When Roddy Bottum first moved to San Francisco in 1981, he didn’t have a plan, a job, or even a particularly defined reason for coming here. He was 17, newly unmoored from Los Angeles, and soon found himself living above the original Rainbow Grocery (16th St. between Valencia & Guerrero) in a cheap, scrappy apartment full of people who were making art because they didn’t know how not to.

Days blurred into nights, music equipment passed hand to hand, and half-eaten burritos littered the floor. The city outside their window seemed to run on its own strange frequency. It felt less like moving to a new town than stumbling, by accident, into a fully-formed community whose rhythms were already awaiting him.

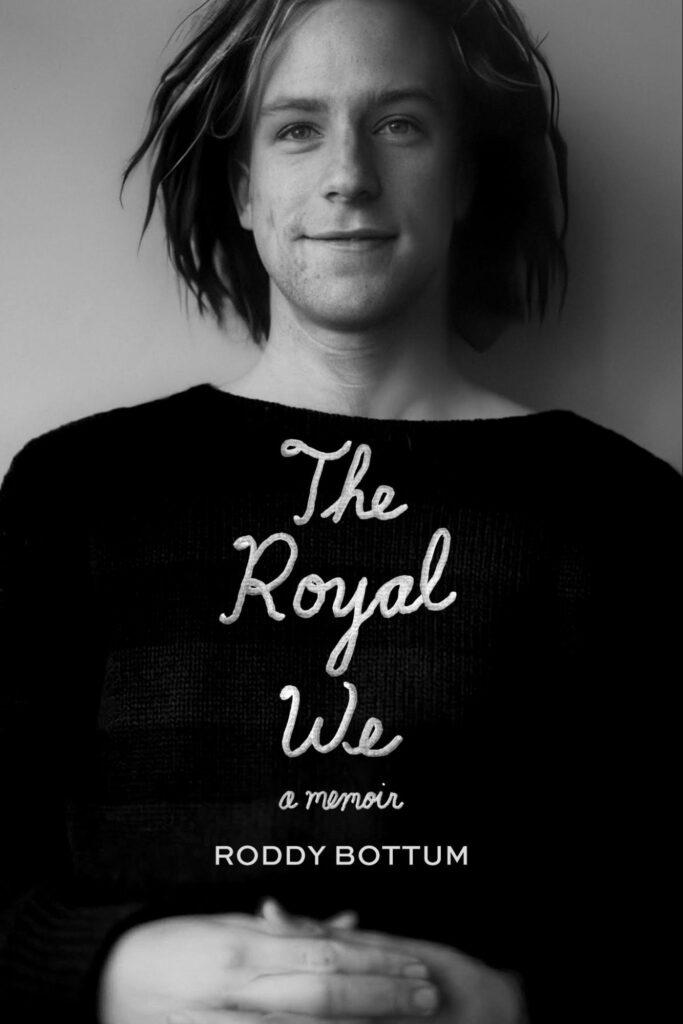

That feeling—of arriving in a place that shapes a person before they understand how—runs through Bottum’s new memoir, The Royal We, which he launches locally with a party at City Lights Books on November 20.

While it wasn’t all puppy play and rainbows, the musician, who’d eventually find fame with Faith No More and Imperial Teen before relocating to New York in 2010, looks back on that formative period in San Francisco as nothing short of a privilege.

“The book is a story about San Francisco—the time and place, and my place in it,” he told 48 Hills from Paris. “It feels like it was such a special time, different from any other. My community just all happened into that city at the same time, and it felt like a sense of royalty in that we all got to live through what San Francisco was at that point.”

Leaving LA was instinctive for the future indie musician, who found its cookie-cutter mentality, obsession with beauty and glamour, and the entertainment industry off-putting.

“I was a darker kid than that, and I aimed for something a bit more intense,” says Bottum. San Francisco was the opposite. If LA was bright flood lights on Hollywood Blvd., the City by the Bay was the underside. The weather was gloomy, the people looked spookier, the drugs were merciless, and the music was melancholy.

“All of a sudden, there were goth kids, which I’d never seen before,” the musician says. “And I’m obsessed with dark, political themes. There was politics, whereas Los Angeles lacked all of that.”

Inside the apartment above Rainbow Grocery, everything was porous—ideas, noise, bodies, and routines. “I was living with people outside my family for the first time,” says Bottum. “It was a very vulnerable and formative time in my life. So all of us at that age were sponge-like.”

Billy Gould—who would later join him in rock band Faith No More—was part of that core. The two were as thick as thieves, working closely on music projects in that tight little space. After Gould purchased a four-track recorder, their shared world expanded immensely.

Outside their door, San Francisco felt small, connected, and self-sustaining. Bottum describes it not as an emerging metropolis but as a “village,” a place where artists, punks, queers, and wanderers recognized one another by instinct. The geography reinforced it: Rainbow’s 16th Street location sat at the intersection of the Castro, the Mission, and SoMa.

“In that way, it’s a village,” he says. “It’s tiny, easy to get around, and a really great transportation system connects everything. We were all mobile and connected.”

But the version of queerness Bottum encountered in the Castro was not immediately liberating.

“When I moved up there in 1981, that’s what gay was to me,” the musician remembers. “Castro clones: a very Freddie Mercury look… white T-shirt, jeans tucked into high black boots… that freaked me out.”

Coming from Los Angeles, where he was already resisting prescribed identity, the uniformity was suffocating. “I didn’t have any role models,” says Bottum. “It kept me from exploring my openness about being gay for a long time because if that’s what gay was, I didn’t want to do it.”

It took time to find the queerness that felt like home. That came in the form of drummer Patty Schemel from Hole, the first person he met who was openly gay and also played rock music.

Meanwhile, another San Francisco existed beneath the visible one—bathhouses, alleyways, Buena Vista Park, and the library bathroom at San Francisco State—where queers could meet clandestinely for sexual encounters.

“When I was going out and cruising, it wasn’t about being seen,” says Bottum. “It was the opposite of being seen. It was very covert. I was having sex, and it was my own little secret.”

That secrecy, he says, became muscle memory. “More than anything, it encouraged me to continue that behavior, because later on, when I got into heroin, it was an easy transition,” says Bottum. “I’d already been hiding something for so long.”

Then came the pandemic. Bottum was just on the edge of discovering himself when AIDS began cutting through the city. “There was now a potential death sentence,” he says. “That crisis heightened the taboo of being a gay man.”

He remembers being sure he had HIV after he developed a gnarly pilonidal cyst in his butt crack, long before he could confirm otherwise.

“We didn’t know how the virus spread,” says Bottum. “It was a scary place to be.”

Fear and shame became formative emotional currents—but not permanent ones. Over three decades after coming out in 1992, he says he now feels “unabashedly joyful” about living in his truth.

Writing his memoir during Trump’s first presidency, as COVID took hold, meant turning toward the truth rather than away from it. He even includes a childhood fantasy of being molested by a priest—a symptom of his shame and hunger for intimacy, and an example of the strange ways desire gets shaped when one’s growing up queer with no safe mirrors.

“A big part of the process of being so honest and provocative is to combat that loudness from the Right,” he says. “The more provocative, shocking, and honest I can be with my truths, the better the world will be for it.”

Whether moving to San Francisco, transitioning into queer indie-pop outfit Imperial Teen, working with Crickets, JD Samson, Nastie Band, and Man on Man (a band with his partner, Joey Holman), or writing The Royal We, the musician has always been chasing a pure expression of self.

San Francisco has also changed, but Bottum’s sensory map of it has not. The bicycle messengers and the anarchic street symphony may belong to a different era, but if the musician takes a walk through the Tenderloin or around 16th Street or 24th Street BART these days, those places remain the same to him.

Today, he lives in New York, tours, writes, collaborates, and improvises his life forward. While his new apartment gets readied for move-in, he’s been roaming around the world. Today he is in Gay Paris. Tomorrow, who knows?

“For the next five months, I’m not really sure what I’m doing,” he says. “It’s a vast open horizon right now, and it’s fun not to have answers.”

RODDY BOTTUM / LAUNCH PARTY FOR THE ROYAL WE November 20. City Lights, SF. More info here.