1974 was probably the peak of “New Hollywood,” even if several of the year’s most successful films were the relatively old-fashioned, all-star likes of The Towering Inferno and Murder on the Orient Express. The movies we really remember, however, were all adult dramas: Chinatown, Godfather Part II, Woman Under the Influence, The Parallax View, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, The Conversation, Lenny, The Sugarland Express, even Zardoz.

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg in what was a fairly incredible celluloid year, around the world. Star Wars was still in the future; films for kids were considered a wholly separate thing, and in truth not much considered at all. Disney was at a low ebb, the year’s biggest G-rated hits being critter-centric indie productions Benji and The Life and Times of Grizzly Adams.

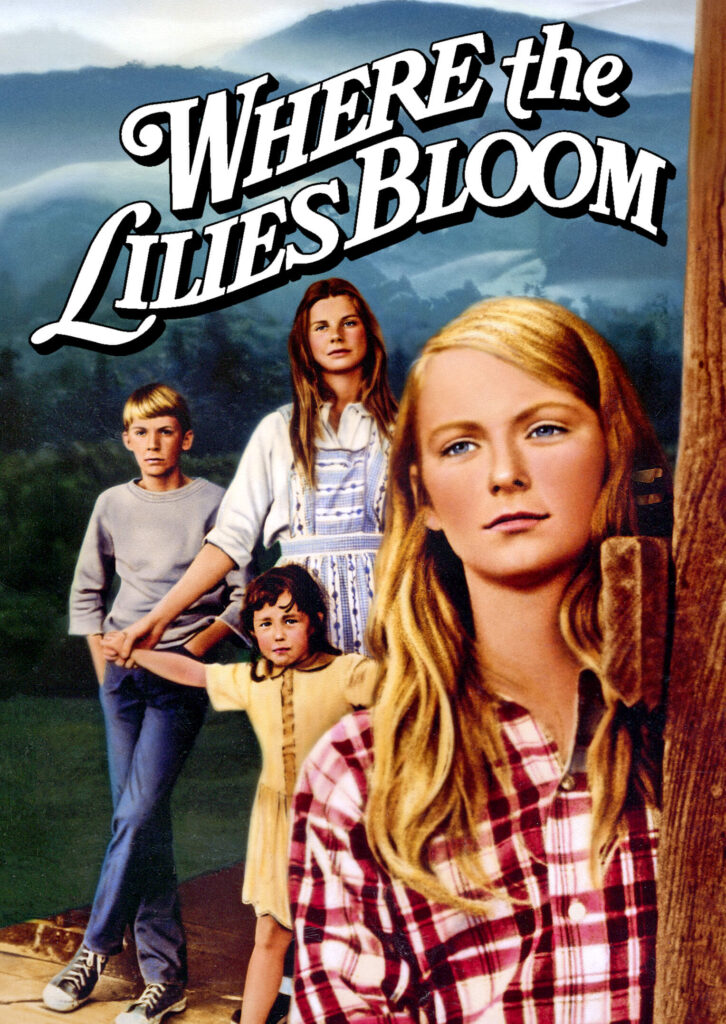

It was not a cultural climate in which a movie like Where the Lilies Bloom would make much of a splash, and it didn’t. Despite nice reviews, modest box-office success, and a connection to TV series The Waltons at the height of its popularity (its creator Earl Hamner Jr. wrote the adapted screenplay), this starless little film co-produced by Robert Radnitz and toy manufacturer Mattel soon disappeared. Kino Lorber’s new release to DVD and Blu-ray is, apparently, the first time it’s been available in any home format since fairly early VHS days.

Though not the kind of urban “gritty” we usually associate now with the best of US ’70s cinema, there are reasons to rank Lilies alongside some of that era’s hitherto neglected, recently re-appraised minor classics. It’s a warm but unsentimental story whose character is very much taken from that of heroine Mary Call (Julie Gholson), a flinty, piccolo-thin, pigtailed 14-year-old who’s just naturally the leader of a clan that’s lived in this particular Great Smoky Mountains valley for over two centuries.

Now they’re boiled down to sickly Roy Luther (Rance Howard, Ron’s father) and his four children, whose mother died four years ago. In addition to Mary Call, there’s pretty, nurturing eldest Devola (Jan Smithers), who’s not the sharpest tool in the shed; Romey (Matthew Burril), about 12, and five-year-old Ima Dean (Helen Harmon). Their scraping by has gotten more threadbare; between his poor health and worse financial sense, Roy has had to surrender the Luthers’ longtime property to the bank, which sold it to comparatively prosperous townie Kiser Pease (Harry Dean Stanton). He’s let them stay as sharecroppers, but that indignity rankles, as does Kiser’s fumbling romantic interest in Devola.

The only one in this lot old enough and sensible enough to take charge, Mary Call (who, like The Waltons’ John-Boy, has a nascent gift for writing) does so in the face of Roy Luther’s decline. When he dies (presumably of tuberculosis), she is the mastermind who must keep them all fed and together, lest they be scattered as orphans to the dread “County Home.” This involves increasingly elaborate deceptions, as well as generating income by wildcrafting (gathering herbs to sell for “old-timey remedies” now back in vogue). She must also honor her vow to keep Kiser Pease and Devola well-separated, even though he generally does his best to be helpful. Keeping this houseful of children afloat is hard work that her siblings eventually rebel against, while Mary Call herself chafes under the self-imposed pressure.

The source material was a Newberry Award-winning YA novel by Vera and Bill Cleaver, and producer Radnitz assembled its screen version with the same care he had the similar Sounder (also about a sharecropping family) two years before. William A. Graham, a prestigious longtime television director who made relatively few feature films, was hired to shoot on North Carolina rural locations where most of the cast was found, too. A major exception was Stanton, who’d already been working for two decades in mostly bit parts. He’s a joy here; Kiser Pease was one of his first great roles.

But Julie Gholson, who got a Golden Globe nomination for her screen debut, was just a local teen ultimately chosen from some 640 auditioning candidates. She never acted again (she’s reportedly executive director of an Alabama charity organization now), which somehow makes Mary Call all the more perfect a creation. Stubborn, pushy, fast-thinking, frequently just a hair’s-breadth short of complete exasperation, she is one of the movies’ great juvenile heroines, entirely winning without being conventionally “sweet” or “cute” in the least.

The same terms apply to Lilies as a whole: Most often striking a tone of rambunctious but not broad good humor, it is touching yet never maudlin or tear-jerking. The air of authenticity has kept it from seeming dated, in style or performance. There’s a fine bluegrassy score from Earl Scruggs, erstwhile of Flatt & Scruggs, famous for the Beverly Hillbillies theme. If the photography of the Watauga County countryside in northwesternmost NC by Indonesia-born Urs Furrer (who also shot the original Shaft, and strangely died one year later at age 40) doesn’t quite pop with verdant greens as I remember from 1974, well, it’ll do—probably nobody was busy preserving this film’s negative as they should have over the last half-century. Extras, alas, are slim, but having Where the Lilies Bloom back in circulation is enough.

Among the more intriguing new releases this weekend (we’ll get to Nope early next week), all of them are also female-driven narratives, and half are from women directors as well:

My Donkey, My Lover & I

If the Luther clan illustrate time-tested ways of living off the land, the hapless heroine in Caroline Vignal’s French comedy demonstrates no such knowhow whatsoever. Parisienne Antoinette (Laure Calamy) is a fifth-grade teacher already living rather recklessly via a torrid affair with the father (Benjamin Lavernhe) of one of her students. When she discovers he’s going off on a family vacation rather than spending more time with her, she impulsively books a solo hiking excursion in the mountainous Cevennes region—where, “coincidentally,” he will be with his wife and child.

This is a bad idea for many reasons, not least being that Antoinette’s experience of the outdoors has probably previously been limited to seating at cafes. Thinking it’s what “everyone does” (only to discover almost no one does), she has also booked a gear-carrying donkey, thus complicating her trek further by adding one very stubborn beast named Patrick.

Antoinette is frivolous, garrulous, over-emotional, a little crazy—we, like Patrick, are not at all sure at first we want to spend a week (or even 97 minutes) with her. But this scenic tale, very loosely inspired by Robert Louis Stevenson’s Cevennes travel memoir 140 years ago, grows on you. Not only is it the perfect vicarious-escape fare for those stuck staycationing this summer, it is also at times extremely funny—I doubt the entirety of the Francis the Talking Mule series ever eked quite so much comedic mileage out of well-timed brays as Vignal does here. It opens Fri/22 at the Opera Plaza.

Clara Sola

Romance is also a problem for the title figure in Nathalie Alvarez Mesen’s first feature. Clara (Wendy Chinchilla Araya) is a 40-year-old woman living in a remote Costa Rican village with her devoutly religious mother, a motherless teenage niece, and a white horse named Yuca. It is the latter who understands her best, perhaps—or at least judges her least. Among fellow bipeds, Clara is viewed as a simpleton, treated like an errant child, her crooked spine lending a sort of Quasimodo otherness. But her hitherto dormant sexuality stirs with the arrival of handsome young Santiago (Daniel Castaneda Rincon), who sometimes borrows Yuca for visiting tourists’ use. This new aspect to Clara’s personality is greeted with something like horror by loved ones, creating an internal schism that has literally seismic repercussions.

An allegorical statement about nature, repression, faith and eros, Clara Sola wraps its enigmatic narrative in lush atmospherics, making for an experience akin to an al fresco hot tub soak—something unwinding. Not everything in it works, or is pointed, but it’s a striking debut. It opens Fri/22 at the Roxie.

Moloch

The supernatural elements that hover on Clara Sola’s periphery, mostly out of sight, are much more central to—and malevolent in—Nico van den Brink’s first directorial feature. A village on a peat bog in the Netherlands’ north country is home to Betriek (Sallie Harmsen), who’s reluctantly returned here to raise a young daughter after her husband’s death. So they’ve moved in with her parents, who remain under the same roof she was raised in, but otherwise seem to live wholly separate lives.

That, however, isn’t what troubles Betriek. Instead, it’s something about the spirit of the place itself, rooted in buried childhood trauma (her grandmother was murdered while she was in the house), and now curiously roused by visiting archaeologists’ discovery of a miraculously preserved female corpse in the bog.

Moloch is folk horror of a witchy, matriarchal, evil-secret-passed-down-for-generations ilk, well-acted and handsomely crafted but over-familiar nonetheless. It’s not suspenseful enough for this type of enterprise, with too many rote jump scares and no great fascination to the murky mythology hinted at. Still, it’s above-average for the genre, and has a decent twist ending. It’s available on specialty streaming platform Shudder as of Thurs/21.

My Name Is Sara

The horrors are all too real-world in this fact-based drama based on survivor testimony by one Sara Goralnik many decades after the events depicted. Fleeing a September 1942 massacre of Jews that claims their parents, 13-year-old Sara (Zuzanna Surowy) soon separates from her brother to pass as a Gentile on the other side of the Poland-Ukraine border.

Dubbing herself “Manya” and claiming to be a runaway from an unhappy home, she begs work from a Ukrainian farming family. They take her in, albeit grudgingly, and with considerable suspicion unalleviated by the vicious discord between husband (Eryk Lubos) and wife (Michalina Olszanka). Then there’s the constant threat of being found out, as occupying Nazis continue to persecute remaining Jews while fighting partisan resistance fighters—and every side seems to view the farm as available plunder.

It’s an inherently tense, engrossing story, somewhat reminiscent of Europa Europa, although undercut by variable performances (particularly a stilted lead one) and an occasionally heavy-handed approach. While shot on location with actors of appropriate ethnic and national backgrounds, they mostly speak their lines in strained English, which is simply awkward. Director Steven Oritt’s film is not the most artfully told depiction of Jewish survival during WW2, but the power of the tale itself (whose real-life protagonist eventually emigrated to the US, passing away at age 88 just four years ago) ultimately makes it worthwhile. My Name is Sara opens Fri/22 at the Opera Plaza.