way trees bear fruit.

“Memory Fruit” is a meditation on how their legacy is edible—sometimes literally—and hence an integral part of us. “Terra Mater” surrounds the elder with everyday plants (bushes, dandelions, nettles, daisies, raspberries). It’s Dyrlaga’s way of asserting that the nonphenomenal is the most precious miracle to witness. (The grandeur of the unassuming reverberates through the Biophilia space.) “Moss,” another hanging piece, attempts to replicate the complex moss patterns we often overlook on our hikes.

The organic nature of Dyrlaga’s practice ensures that the pieces slowly “grow” in her studio. Her pieces often don’t look the way she intended them to when she started creating them. Because her journey is one of revealing absences amidst presences, because cut-paper is the art of negative space par excellence, Dyrlaga is acutely aware of the things that fail to seize our fleeting attention. Her work is an important testament to the distinctiveness and majesty of the overlooked, an invitation to reconsider the worlds we tread upon.

PIPPA DYRLAGA: BIOPHILIA runs though July 23 at Heron Arts, SF. More info here.