People like me sometimes get eye-rolled for being among the admittedly large number of people overly nostalgic for the movies of the 1970s. But it’s easy to explain why the period appeals: The notion that films were much more commonly made for actual grown-ups then is borne out simply by noting that the big Christmas releases for 1971 were as follows: A Clockwork Orange, Dirty Harry, Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs, Polanski’s Macbeth, and savage satire The Hospital. All but the last were “ultra-violent,” and all controversial in their way. (Yes, there was a Disney musical and a James Bond in there, too, but never mind.) The target audience or audiences were different then; there were a lot less one-size-fits-all films, let alone ones with a median demographic of teenagers. The whole family wasn’t expected to see these films—it would even have appalled the studios if they had.

But one movie released a few months earlier managed to cause more offense and general repulsion than all the above-noted, not just in the U.S., but around the world. That was Ken Russell’s The Devils, a U.K.-U.S. coproduction. It was a costume drama, like the director’s prior Women in Love and The Music Lovers, but with a considerably more incendiary (in both the literal and figurative sense) theme. The source was Aldous Huxley’s 1952 The Devils of Loudun, a novelistic account of real-life events in 17th century France involving politicized accusations of sorcery—the Machiavellian Cardinal Richelieu utilized the hysteria of some all-too-cooperative Ursuline nuns as an excuse to get a rival cleric burnt at the stake.

But the Brave New World author’s tone of droll, disdainful amusement at this grotesque footnote is nothing like Russell’s approach, which is a sort of leering grand guignol. The latter artiste professed himself a “devout Catholic, very secure in my faith,” calling The Devils “my one political film. To me it was about brainwashing, about the state taking over.” But to many viewers it felt like the most deliberately blasphemous thing imaginable, its every image and action an affront to religion—not to mention “taste.”

You can party (or recoil) like it’s 1971 this Fri/12 at the Balboa, where The Devils will be shown in an “Unrated Director’s Cut” by Movies for Maniacs. This is actually meaningful, because Russell’s phantasmagoria was extensively cut by censors in many countries at the time of its release. While the commonly excised footage has been restored since, the full movie remains very patchily available—in any version—on home formats. After all this time, is Warner Brothers still appalled by what its production funding wrought? Quite possibly, since the restored Devils hasn’t been officially released in the U.S. A significant omission, because this 54-year-old historical drama is nearly as popular as it is notorious, and has seen its critical stature gradually ascend over the decades.

Russell’s script, while greatly condensed, does hew rather closely to the known incidents recounted in Huxley’s book. In 1634, Urbain Grandier (played by Oliver Reed) is the fashionable chief priest in the medieval fortress town of Loudun. He’s handsome, charismatic, and ambitious—as well as randy, something not at all unusual amongst Catholic clergy at the time. Still, his behavior was considered shameless in some quarters, especially after he seduced, impregnated, and abandoned the daughter (Georgina Hale) of a prominent citizen (John Woodvine). His titillating reputation reached the ears of unstable prioress Sister Jeanne (Vanessa Redgrave), who became obsessed. When he declined her invitation to become the nunnery’s official confessor, she went off the rails. Her claims of “demonic possession” soon spread to others in the convent (mostly well-born women consigned there simply because their families couldn’t afford marital dowries) in what became a lurid public spectacle, and a tool for Grandier’s enemies to arrest him for alleged witchcraft. As portrayed here, the weak, decadent court of Louis XIII (Graham Armitage) did little to stop this persecutional farce, controlled as it was by Richelieu (Christopher Logue). The gruesome means used to pursue “justice” were hardly different from those of the Spanish Inquisition.

This same chapter also inspired a play by John Whiting, an esteemed 1961 Polish film (Mother Joan of the Angels), a Penderecki opera, and other works in various media. But Russell, while faithful to the chronology of events and Huxley’s critique of power, ruffled more feathers than any other interpreter via the characteristic, caricaturing flamboyance of his vision, which here straddles parody, horror, sexploitation and serious drama. The only narrative element he added was the plague—in all its pustule-covered, rotting-corpse glory.

But nearly everything else, from the royal court’s camp theatrics to the nuns’ orgiastic convulsions, was portrayed in the same shrill, in-ya-face mode. Though only a modest success in the U.S., The Devils was a pretty big hit elsewhere, grossing ten times its $1.2 million budget. And no wonder: It was a total freak show, with torture and nudity galore, the religious trappings only heightening its sense of lip-smacking transgression.

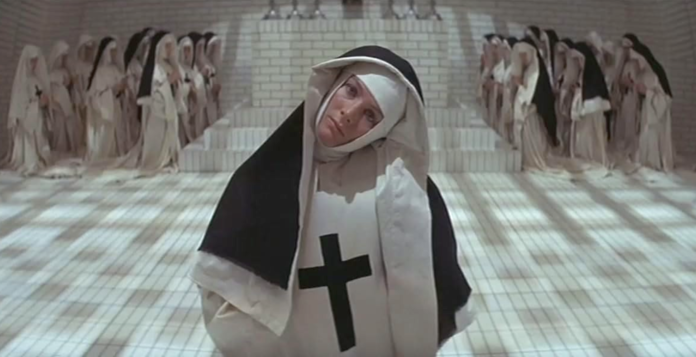

Yet for all its excess, this Devils also has an undercurrent of sobriety that demands more serious consideration than most of the director’s ouevre. He got an uncommonly restrained performance from Reed, even if he sparred with that mercurial actor during the shoot. Redgrave, by contrast, is unrestrained as never before or since (in a role originally intended for Russell’s usual star Glenda Jackson), giving a memorably baroque turn that is not without its pathos. Years later she said she had been disappointed to learn the film would not be shot on historic locations, but in the studio—that is, until she saw the sketches for Derek Jarman’s production design, at which point she realized it would be “something very special.” Those monumental sets, white in a way denoting not so much purity as a morgue, establish an atmosphere of suffocating spiritual and social malignancy. Ditto Peter Maxwell Davies’ dissonant musical score, and cinematographer David Watkin’s arresting compositions.

Though it also won a handful of awards, The Devils was largely excoriated by critics at the time as a carnival of atrocities, a personal violation—they might well have wished Russell burnt at the stake. To get even an X rating (then given to anything considered truly “adult,” including Midnight Cowboy and the aforementioned Clockwork Orange), it was substantially cut in the U.S., U.K., and other territories where it wasn’t banned outright. The most notable casualty almost everywhere being a so-called “Rape of Christ” sequence early on that is Sister Jeanne’s carnal fantasy of a walking-on-water Father Grandier.

Nonetheless, despite all blowback, The Devils was one of those rare mainstream “arthouse” films to actually generate a commercial trend: It kicked off a series of “nunsploitation” flicks just as Fellini Satyricon had sparked a run of sexy toga exercises, and The Night Porter would inspire numerous kinky Nazisploitation knockoffs. (The Criterion Channel is, coincidentally, featuring a nunsploitation retrospective this month that includes Russell’s movie.) Reportedly Warner Brothers is still nervous about releasing the uncut version to American consumers—so this Fri/12’s 7pm Balboa screening may well be your best chance to see it for some time to come.

Corrupted power is also a theme in two new movies arriving this weekend. Andres Veiel’s Riefenstahl is about the (in)famous German filmmaker who lived to age 101, finally passing away in 2003—but she never lived down being Hitler’s favorite director, entrusted with the 1930s propaganda documentary epics Triumph of the Will and Olympia. Originally a successful actress exemplifying the athletic “master race” ideal in the popular genre of “mountain films,” she was unquestionably a brilliant technician and stylist behind the camera. Later she tried to distance herself from the Third Reich, claiming she was just an artist uninterested in politics who would have done “just the same” for FDR or Stalin “if ordered.” But her excuses tend to fall apart in the face of actual evidence: Official records show she was lying in saying she witnessed no atrocities and didn’t know about concentration camps, for starters. Her attempts at reputational salvage never ended. Yet she was her own worst enemy in that regard, utterly unable to accept any culpability whatsoever.

In 1993 there was another documentary about her, The Wonderful Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl—interesting but unsatisfying even at three full hours, perhaps in part because it had originally been commissioned by the lady herself. This shorter work packs considerably more merciless punch. We see her constantly fly into rages during TV interviews (for which she demanded exorbitant pay), hoping to cover over her dubious past by simply shouting denials in response to any uncomfortable question. She is vain, controlling, self-pitying, and occasionally given to racist invective; her Ayn Rand-like aura was heightened by having a long-term lover 40 years her junior. This movie is fascinating, an unvarnished portrait full of rich archival materials in which the subject’s evident talent and intelligence, already tainted by historical context, are only devalued further by the ugliness of her personality. Riefenstahl plays Sun/14 with the director in attendance at the Smith Rafael Film Center in Marin, then opens for a regular run there Fri/19.

Authoritarianism is approached from a very different angle in The Long Walk, which is based on the very first novel Stephen King wrote (though it was not published until 1979, after Carrie, Salem’s Lot, The Shining, and The Stand), when he was a mid-1960s college freshman. Perhaps that accounts for the air of juvenalia around this adaptation from director Francis Lawrence, whose Hunger Games films offered a much more expansive dystopian-future vision of deadly competition amongst youth. Here, 19 years after a “war that tore this country apart,” there’s an annual “race” between 50 young men—one from each state—that ends when only one is left alive. They must keep up a pace of at least three miles per hour, without sleep or pause, for as long as it takes for that denouement to be reached. Which in this case is over five days and three hundred miles of rural heartland road. It’s a literal death march in which lives are eventually claimed by injury, illness, suicide, or even a moment’s addled distraction, with soldiers ready to shoot anyone who falters for more than a few seconds.

Written by JT Moller (Strange Darling), the script stays relatively close to King’s original at least until the end. What disappointing, however, is how little political dimension this ripe metaphor for fascist control has been lent. As if terrified to offend anyone, the whole “totalitarian regime” thing, details about the population’s oppression, and even the time period are all kept as vague as possible. That leaves us with an interesting concept that isn’t developed very interestingly, let alone suspensefully.

Indeed, The Long Walk surprised me by being less of a survival thriller like Hunger Games or The Purge than, ultimately, a sentimental ode to boys’ friendship a la prior King adaptation Stand by Me. It has the added self-importance its life-or-death circumstance brings, but no real depth. The competently played characters remain two-dimensional. It bothered me that David Jonsson’s McVries was a sort of “magic Negro”—he seems to exist only to offer tireless support to Cooper Hoffman’s nominal Average White Boy lead Garraty. Casting Mark Hamill (though he’s barely recognizable) as The Major was a big mistake, in that he seems a cartoon of brutal militaristic authority rather than a threatening exemplar of it. The Long Walk has gotten good early reviews, but while it’s well-crafted enough, I have no idea why—for me, there was ultimately “no there there.” It opens everywhere Fri/12.

Brief mention should be made of two other notable openings this weekend. Oakland native Anthony Lucero’s The Paper Bag Plan is a gentle drama about an aging father (Lance Kinsey), newly diagnosed with cancer, who has to try to map out an independent future for his disabled son (Cole Massie) after realizing he won’t be able to care for him much longer. Like the writer-director’s prior East Side Sushi, this seriocomedy can wax towards the formulaic and innocuous, but it has the warmth of conviction, and good performances—particularly from Massie, who like his character is a wheelchair user with cerebral palsy. It opens this Fri/12 at Oakland’s Grand Lake Theater, plays Thu/18 at Marin’s Smith Rafael Film Center, and also opens Fri/19 at San Jose’s Cinelux Almaden.

A 20th-anniversary rerelease of Jonathan Berman’s Commune chronicles the still-ongoing history of Black Bear Ranch, which a collective of hippies bought (with the financial help of some rock stars) in 1968 Siskiyou County. Its ever-evolving “alternative culture” embraced back-to-the-land self-sufficiency, polyamory, child-rearing, feminism, and brief hosting of a more cult-like parallel group (the Shivalila) until the latter’s behavior became so disruptive, they were basically forced to leave. With plenty of archival footage, and interviews with current and former members including Peter Coyote, Commune underlines that 1960s idealism didn’t die out for everybody. It’s playing several dates in Northern California, some with the director and participants present for Q&A’s, including the Smith Rafael (Fri/12), Rialto Cinemas Sebastopol (Sat/13), and Berkeley’s Elmwood (Sun/14).