If ever an entire film festival merited being put in a time capsule to provide evidence for coming generations, that would probably be UNAFF, the annual United Nations Association Film Festival (Thu/16-October26). Its 28th edition puts that role up-front, having been given the blanket theme “Messages for the Future.” Needless to say, the future is looking pretty shaky on numerous fronts at present. But this event’s emphasis on nonfiction movies focused on human rights issues around the world more often than not manages to go beyond indictment to provide inspirational models in the past, and activist solutions for present-day woes that threaten our collective tomorrow.

The 11-day festival features 60 shorts and features, at least half of them directed by women and POC. There are contributions from and/or about Mongolia, Rwanda, Georgia, Iran, Luxembourg, Mali, Turkey, Afghanistan, Congo, Sudan, Cambodia and numerous other countries, not excluding such expected political hotspots as Ukraine, Palestine, Israel, Hungary, and the US.

The program begins Thu/16 with the world premiere of Judith Ehrlich’s short An Ordinary Insanity, about famed whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg’s long campaign against the nuclear threat. It plays with Chip Duncan’s hour-long Stand Together As One, a look back at the catastrophic famine of the early 1980s in Ethiopia; and Susanne Rostock’s feature Following Harry, which pays tribute to the lengthy career and high-profile civil rights activism of singer Belafonte, who passed away two years ago at age 96. These films all play at the Mitchell Park Community Center in Palo Alto.

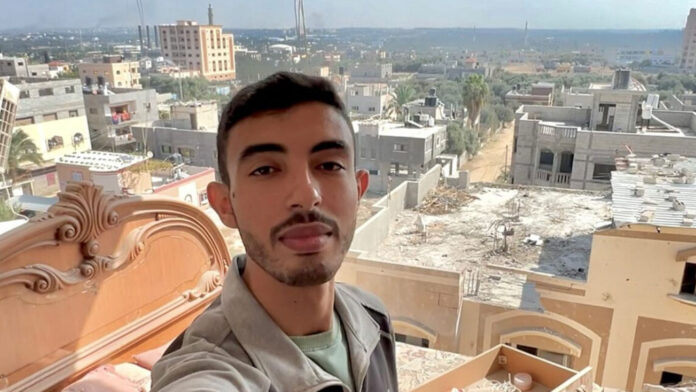

Most of UNAFF will be held at that and other locations in the South Bay, also including some free shows on the Stanford University campus. But there are two nights at SF’s Delancey Screening Room on the Embarcadero. Wed/22 brings a double bill of half-hour portraits: Abdullah Harun Ilhan’s Free Words: A Poet From Gaza provides an introduction to Mosab Abo Touha, the Palestinian writer turned refugee who’s won an American Book Award (for a collection published by City Lights); Berkeley-based duo Alan Snitow and Deborah Kaufman’s Post Atlantic regards the art and life of Hunter’s Point-raised African-American painter Dewey Crumpler. That longtime San Francisco Art Institute teacher’s murals, canvases and multimedia works often engage intensely with minority oppression and resistance in US. history. The next evening will feature another tribute to an artist, Julie Colleen Rubio’s The True Story of Tamara De Lempicka & The Art of Survival. It celebrates the extraordinary Polish expatriate revered for the sharp-edged glamour of both her art deco images and flamboyant, bisexual lifestyle; a major posthumous retrospective at the Legion of Honor closed a few months ago.

Many of the above filmmakers are local, and many represented in UNAFF will be present at their screenings. Among other Bay Area subjects of particular note are David Fiore’s A Little Fellow: The Legacy of A.P. Giannini, about the Italian immigrant who founded the Bank of Italy in 1904 SF, played a significant role in rebuilding the city after the ’06 earthquake, and much more—all while maintaining a community-minded stance (he actually opposed high personal wealth) most unusual amongst bankers. Connie Field’s Democracy Noir, which we previously wrote about here, charts the fight against white nationalism in Hungary; Jessica Zitter’s The Chaplain and the Doctor records a professional alliance at Oakland’s Highland Hospital. For full schedule, location and ticket information on the 28th United Nations Film Festival, running Oct. 16-26, go here.

A couple new theatrical releases:

Urchin

One of the most impressive young British actors to emerge in the last decade, Harris Dickinson makes an auspicious directorial bow with this drama, which both honors and transcends the UK tradition of bleakly realistic working-class depictions a la Ken Loach and Andrea Arnold. We first spy Michael (Frank Dillane) as an inert lump on the sidewalk, one that grouchily reveals itself to be a scruffy, passed-out young man when he’s involuntarily woken by a street evangelist’s spiel. A homeless addict, Mike is not above mugging a Good Samaritan who goes out of his way to help him. But that act gets him thrown into prison. He emerges seven months later sober and much healthier-looking, seemingly determined to staying out of trouble. His social worker gets him temporary housing at a hostel, and he gets himself a job in a restaurant kitchen.

But as relatively well-adjusted as he now appears (helped by listening to self-affirmation tapes), Mike remains on unstable ground—it doesn’t take much to topple him over. Employment, housing, even a new girlfriend (Megan Northam as Andrea) are all things he finds difficult to hold onto, and one suspects from his acts of self-sabotage that on some level he doesn’t think he deserves them. We never do find out just what his backstory is. At one point he mentions having adoptive parents who are “nice,” but “it’s complicated”… meaning that he really has no safety net of people or resources he can turn to, beyond the government’s limited assistance. Inevitably, he is going to freefall, hitting rock-bottom again.

Can he still be redeemed? It is a measure of Dickinson’s complex take on this superficially simple, barely plotted hard luck tale that we’re left unsure—not just whether Mike can be “saved,” but whether it even ultimately matters. The writer-director periodically interrupts this otherwise very gritty story with fantastical, surreal sequences that are inexplicable (are these scenes from Mike’s dreams? the scarred landscape of his soul?) but striking, and make some kind of subconscious sense. When the entire narrative leaps into mystical ambiguity at the end, we’re left with plenty of questions. But we don’t feel frustrated or cheated, because the film has earned such transcendental ambiguity—it is, improbably, a little bit Tarkovsky as well as a whole lotta kitchen sink realism.

Dickinson himself appears briefly onscreen, but this is no vanity project. He gets excellent, entirely credible performances down the line (Dillane is quite remarkable), and achieves sequences of sudden joy or anger that are stylistically bold, yet entirely in the service of character. Some may find Urchin too much of a downer, or too lacking in conventional explication. It’s not a perfect movie, but it has a discipline and energy that announce a fully-formed talent—and its dramatization of lives slipping off the margins is refreshingly without condescension, or cliche. Mike isn’t an entirely likable or even understandable person, yet we feel like this film does justice to a figure who’d probably be relegated to the background of any other screen story. Urchin opens Fri/17 at SF’s Roxie and AMC Metreon.

If I Had Legs I’d Kick You

Beleaguered in entirely different ways—well, there’s a certain overlap in terms of substance abuse and “homelessness”—is the heroine, or perhaps antiheroine, of writer-director Mary Bronstein’s feature. Linda (Rose Byrne) is a 40-ish woman living on Long Island with her husband and child. Only her husband seems perpetually away on business, while the approximately seven-year-old daughter has some unspecified illness that requires intubation and 24/7 monitoring. Linda almost never has a moment to herself, and isn’t coping well—she’s sleep-deprived, wine-guzzling, open to any other mind-altering chemical, pressured on various fronts, angry at everybody.

That includes her therapist (former late-night TV host Conan O’Brien, a casting leap that completely works), and we are shocked to discover that this walking trainwreck is, herself, also a therapist. Her patients are a lineup of variously disturbed and/or self-indulgent individuals, notably Danielle Macdonald as a neurotically unfit mother. Linda’s own offspring needs to gain weight to proceed to the next stage of her medical treatment, as doctors keep reminding mom.

As if all these weren’t stresses enough, one night water on the floor leads to discovery of a home ceiling leak that abruptly collapses into a gaping chasm—one that to Linda’s addled eye, at least, appears some sort of disorienting, cosmic black hole. As attempts to repair the house drag on, she and the daughter must move into a nearby motel, which adds yet more elements of chaos to their lives.

Legs was inspired by Bronstein’s own experience some years back of dealing with a child’s serious health crisis. But this is no inspirational, TV-movie-like exercise in brave tears and viewer empathy. As written and played, Linda is astringent, argumentative (often on the phone with her exasperated husband), expectant of help but ungrateful when she gets it, a fountain of bad decisions and behaviors. We understand she’s in a near-impossible situation—but still, she seems the kind of person whose reactions to problems are guaranteed to make them worse. The director plunges us right into her rattled, bad-vibes mindset, relying heavily on closeups, while conversely keeping some characters (notably the daughter and husband) heard yet almost entirely unseen. A lot of this is played for edgy comedy, with a side serving of what might be termed existential sci-fi re: that mysterious ceiling hole.

This is a distinctive piece of work, concisely executed on every level, with some really witty writing—a particular beneficiary of that is rapper A$AP Rocky as the motel superintendent who becomes Linda’s friend, sorta. (She doesn’t exactly seem the type to have “friends.”) All the dialogue here is sharp, in the cutting as well as intelligent sense, but his is particularly sparkling. Yet original as it is, it’s hard to know just what to make of If I Had Legs—while always interesting, its point is elusive. We never glimpse who Linda might have been before all this befell her, so there’s no psychological or real-world context to ground us. These two hours of frenetic idiosyncrasy feel untethered to any emotional terra firma… though if you had or gotten near a nervous breakdown of late, you may feel otherwise. If I Had Legs I’d Kick You opens in SF Bay Area theaters (specific venues were TBA at presstime) beginning Fri/17.