It’s not often that you hear raucous laughter coming from inside an art gallery. I can think of few artists whose work provokes even a chuckle, let alone the giggles emanating from Casemore Kirkeby on a recent Saturday afternoon. One in that rare group is certainly Lindsey White, whose exhibition How to Get on Cable Television is on view through Sun/31.

Lindsey White has long explored the dynamics of humor in her work. Can art even be funny? Is it OK if you laugh really hard inside a museum or gallery? Encounters with White’s work enliven an intellectual spectrum that, in a pleasant surprise, allows whimsy to co-exist with criticality.

For How to Get on Cable Television, White sourced images from photographic negatives in the American Museum of Magic, which houses over 20,000 photographs in its archives. Continuing a long engagement with performers of magic and stand-up comedy, the exhibition delves into the gender dynamics of those worlds. Historically fields that center white men, White’s instead brings women to the fore and re-imagines an archive in which women are as historically recognized.

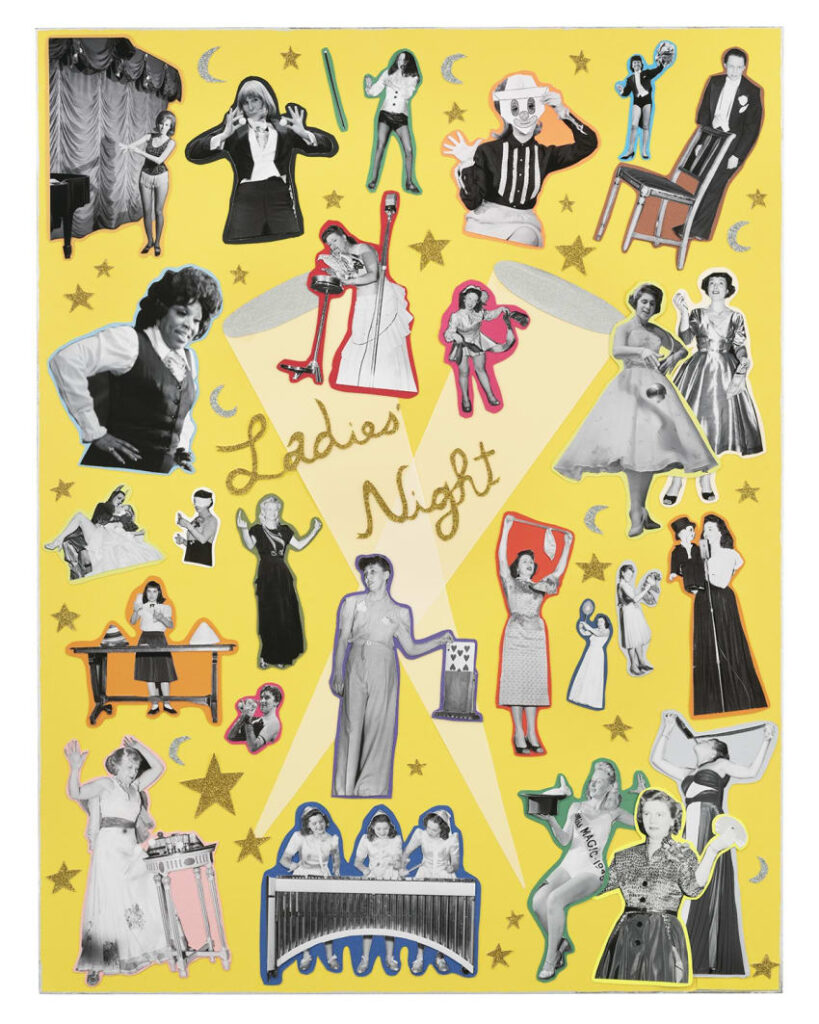

Fan Girl Dream is a collage of black-and-white images of women performers surrounding the words “Ladies Night” written in cursive using gold glitter. It recalls the lockers and bedroom walls that functioned as scrapbooks for a teenager’s adorations and aspirations, underscoring a deep respect for the performers pictured and another possibility for who this teen could look up to.

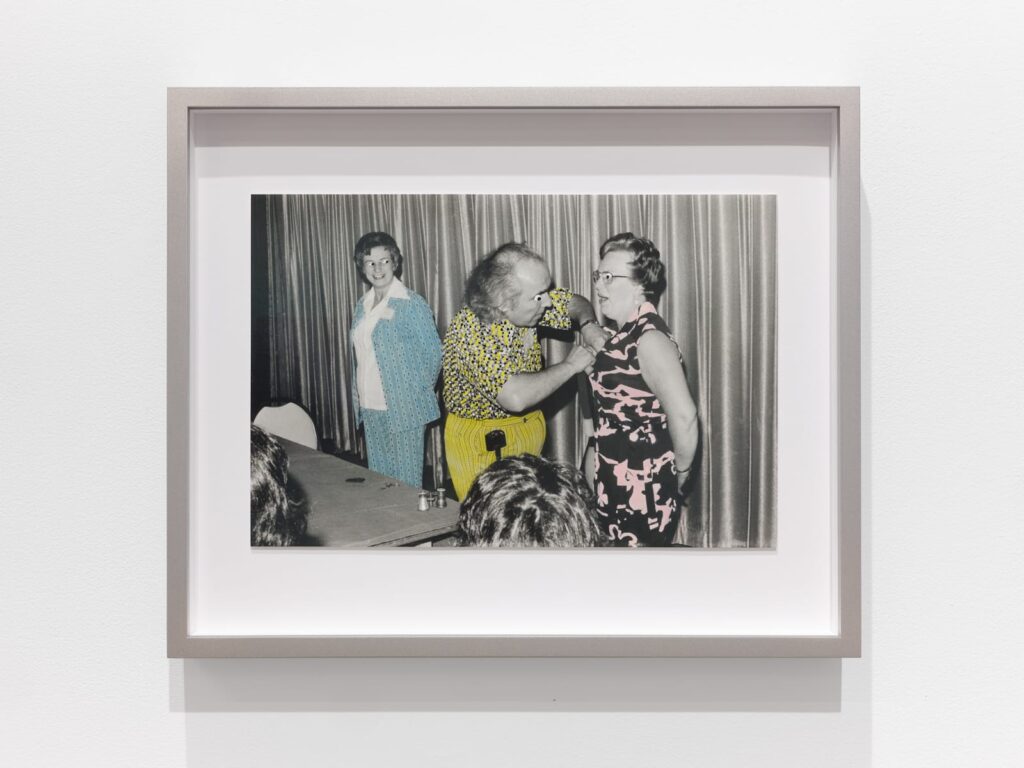

Performance is inherently a multi-directional relationship between audience and performer. But what is the balance of power in these interactions? Does it lie with the person onstage or those seated in the house? Who is made vulnerable and why? Volunteer, an archival photograph altered with gouache paint, calls attention to these power dynamics. Three figures stand in front of a curtain, with hints of onlookers at the lower edge of the photograph. A smiling woman looks on as a man reaches down into another woman’s neckline, an expression of (hopefully mock) surprise on her face.

Who is the audience volunteer in this photograph, and who is the performer? Who is the woman on the left—an assistant perhaps, and to whom? Who requested that hands reach into the woman’s clothing? These ambiguities in Volunteer echo Yoko Ono’s 1964 performance Cut Piece, in which spectators were invited to come onstage to use a pair of scissors on the artist as they chose. In both Cut Piece and Volunteer, we are confronted with the murky trust that both viewer and artist share with one another.

How to Get on Cable Television aptly posits analogies between performers like magicians and comedians with visual artists. It initially might seem to be a disjointed pairing: what could a painter have in common with a stand-up comic? Both groups do share the often-dizzying contradictions of working for an audience (whether onstage or inside a gallery), while contending with the fears and anxieties that accompany any public attention.

Along this thread, White presents three photographs of contemporary Bay Area artists: Bessma Khalaf, Kate Rhodes, and Christine Wang. Clad in costumes (a crow, a hairbrush, and a fly), the portraits tap into the vulnerability and courage it takes for any artist to share their work. To be critiqued, reviewed, rejected. Like a performer contending with heckling (or worse – bombing), artists are encouraged to “brush it off” (as Rhodes’ portrait declares with a resigned grin).

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

There are even hecklers in the gallery, presented in the form of small squirrel figurines, collectively entitled Naysayers. These jeering commentators hold signs bearing derisive text like “that’s different,” “3.5/10,” and “lacking content.” Ouch. These Naysayers also seem to appear out of nowhere at various heights on the gallery walls, like an internal voice that shouts insecurities when you least expect it.

Pardon Me, Please/Stop Looking at Me points to the contradictory desire for and repulsion towards attention. The formidable sculpture stands in the center of the gallery; a line of aluminum buckets bears the title phrases imprinted on opposing sides. “Pardon me, please” has a double meaning of seeking notice, while also apologizing for taking up space. In contrast, “stop looking at me” evokes the internal contradiction among many creative people who want or need eyes on our work, and also desperately want to retreat into the safe, cave-like depths of our studios and away from the social whirlwind of “the art world.”

Art, like comedy and performance, can be the mirror that reflects and challenges who we are and want to be. In moments when this can all feel a bit gloomy, the genius of White’s work is her ability to make us think critically and still create a much-needed space to laugh.

LINDSEY WHITE: HOW TO GET ON CABLE TELEVISION runs though Sun/31 at Casemore Kirkeby, SF. More info here.