“In the world of art where a bit of knowledge can sometimes be stretched a bit too far, I’m glad to say that my experience seems to bring me more rewards than my knowledge,” Stephen Namara told 48hills.

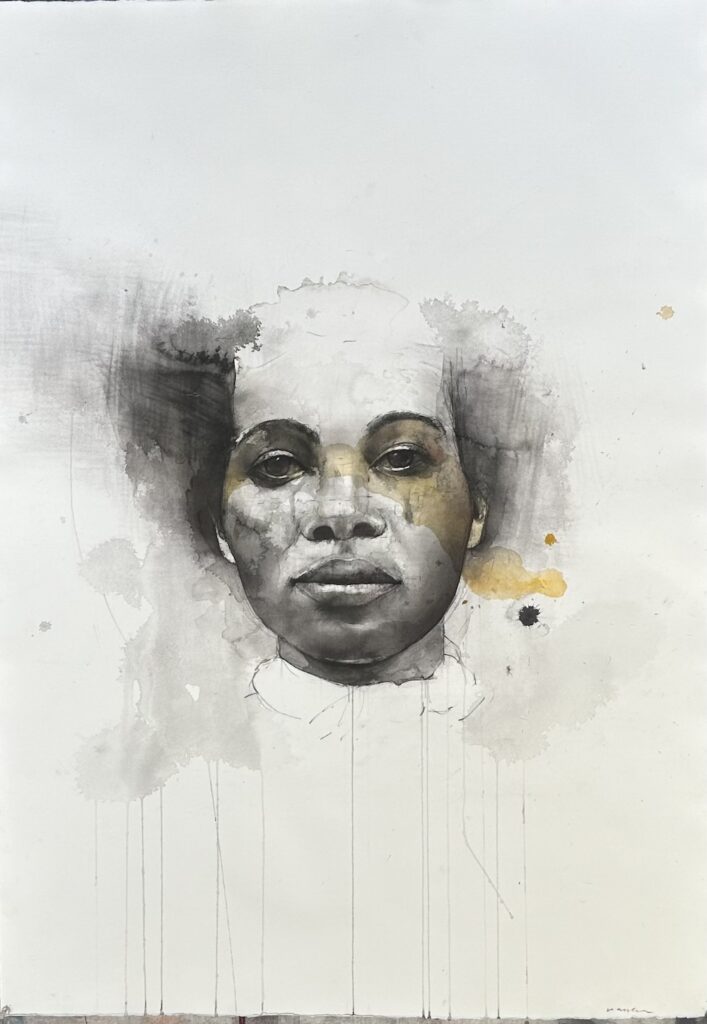

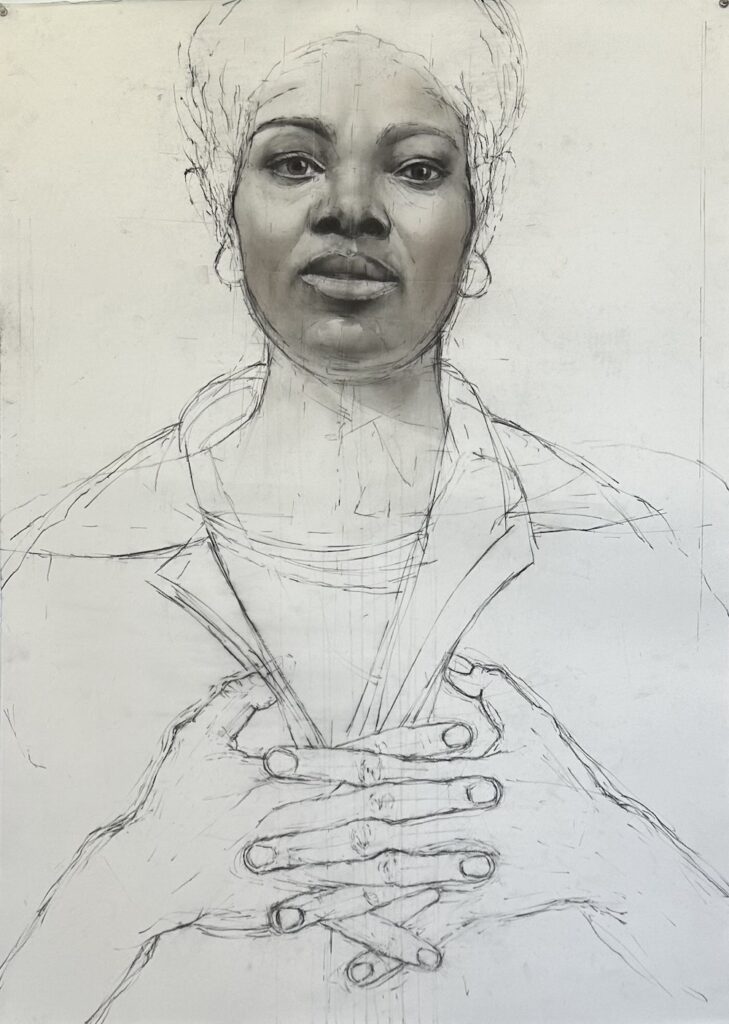

In portraits and abstract works, Namara explores the complicated emotions that arise in our attempt to live a normal life in the face of extraordinary circumstances. In delicately rendering art in lean materials, he reflects our desire to protect ourselves in the battle against anxiety, anger, and grief.

Namara grew up in two very different corners of the world: East Africa (Kenya and Uganda, to be exact) and the midwestern state of Missouri. He came to San Francisco to attend the San Francisco Art Institute in 1979. Since the mid-’80s, he’s kept a studio at Hunter’s Point and currently lives in the Golden Gate Heights neighborhood.

“San Francisco has a spirited creative ecosystem. The things that drive me crazy are the very things that make it worth putting up with, worth living, and working to preserve,” Namara shared.

“I love the generosity of the artists, particularly the distinguished elders. I like knowing people around me. The art world here is still mercifully small. And the city’s vibrant arts scene still attracts a diverse group of creative individuals,” he continued.

Namara stumbled into art school by chance, through two seminal experiences. The first was coming across a drawing by Chicago artist Charles White (1918-1979), whose figurative Social Realist drawings are a clear influence on Namara’s own work.

“White’s depiction of a monumental standing figure exuded such endurance that it appeared eternal. I was utterly captivated. His drawings are not strictly portraits, as they transcend mere pictorial representation and embody profound themes,” he said.

In his third year of college, Namara enrolled in a drawing class at the University of Missouri to fulfill a requirement for an engineering degree. He displayed a natural talent and a professor in the program encouraged him to go further with his art. He had never considered it a potential profession. A detour ensued.

“Taking that art class was the very first time, I felt free. It was like an initiation, I stopped thinking about the future as if it was something I could control or predict. It wasn’t something that existed outside of me. Instead of hoping or fearing what might happen, I dealt with things as they were,” he said.

With only one year left to complete his engineering degree, Namara dropped out of the program and enrolled at SFAI as a junior, eventually taking classes at SF State University as well. He didn’t look back.

“At the time, there were stories of renowned artists like Julian Schnabel, icons of individualism who ultimately achieved success and wealth. Being an artist, steadfast in one’s vision of the world, was seen as a path to praise and success. It was believed that one could be an artist and make a living,” he said.

Though in retrospect, moving to a new city short of cash and family support was a terrible idea.

“I soon realized that it took more than just a sink-or-swim attitude to navigate the deep, swift current of art and life. I can say now that it takes buckets of sweat, years of experience, an innate confidence, and a visionary sense of direction to even get to the brink,” he said.

But it was during that perilous time that he truly found his footing.

“In the early 1980s, [the SFSU] art program was simply incredible. Professors like Robert Bechtle, Richard McLean, and Stephen de Stabler taught classes that inspired me. I attended classes led by Barbara Foster and soon began experimenting with lithography, drawing, and intaglio techniques,” Namara said.

He secured a studio at the Hunters Point Shipyard in spring of 1985. Its community of artists has played a significant role in his artistic development over the years.

Namara calls himself a figurative painter whose work is not always realistic. He believes that art should ultimately express interior life, adding that creation is essential to his personal well-being.

“I think art should strive to connect with people through the emotions conveyed in the texture, the quality of paint, and the images. As a human being, I react to everything around me, and I paint what I see, sense, and feel about the society we inhabit, trying to create an ordinary life in extraordinary times. It’s evident to me that others share similar sentiments, it’s just that few people are expressing it through art,” Namara said.

Regarding the particulars of a definitive look and feel, he says that while many artists are celebrated for their distinctive styles, he sincerely hopes that he never becomes synonymous with one specific aesthetic. Namara consistently strives for something “slightly novel”—even if some attempts may not yield the desired results.

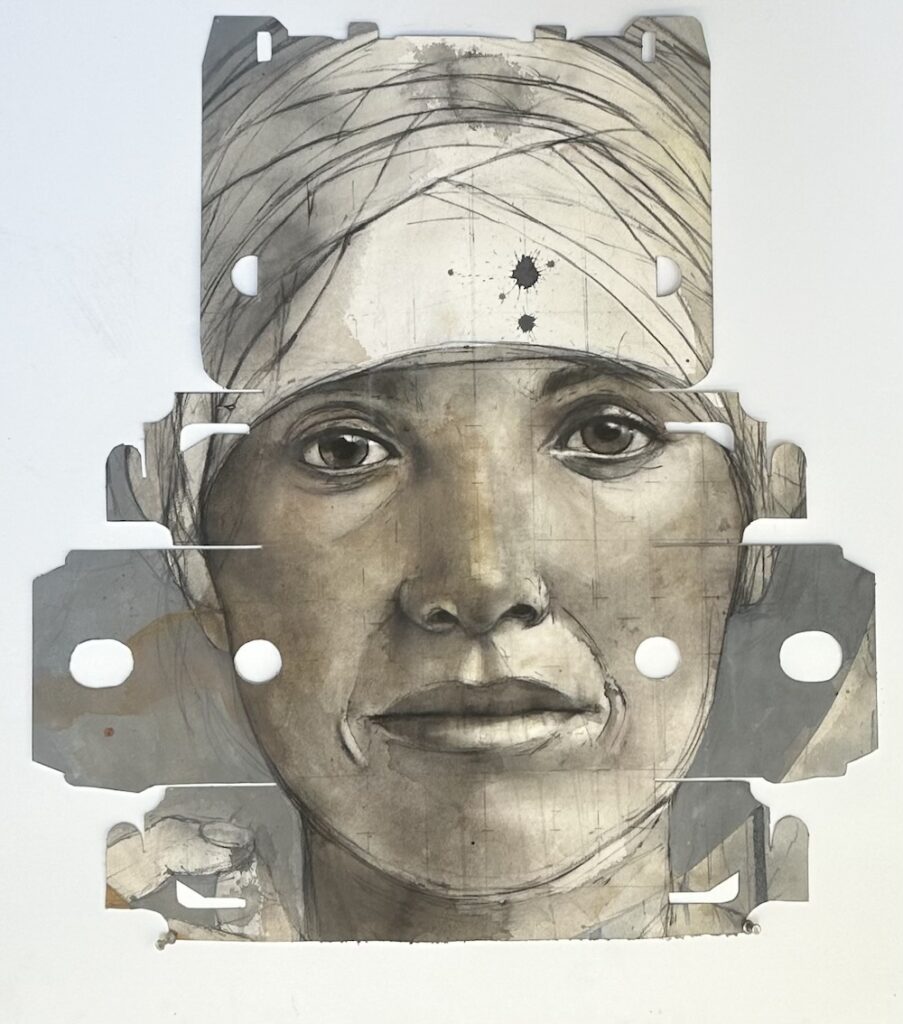

“Maintaining a constant state of evolution is crucial. The use of dry pigments and pencil as my primary medium is fundamental to everything I do. I cherish the immediacy and honesty of it. At its core, minimal preparation is required. I can begin with a pencil or dry pigment and create something entirely from nothing on a sheet of paper, akin to the ultimate form of alchemy. There seems to be almost no limit to the types of marks I can make and with each drawing I undertake, I feel like I’m discovering a new graphic language,” he said.

Despite years of experience, Namara still encounters challenges that present a feeling of being inadequate. An internal dialogue will arise where he wishes that he could do something better, learn to do it better, and even feels reluctant to show his work to anyone.

“The process is filled with insecurities. I think to myself, ‘Did I really do that? That’s pretty clever. I’m not so bad after all.’ But then I’ll think, ‘Not really,’” Namara said.

A typical day in the studio for the artist begins in the morning, with a backdrop of jazz instrumentals (John Coltrane, Red Garland, Bill Evans, etc.). Once he gets going, his work day has no set time limit.

“In this process, I discover certain elements that are beyond my control. Of course, I’ve had dry periods and it’s very difficult, but that goes with the territory,” he said.

Namara says that, for him, the artist’s role in the studio, “alongside the frankly unreasonable investment of labor,” is to sift through the clutter and extract the essence and core of the work.

“It’s partially trial-and-error. I can afford to make mistakes. I do make mistakes, discard them, or revisit them. What I propose is that during the drawing process, numerous ‘accidents’ occur. The pleasure for me lies in recognizing these accidents, embracing them, and moving forward from them. If a drawing initially starts as a dog but transforms into a pig, I allow it to be a pig or something in-between,” he said.

Regarding methods and materials, Namara says there is always a specific feeling he is going for, but the means by which he achieves is a function of the mechanical nature of his tools. A moment of grace becomes a graceful line and texture in Namara’s exquisite works, such as in his 2024 works Phantom (watercolor and ink) and Different But Not Less (conte crayon and dry pigment). He also notes that the technique of creating layers of dry pigments rubbed gently and lightly on top of each other gives his work a palpable sense of fragility.

“I have no doubt that the creative process starts with initial ideas or intuitions that undergo a gestation period. I am not interested in creating work solely based on my existing knowledge; instead, I strive to create work that also explores and delves into the unknown. The work serves as a reflection of my personal exploration and introspection as I grapple with ideas, hunches, and emotions. This process is ongoing, with a constant back-and-forth,” he said.

As for how the world around him and the flex and release of societal changes influence his work, he starts by saying that art is deeply personal. He elaborates by illuminating the importance of art driven by justice and personal conviction yet maintains that it is equally meaningful and worthwhile if not in direct response to political events.

“While this is a particularly terrifying moment in American life, as our president fulfills his draconian promises, current events undoubtedly influence my work. In some cases, the connection is direct and specific, while in others, it’s more subtle. Who can escape? Czech playwright and dissident Václav Havel wrote in Summer Meditations, ‘There is only one thing I will not concede: that it might be meaningless to strive in a good cause.’” Namara said.

Namara’s most recent exhibits include the two-person show “UNSEEN” at the Drawing Room-Annex, and solo show “Between Realities” at Mill Valley’s Throckmorton Theatre. he will be included in the annual summer group exhibition “Undercurrents” at Andra Norris Gallery in Burlingame, his primary representative, opening on June 7.

Going forward, Stephen Namara says he is most pointedly drawing inspiration from Baroque paintings, integrating his engineering-architecture studies and African background, while creating a connection between the image and the viewer. He wants us to see ourselves in the vulnerability and precariousness present in each portrait.

“Something that has stayed with me since the first art class is that one of the main aspects of the human experience is the void, the existential void. Being aware that we drift in an incomprehensible and fragmented world. Alongside this there is fear, uncertainty, and the contingency of life itself. In my work, I try to somehow find ways of representing this experience,” he said.

As we await the next body of work from this accomplished and dedicated artist, he reminds us once again of the importance of art in our complex lives, whether as creators or viewers.

“Art provides us with a unique language to comprehend our existence in this world, a language that nothing else can offer,” Namara said. “Being human is challenging and often contradictory, and artists possess the means to delve deep, bringing things to the forefront to help us all confront them.”

For more information, visit his website at stephennamara.com.