In a YouTube interview with the California College of the Arts, artist Maia Cruz Palileo says most of the titles for their shows come from letters from their grandmother.

That’s true of the show at the Wattis Institute, Long Kwento. (Kwento means story in Tagalog). Palileo asked their grandmother to tell the story of her life, but she was a little shy, Palileo says, and after a little bit would write, “Oh, long kwento, I’ve talked too much.”

Palileo is telling her grandmother’s story with paintings and sculptures at the Wattis. Besides colorful family history, the show’s inspiration comes from going through the archives at The Newberry Library in Chicago, which has several Filipino collections—including the archive of a colonial administrator in the Philippines, Dean C. Worchester.

“Long Kwento” curator Kim Nguyen says with the work, Palileo has recontextualized the history.

“Maia has integrated oral history and memory and photographs of their family’s life and their arrival in the United States,” Nguyen said at the show’s opening. “It offers an alternative narrative.”

Many of the histories of the Philippines was written by the Spanish and the Americans. Palileo found inspiration and a different point of view looking at the paintings of Damián Domingo, known as the father of Filipino painting.

“I think the thing that stood out to me the most with those was that I got a sense there was a pride and care,” they said. “There was a consideration.”

Worchester’s photos stand in contrast to that. Worchester, who studied zoology, went to the Philippines twice on zoological expeditions. He felt this was enough to make him an authority, and at the start of the Spanish American War in 1898, he gave lectures and wrote articles about the country and how the United States should control it. He used his photos of indigenous people to try to influence Americans to share his beliefs.

Not surprisingly, Worchester’s photos made Palileo angry, and that anger was part of what fueled these paintings.

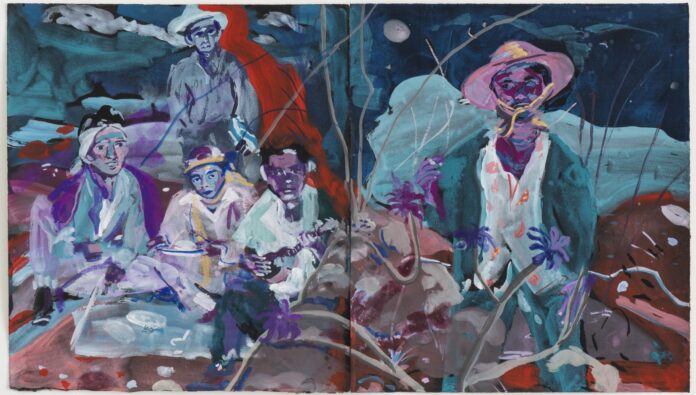

“Here was this dude forcing this narrative on people,” Palileo said. “There was this indignant feeling that I had that was like, ‘No, no, no, you can’t get away with that.’ I’m going to change the story a little bit. I’m going to take those people out and I’m going to put them in a different situation.”

Palileo’s paintings, such as Gabi (night), and Wind, Water, Stone, are dreamy, lush, vivid, and expressive, with loose brushwork. Along with making the history their own, Palileo wanted to show how time isn’t always linear, and honor what’s not there as well as what is.

When Palileo came to see the Wattis, the skylight and the largeness of the space struck them, and they wanted to make paintings on a large scale. At the same time, Palileo was researching a site for a public art project that overlooked a cemetery, and the vastness of that space impressed her as well.

“I learned that the cemetery had become overgrown with branches and trees and leaves,” they said. “That stuck with me this idea of figures appearing and disappearing in landscapes, and also the idea of what is visible and what is not visible and what happened on this land before what we can see and how do we honor what we can’t see in addition to what we can see.”

Working on large works made them think about painting differently, Palileo says.

“What I love about painting is that it can be an act of care, and it’s very physical and sensual,” Palileo said. “Especially at this scale you’re moving your whole entire body. “

Nguyen thinks Palileo’s paintings contain multiple realms and dualities.

“These works hold so much simultaneously,” she said. “They are beautiful and lush and familial and intimate, and also they can be violent or scary.”

Palileo says they are looking forward to her cousin, Dahlia Nayar, a choreographer with the Uh Oh Trio, doing a multimedia performance at the Wattis on December 3 and 4, the final days of the show.

LONG KWENTO runs though December 4 at Wattis Institute, SF. through December 4. More info here.