Among a hundred canvases, mine were always recognizable. —Tamara de Lempicka

The Polish-American painter Tamara de Lempicka (1894-1980), whose first major US retrospective runs through February 9 at the de Young, has been known to art aficionados for a century. But her distinct, eclectic style, which blends Flemish Old Master realism with Cubist stylization, proved problematic during her lifetime: She was a Jewish woman and an aristocrat (by birth and by marriage), who could indisputably paint like an angel, but went against the grain of current practice and general social mores.

Lempicka studied in Paris after the Great War under Cubist André Lhote, whose decorative version of Cubism was disparaged as timid by la bande Picasso (i.e., most of the art world of the 20th century). Lempicka in turn shunned that Spanish artist’s “novelty of destruction,” or creative destruction, seeking instead to imbue her portraits with elegance and sex appeal—sometimes to an exaggerated and even comical effect, but always vividly and memorably.

Both painters were recyclers avant la lettre. Picasso stole from everyone, by his own admission, during his whole long life. Lempicka borrowed motifs from Ingres, Michelangelo, Botticelli, Bernini, and various Mannerists throughout her shorter career, in order to populate her graceful, sexually charged depictions of roundelays in Paris’s smart set—both aristocratic and bohemian—in the two decades of relative peace, prosperity and liberalism between the wars.

Born in Warsaw and later living in St. Petersburg, Lempicka was raised in wealth and luxury. During the Russian Revolution she was forced to emigrate to Paris, like others of the elite classes. Her lawyer husband, saved from execution by Lempicka’s seduction of a consular official, proved unequal to making a new life in France, so Lempicka, an avid museum-goer since a 1911 trip to Europe, decided that art might return her to respectability and glamor. She proved to be an able self-promoter as well as a dazzling portraitist.

She had Hollywood-style celebrity photographs taken to depict her, always perfectly coiffed and styled—“the baroness with a brush,” as American newspapers dubbed her after her 1939 emigration here—enjoying her designer-modernist rue Méchain apartment, stage set, and showroom. (In 1948, after the war, she returned for a nostalgic visit, taking in the current art climate, posing for photographs in a veil and flowing gown, with eyes closed, amid curtains and classical statuary, as if auditioning for Cocteau’s Surrealist fairy-tele, La Belle et La Bête.)

Lempicka also rode the wave of the “modern woman” media trend in prosperous, socially liberal and sexually tolerant Jazz Age Paris. The slinky young women inhabiting her portraits and nude studies come from the cosseted upper classes as well as from the erotic demi-monde, parallel worlds which the adventurous artist explored freely—perhaps even touristically, in a way—during her 1925-35 decade of fame and fortune, which coincided with the height of the international Art Deco style that she embraced. As she said, “I live on the sidelines of society, and the rules of the normal society do not matter for those on the sidelines.”

One hundred and twenty works—paintings, drawings, and even some Art Deco gowns and home furnishings— have been assembled by the Lempicka expert Gioia Mori and the de Young’s Furio Rinaldi, with the cooperation of the artists granddaughter and great-granddaughter. Viewers new to Lempicka will find them beautiful and approachable. Several pieces have additional points of interest.

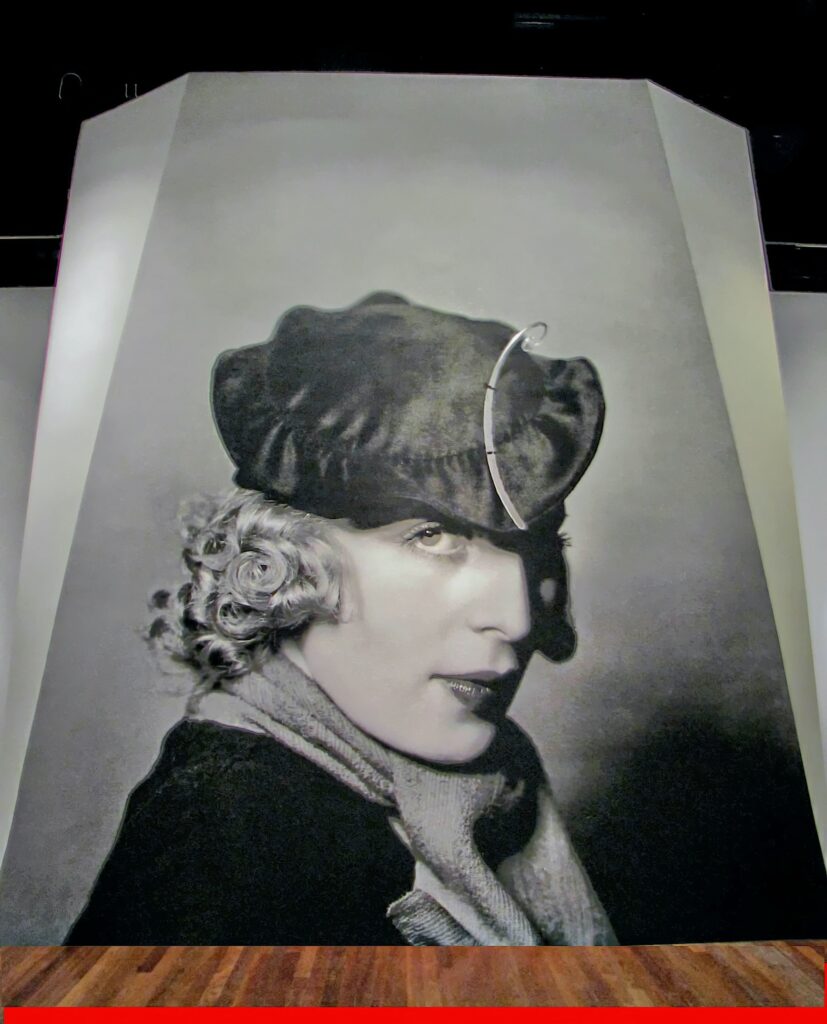

Madame d’Ora’s 1929 enlarged photographic portrait of Lempicka at the show’s entrance shows the artist elegantly dressed and carefully posed (and composed), casting an attentive appraising eye toward the viewer. d’Ora aka Dora Kallmus, was a groundbreaking Austrian fashion photographer who shot other celebrities of the time, including Josephine Baker, Colette, Coco Chanel, and Alban Berg.

De Lempicka’s “Her Sadness (Portrait of Madame P.),” from 1923, depicts the poet Ira Perrot, a Parisian neighbor of Lempicka who became her friend and lover for a decade, before a falling out over another portrait. The writhing branches in the background symbolize the poet’s overwrought thoughts, captured in a poem excerpted on one of the wall labels. In “Portrait of André Gide” (1925), the French writer, eyes squinted almost shut, is tightly framed and thus appears monumental, despite the modest size of the painting. Gide scandalized Paris—even in the liberal 1920s—with his novel about homosexuality, and he championed Lempicka’s gay-friendly images.

“Portrait of His Imperial Highness The Grand Duke Gabriel” (1926) depicts a member of the Romanoff family living in exile in Paris (much like the young artist herself in 1918-19, who for a time lived on selling the family jewels). The grand duke, a former military officer, is shown in uniform, but his haggard features and haunted expression testify to his treatment by, and lucky escape from, the Cheka, Lenin’s secret police.

“La Belle Rafaéla” (1927) is one of several nudes made of a striking-looking young woman—a sex worker—whom the artist observed and approached in the Bois de Boulogne. She became Lempicka’s lover as well. Female nudes by women artists were all but unheard-of until Lempicka painted several, probably inspired by the harem paintings of Ingres, with some of them depicting lesbian embraces.

“Young Woman in Green” (ca. 1931) features the young blonde model who appears in several paintings, perhaps a composite of the artist and her daughter Kizette (who would become her biographer). Note the anatomical liberties taken with the subject’s oddly shaped left arm, recalling those that Ingres took with some of his models, and the polished planes that suggest Cubist counterparts, monochrome and transparent, but here, a generation later, painted green and buffed to a high sheen, as if cut from sheets of metal. Lempicka’s paintings with their shallow space, and both model and background crowded toward the picture plane, suggest bas reliefs.

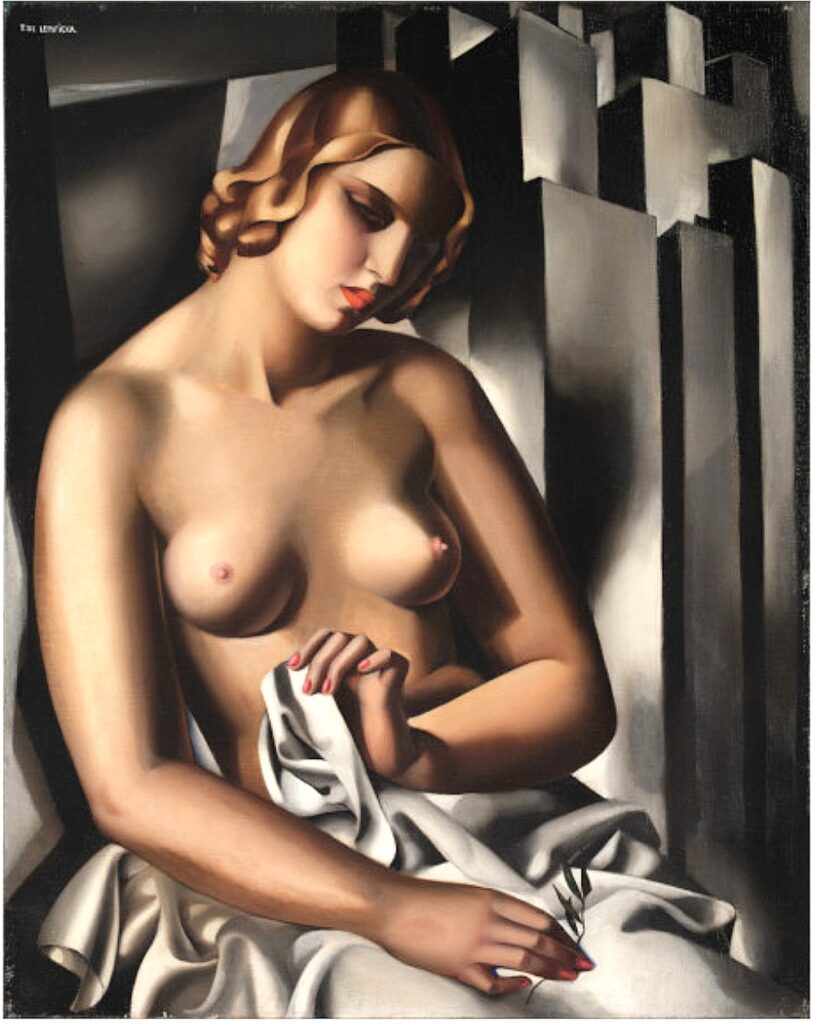

The half-naked young woman in the foreground of “Nude with Buildings” (1930) is juxtaposed with a monolithic cluster of windowless, polished metal skyscrapers. The subject contemplates a sprig of indeterminate greenery held in her right hand, while her left hand adjusts some draperies. With time’s retrospection, it’s hard not to see this vulnerable figure laid bare before an unseeing world as prophetic: A few years after this painting was finished, art-world tastes would change, and Lempicka’s career would falter. By the mid-1930s, she had fallen into depression—a “mystical crisis,” in one writer’s characterization—and seek both pharmaceutical relief and religious and art-historical consolation, adding to her repertoire nuns and saints, reflecting the faces of those who had helped her.

1940’s “Escape (Somewhere in Europe)” (1940) repeats the composition of “Nude with Buildings,” but in a more serious vein. Lempicka had discerned early the menace of Nazism, and she persuaded her second husband, the Austrian Baron Raoul Kuffner (whom she had met win 1928 while painting his mistress, a famous dancer) to sell his holdings and emigrated to the United States. The couple settled for a time in New York and then moved on to Beverly Hills, where a colony of European artistic ex-pats worked in the movie industry. “Escape” was painted in solidarity with the displaced and dispossessed of the war. The buildings in the background are no longer fractured by formalism, as before; their more realistic depiction now echoes the very real threat of fascism.

Tamara de Lempicka’s Art Deco portraits will be her main claim to fame in the future, as now. All of her paintings are carefully composed and exquisitely painted. But the exacting care that makes her work so stunning can work against it, freezing it into a too-specific era—as is the case of the academic painting of the nineteenth century, still sniffed at by cognoscenti. There are times when we want to feel the storm within the paint, to quote the visionary (and technically inept) painter Albert Pinkham Ryder.

Still, no artist can do everything; nor should we ask that of any of them. Lempicka is receiving a well-deserved and belated second look by art tastemakers; perhaps her true audience has been looking, avidly, all along.