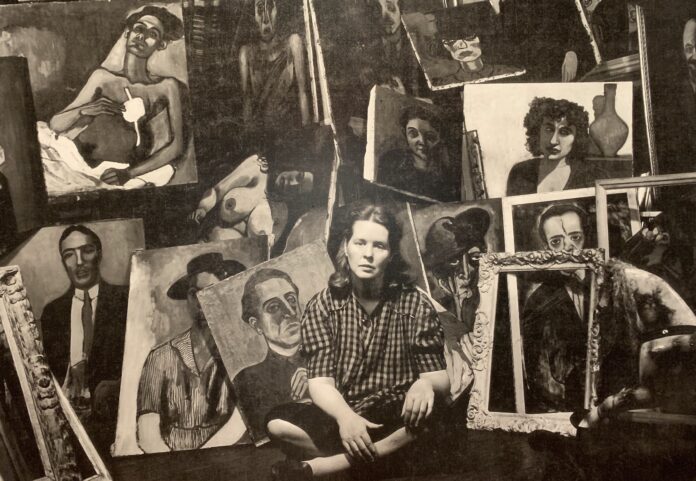

“Alice Neel: People Come First” (through July 10 at the DeYoung Museum, SF) is a 60-year retrospective of the paintings of American communist and figurative painter Alice Neel (1900-1984). The exhibit makes its way to San Francisco after first appearing at the New York Metropolitan Museum and the Guggenheim Bilbao.

Born at the turn of the century to a middle-upper class family in Pennsylvania, Alice Neel’s early life was marked by catastrophe: an “alienated” childhood; the death of a daughter from diphtheria; a series of bad lovers, one of whom abducted her sole surviving child (“the end of everything”) and another who destroyed 300 works of her art. After a nervous breakdown, Neel spent one year in a mental institution.

Throughout it all, she painted. “I had a very hard life, and I paid the price for it, but I did as I wanted.”

Less concerned with selling her art than being recognized for it, and less concerned with relevance than with capturing specific political-historical moments, Alice Neel produced hundreds of works over her lifetime. Despite little formal participation in the art movements of her time, Neel’s paintings of figures both public and private comprise one of the largest collections of portraits of the 20th century.

“I want my portraits to be specifically the person and also the Zeitgeist,” Alice Neel said. “I believe in art as history. The swirl of the era is what you’re in and what you paint.”

In the 1920s, Alice Neel painted street scenes in Havana. In the 1930s, she painted dock workers on strike and a series of male nudes. In the 1940s she painted her Black and Puerto Rican neighbors in New York’s Spanish Harlem. In the 1950s and 1960s, she painted literary critics, communist intellectuals and a series of pregnant women and mothers. In the 1970s, her subjects were feminists, gay and trans couples, and Andy Warhol, in recovery after being shot by Valerie Solanas. In 1981, she became the first living American artist to exhibit their work in the Soviet Union.

Neel found economic and artistic stability through employment in the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The Federal Art Project, the New Deal program that employed some 10,000 American working artists and writers gave many successful artists, such as Jackson Pollack, Mark Rothko, and Willem de Kooning their start—painter Lee Krasner called the program “a lifesaver” for working artists in the Great Depression. Under the WPA, Neel submitted one painting every six weeks for almost a decade. Later, patronage from her peers helped her continue making art as a single mother to two young sons.

While many artists of the WPA era eventually discarded social realism for the more apolitical abstract art trends that predominated in the 1950s, Neel managed to unite the two movements in her transition to the portrait format for which she became famous. In fact, more than any other artist of the time, it is Neel’s oeuvre that most complicates the accepted art historical narrative of the 20th century: that social realism became boring, doctrinaire, and politically irrelevant, so artists were forced to innovate by turning inward towards “pure abstraction.”

Neel’s work overcomes the contradiction between social realism and abstraction. Her paintings are honest and accurate depictions that are also expressionistic and gestural with a quality that could be considered sloppy. Many of her portraits have in common a broad-brush outline of indigo blue, a kind of stylistic and symbolic stand-in for a thread that binds all of humanity together. If Neel’s work is outwardly oriented it is also deeply personal, touching upon the singular inner psychology of her subjects.

“Perfectly legitimate subjects”

One of Neel’s most moving portraits is that of Ella Reeve “Mother” Bloor at her open casket public funeral in Harlem. Bloor was a labor organizer and one of the most prominent and high-ranking women in the Communist Party USA. In the painting, the “Red Feminist” is attended by a ribbon of mourners and flanked by a bough of pink and red flowers.

In the 1960s, Neel began painting pregnant women. Typically excluded from portraiture, Neel considered pregnant women—like her male nudes of the 1930s—”perfectly legitimate subjects.” Neel may have been inspired by the pregnant nudes of photographer Imogen Cunningham. Neel also appreciated the resistance of her pregnant subjects to sexualization, saying “a pregnant woman has a claim staked out; she is not for sale.” Indeed, the subjects in this series are arresting in their self-possession.

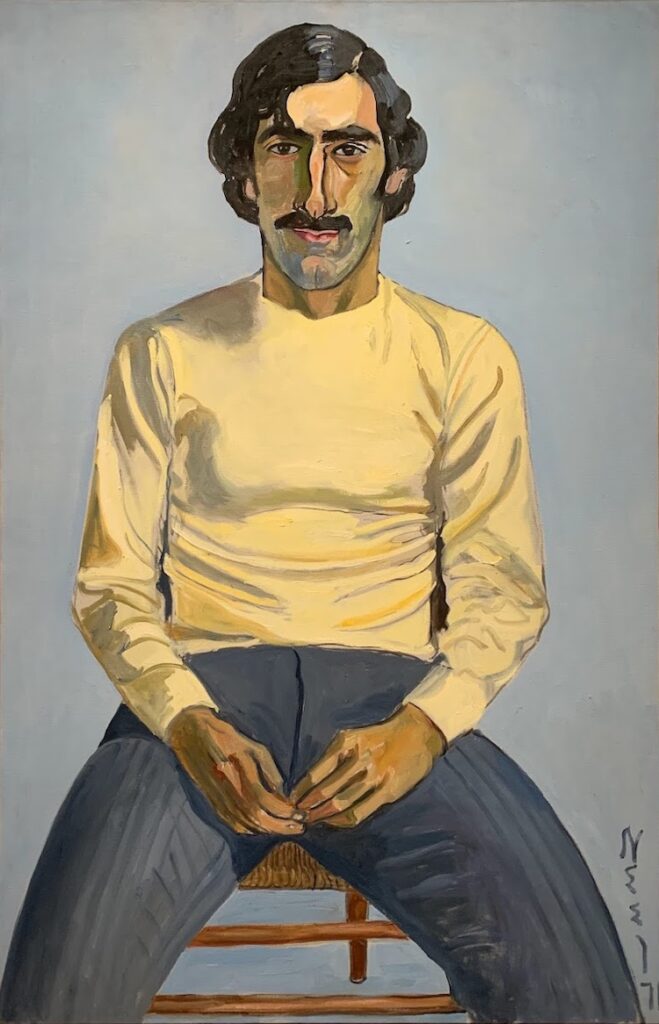

Neel also captured many important figures in the burgeoning women’s movement and gay scene. Her portraits of remarkable young gay men, such as the San Francisco pianist Robert Hagopian, are especially moving, as many of these paintings have served as memorial tributes to subjects who later died of AIDS. Gay and trans individuals as well couples are captured by Neel, again as natural and easy subjects. Neel’s title for one of these works, “Jackie Curtis as a Boy,” underscores her advanced understanding of the performative and fluid nature of gender.

But not all of Neel’s portraits are so affirming. One of the most shocking of Neel’s paintings is the rendering of her own son, Richard in “The Corporation Enslaved All These Bright Young Men.” Rendered in a sickly, gangrenous green hue, her son looks impassively to the outside of the frame in seeming acquiescence to his part in the capitalist machinery. And still, the portrait reveals something profound about the dialectical relationship between mother and son.

Alice Neel was a committed communist and her son was a Reaganite. Yet he posed for Neel’s portrait knowing how she might represent him. He has championed his mother’s work. He helps preserve her apartment as a kind of living museum at 300 West 107th St. in New York City. It was his encouragement that convinced Neel to finish her last self-portrait, painted at 80-years-old, nude.

Neel’s portraits, or “pictures of people” as she preferred to call them, are nothing if not honest.

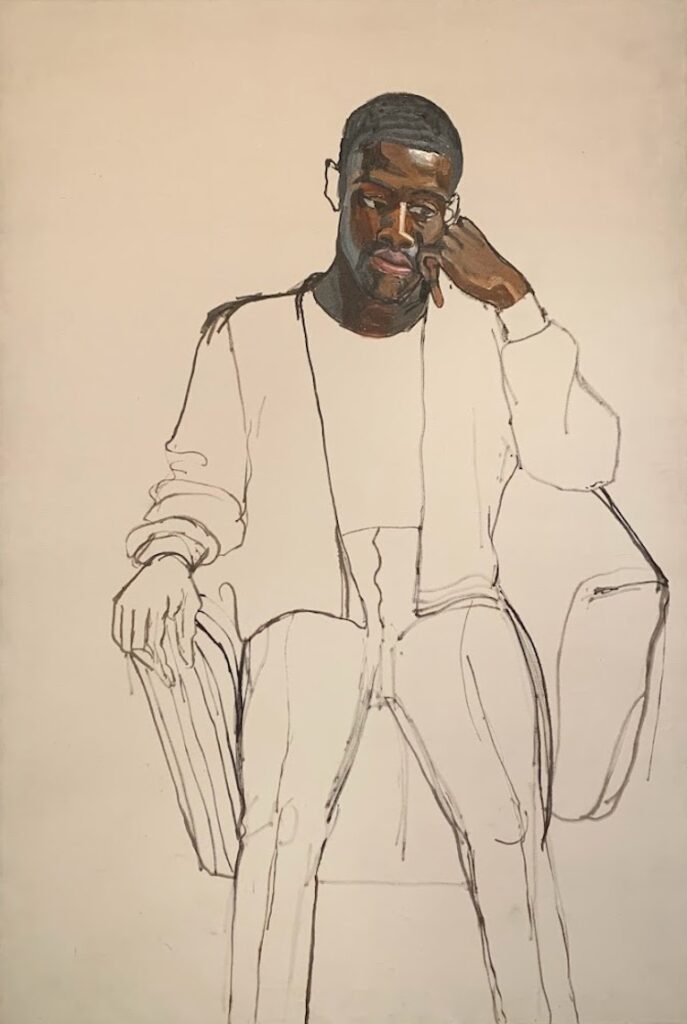

The final, and most affecting, painting in the exhibit is “Black Draftee”: a portrait of James Hunter, a young man Neel met on the street and convinced to be painted in his final days in New York City before being drafted to Vietnam. The progress that would have been made in a second sitting is reflected in the thick outlines of his body below a delicately rendered face—Neel seemed to have known that she may not see him again. Indeed, he did not return. Her subject is on the cusp of manhood. With his gaze to the distance and his head in his hands, he contemplates his future with an outward awareness that his fate is uncertain.

(When, two years later in 1967, Muhammed Ali faced his own induction to fight in Vietnam he asked, “Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go ten thousand miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights?)

Unlike many of Neel’s other portraits, which are by turn playful, contemplative, or even melancholy, “Black Draftee” is a painting that is genuinely painful to behold because of its half-realized state (and as an aside, is a perplexing choice for the cover of the notebooks for sale in the museum gift shop). The portrait is nothing short of tragic—in it, we see a life being cut down before our very eyes.

This country’s project (if you can call it that) of realizing full personhood for every human soul, is a project that remains unfinished.

Pending a revolution, Alice Neel painted.

ALICE NEEL: PEOPLE COME FIRST shows through July 10 at the DeYoung Museum, SF. More info here.