During the initial waves of the pandemic, I—like many others—got back into video games. And as I started to make games a regular part of my life again, I wanted to find ways to learn about interesting new releases and cool games from the past that I missed. One day, I stumbled on the podcast Insert Credit, which features three regular panelists in a rapid-fire format that consistently points me towards the weirdest, freshest, cleverest video game stuff.

One of the panelists on the show is Brandon Sheffield, an Oakland-based game developer, former journalist, and head of the indie studio Necrosoft. Necrosoft has released a series of gleefully oddball games over the last decade, from the fanciful puzzle/tower defense hybrid Gunhouse to Hyper Gunsport, which they describe as “cyberpunk volleyball with”—what else?—“guns.”

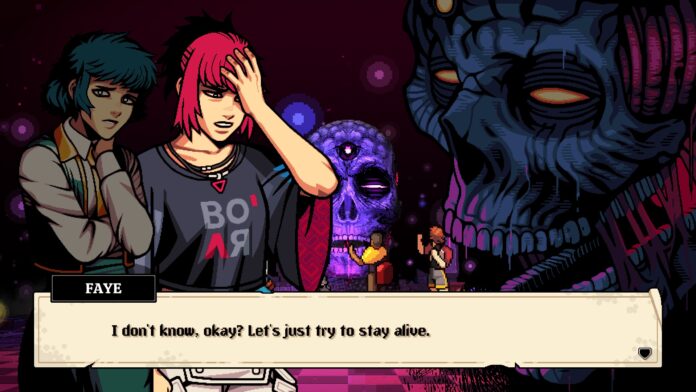

Now, they’re gearing up to release the tactical RPG Demonschool on November 19. Its fast-paced, strategic battles and Giallo-indebted aesthetic indicate that it will be one of the most distinctive releases of the year. (Game description: “Defeat big weirdos in between the human and demon worlds as Faye and her misfit companions, while navigating university life on a mysterious island.”)

After charging through its demo, I was excited to learn more about the game. So I caught up with Brandon via Zoom to talk about the process of putting Demonschool together, the economic realities of game development, and why rent needs to go down.

48 HILLS First, how would you describe Demonschool to someone unfamiliar with the game?

BRANDON SHEFFIELD That’s a tough one, because Demonschool is so niche that it requires some game knowledge to even describe to people. I would say it’s an RPG with tactical battles and a relationship system, and spooky but not scary vibes.

48 HILLS I’m curious about what other games you would use to kind of give people an idea. I know that Persona is the obvious one, but from my understanding, it seems like that’s not quite the thing that you were looking at when you were making it. Is that right?

BRANDON SHEFFIELD Yeah. We were looking at Shin Megami Tensei, which is in the same [franchise] as Persona. We also looked at Valkyria Chronicles, and there’s a game called Black Matrix that was on the [Sega] Saturn and Dreamcast which we looked at a lot. It really started out as something completely different, with the idea of, “What’s the smallest grid tactics game that you could make, with a small number of tiles?” But then we changed it into something else. [Laughs.] When we take an influence, it’s generally as a starting point from which we then have our own ideas.

48 HILLS I was listening to the most recent episode of Insert Credit this morning, and you mentioned that the game had existed in some form since 2017. So I was really curious about how the idea for the game has evolved over time as you’ve worked on it.

BRANDON SHEFFIELD If we had had the money to have a producer and a real preproduction period, we could’ve figured out what the game was earlier on. But because we didn’t have that stuff and we had to pitch [the game to publishers], we had to get as much stuff ready with as little thinking as possible. The game did wind up evolving a fair bit from the initial conception. The battles were much smaller, the interaction with the world was more like a raising sim, and it was all menu-based movement—you didn’t get to run around the world at all. I think if we had been able to have a real preproduction period, we would’ve come to our final conclusion a lot sooner. But it costs a lot of money to not have money. We were also working on Hyper Gunsport from 2019 through 2022, so we were working on it in the background.

48 HILLS You mentioned not having had much of a preproduction phase. Is having a preproduction phase a normal thing for game developers to have before making the game itself?

BRANDON SHEFFIELD I would say that it’s normal for games with higher budgets. For smaller, independent game developers, it can be hard to really have the time to do that. Preproduction necessarily means spending money and time in order to pitch it, so that then you can get funding to make it happen. That’s one thing that differentiates some successful games from some that aren’t, is those that are really able to take the time to figure things out in the early stages.

The other tactic that people can take is to finish their first pass and then put it into early access, and then have people play it while they’re working on it. But that only works for very specific types of games, especially live games [like Fortnite or Lethal Company], and it’s a lot harder with something narrative. We just weren’t making a game like that, unfortunately for us. If we did, we’d be rich! [Laughs.]

48 HILLS I’m curious about how the development for Demonschool was different from Hyper Gunsport or the games you did earlier, like Gunhouse or Oh, Deer?

BRANDON SHEFFIELD In the very early days, it was funded by contract work that I did outside, and then I would pay people here with that money. I have pretty much always been getting bits and pieces from a platform holder like Sony or Microsoft, or from grants or things like that. Because of that, we have worked on our games in spurts—“When we have the money to work on this project, we will, because I’ve secured this chunk of money to be able to do this.” Like, Hyper Gunsport is a pretty small game in the grand scheme, but it took from 2014 to 2020 for the first version to come out. It got cancelled five times, and went through multiple different publishers. Demonschool has been a much more consistent production compared to prior ones where, once Hyper Gunsport was out of the way, we were able to really focus. The game is dramatically better for it.

48 HILLS Turning to the game specifically, there’s a very specific tone to it. I’m thinking about the setting, the combination of 2D and 3D. What was the direction for those tonal or aesthetic choices?

BRANDON SHEFFIELD The tone has been pretty consistent throughout the production. It’s rooted in Italian horror films from the ’70s, which have this kind of interesting duality of beautiful music while something really ugly is happening onscreen, and a lot of practical effects. We were discussing early on, “What does the idea of practical effects in film mean in a game context, when things are all digital?” We came up with the 2D/3D mixture. Quite a lot of our effects are actually 2D sprite animations that are just bent onto an invisible 3D sphere so that it looks like it has dimension.

One of the things I like about practical effects is that I’m always thinking about the work when I see it. It doesn’t take me away from the narrative, but running in the back of my mind is, “Wow. What did they just do there?” When I played Saturn games in the ’90s, they gave me that feeling because it looked like it was so hard to do— like the game is barely holding together. And I really liked that, because it’s an extra point of communication between the people that made the thing and the people that are interacting with the thing.

Aside from narrative, and aside from playing it and having a good time, there’s this extra piece of conversation between developer and player that you can have if they can see the work and if they can wonder about it.

48 HILLS Interesting! Hearing that, I was thinking about how in really big AAA games, the goal is to be as smooth and polished as possible, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but you’re not getting that same kind of feeling.

BRANDON SHEFFIELD The critical thing when trying to approach a project this way is, the player experience still has to be as smooth as possible. Those places where the game is in dialogue with the player—a little roughness or something—that has to be done in a way that doesn’t interrupt the player having a good time. That can be a challenge, but I think we did some of it.

We had been talking about a movie called Blind Woman’s Curse, which is a Japanese movie about a gangster who gets cursed by a witch. In one of the final scenes, the background clouds form a spiral. It looks really cool and fantastical, and it’s not addressed in any way—it’s not the point of the scene. It’s just present for you to discover. And that’s the kind of thing that I really enjoy. In Demonschool, we want people to wonder, what’s around that corner that you can’t see behind?

48 HILLS I want to dig a little bit more into the battle system in particular. It feels like there’s a lot of ideas in conversation with each other: the planning phase vs. action phase, and the grading system, which feels very arcade-y. I was wondering how all of those elements developed.

BRANDON SHEFFIELD Once we were really in production, the goal was to make a battle system that reduces the number of clicks that the player has to do. In Final Fantasy Tactics, or traditional tactics games, you have to select the character, select where they go on this grid, confirm it, select whether they attack or defend, confirm that, and then you select the enemy. Which is a totally fine way to do things, but that’s more zen: It becomes kind of a meditative thing. We wanted to make interacting with it very fast. That was a throughline for the whole project, getting out of the way of the player doing what they want to do. We came up with the idea of moving in straight lines, and then if you interact with an enemy, you do whatever your class of character does.

[We also wanted to be] friendly, in that you can plan out your moves at your leisure, and then you watch it all take place. That planning phase/action phase idea was inspired by Valkyria Chronicles. The action phase was somewhat inspired by Suikoden, where you choose all your attacks and they all happen simultaneously and they can go in different orders. In Demonschool, once you hit the action phase, they don’t necessarily take place in the order that you planned them. They’ll take place in the order that makes it happen the quickest, and winds up being the flashiest as a result.

For a while I wasn’t sure how it was going to go over, but then I brought it over to a friend’s house and her husband was playing it. He was like, “Oh okay, so if I move that guy there, and if I do this…” He was really puzzling through it. I was like, “Maybe it’s gonna work!” [Laughs.]

48 HILLS Yeah, totally!

BRANDON SHEFFIELD The first time I saw someone trying to do it efficiently, I was like, “We should reward that.” That’s where the arcade-y thing comes in. It was hard to figure out how to grade the battles, because there are so many things that we could do that would encourage less-fun play—like, if you deal the most damage. Well, you could deal a lot of damage by just letting enemies continue to spawn, and grinding for a long time. So we came up with a turn limit. If you defeat enemies within the turn limit, then you get an A. Having grades feeds into being in a school, and what you receive as a reward for those grades is what you use to study techniques that give you new abilities in battle, and so we tied it all together.

48 HILLS How long did the process take of iterating to where everything was all linked together? Because it feels very intricate.

BRANDON SHEFFIELD I feel like systems are only worth doing if they complement each other. Of course that also makes things very complicated, because if you change one thing, then everything else changes. So it took awhile. Ultimately, it came down to, “What is the most important thing to communicate, and how efficiently can we do that?” That’s when it coalesced.

48 HILLS I know that you worked as a journalist before you were a game developer. Was there anything about game development that surprised you when you moved from writing about games to actually making them?

BRANDON SHEFFIELD I don’t know if surprise is the right term, but I ran a magazine called Game Developer. I spent eight years or so, every month, editing articles about best practices for game development. So I was like, “I’m not gonna make any of those mistakes when I have my own company.” And then I made so many of the same mistakes. [laughs] Because you just wind up getting sidelined into, like, overscoping [adding too many features into a game], or not nailing down your concept quickly enough. So it wasn’t a surprise, but I was a little disappointed in myself.

But I think the biggest change for me is, when I was running the magazine, I had a testament to what I had done. Every month a thing came out and it was like, “OK, that’s what I spent my last month doing.” Now, with multi-year development cycles, I can lose two months and be like, “What happened? Where did that time go?” That’s something that I really miss, the proof of existence that you get from having something that comes out regularly.

48 HILLS Kind of related, how do you think the industry has changed? On a broad scale, but also just in terms of the Bay Area scene specifically, what kinds of changes have you seen?

BRANDON SHEFFIELD Obviously, the Bay Area has changed a lot. When I quit my job in journalism and started doing game development full-time, all the indie weirdo game devs were here. We all knew each other, we all had weird little dramas with each other, it felt like a big scene. Then, as tech grew and they needed places to live, all the tech folks came out into Oakland, and then all the artists that had left San Francisco to come to Oakland now had to leave Oakland. It just felt like arts were kind of disappearing from the whole area. And it was so gradual that it didn’t feel like it was a big trend until probably around the Ghost Ship fire, and then it felt like there was an endpoint for fun times. I think it’s coming back now, I feel like DIY venues are starting to happen again.

In terms of the game development scene, there’s always been a gap between San Francisco and the East Bay, and that remains present, but I feel like both groups are smaller than they were before. There are fewer of us, and we don’t hang out. [laughs] But we try. I’ve been running an East Bay game dev meetup for 15 years, and we still get new people coming. But it’s very weird to watch things change over time. Because I’m staying in Oakland, this is where I’m going to live. It just feels like things are changing around me.

48 HILLS I mean, you mentioned DIY venues coming back. I’m curious if you think that could make its way into games as well.

BRANDON SHEFFIELD I feel like it’s possible. I think that it’s easier when there’s a natural energy happening, and I don’t know that that natural energy will happen without cheaper rent and a bunch of young people. I can’t build a community like I could when I was in my 20s because I don’t know if the youngsters want to get involved in the same way. The way that I’m thinking about building community is probably very different from the way that someone who is graduating high school right now is thinking about building community. I still want to try to push the things that I can push, but I also want to be ready to support whatever new things are coming along that young people may try to build. And I hope they do, and I hope that I can help facilitate. I can only hope. Rent going down is the only thing that’s going to change it.

48 HILLS What do you hope players take away from Demonschool?

BRANDON SHEFFIELD I like when media inspires you to think about something else, to think about it within the context of your life, if it inspires you to make something else. That would be the happiest thing to me, if someone played this and then they thought they could do something better. This isn’t a game with high-art leanings or pretensions, but I think that low art can really inspire thought as well. Like, when I watch a C-grade movie that has really overambitious effects, or a really neat attempt at a story, and I keep thinking about it even though it wasn’t that good – first of all, I hope our game is good and people do like it. But I hope that people can have that kind of feeling.

Obviously, good movies make me feel that way as well. I don’t have to focus on just the bad ones. [laughs]

48 HILLS Is there anything you wanted to add before I let you go?

BRANDON SHEFFIELD I always put the Oakland Tribune Tower in every game that I make, so people can look out for that if they can find it. And I hope people enjoy it. Our team is split between the US and Europe, it’s a very international and LGBTQIA+ diverse team with a lot of viewpoints and thoughts. Little pieces of all of them are in there. And we’ll just see. You put a thing out, and all you can do is hope.

***

Brandon and I spoke in August, ahead of Demonschool’s original release date of September 3. However, a few days after we spoke, the hotly-anticipated Hollow Knight: Silksong was announced for release on September 4, which caused Necrosoft to push Demonschool’s release further back; Brandon spoke in-depth with Aftermath’s Nathan Grayson about the decision to delay the game. Before publication, I reached out to Brandon via email to see if he had any further comment about the delay, and he responded:

“What I can say about the delay is that we were able to add a lot of things that we wouldn’t otherwise have been able to, like more detailed romance sequences and a lot of quality of life features, so even though it wasn’t what we wanted to do, I think it was a net positive in the end.”

DEMONSCHOOL is available November 19th on Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 4/5, Xbox One & Series X/S, and PC. More info here.