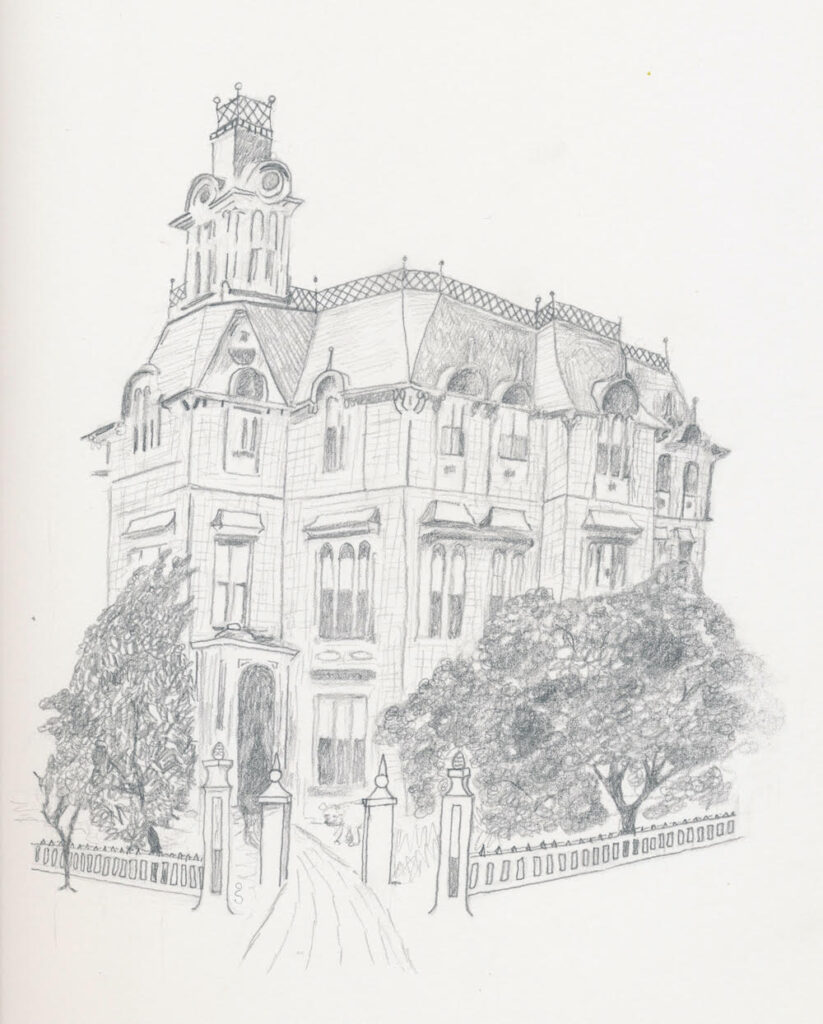

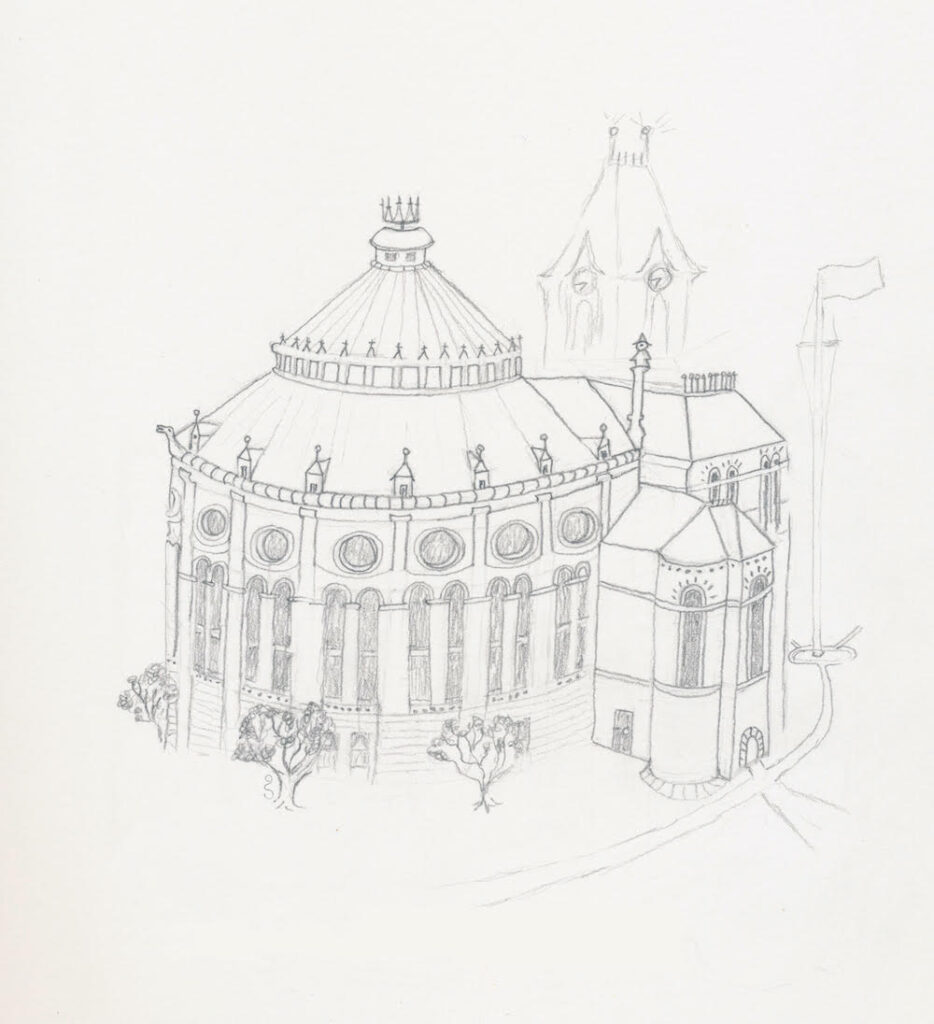

Superstar architect Julia Morgan would go on to design more than 700 buildings including many YWCAs, the Berkeley City Club, and most famously, Hearst Castle. But she was born in San Francisco, later moving with her family to Oakland, and attending University of California, Berkeley. Afterwards, Morgan attended the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, becoming the first woman to do so. She racked up several such firsts, including the distinction of being the first woman in California to earn an architecture license, and the first woman to win the American Institute of Architects’ highest honor.

For most of her followers, it was during Morgan’s time in Paris when her story starts, according to Berkeley author Susan J. Austin. But in her newly released historical novel, Drawing Outside the Lines (SparkPress, $12.95), Austin takes a look at the notoriously private architect’s life before that era. In its pages, Morgan takes a mechanical drawing class at Oakland High School, roller skates around town, refuses her mother’s wish that she become a debutante. She faces disparagement from the male colleagues (and sometimes teachers) in her mechanical engineering classes at Cal, as well as support and encouragement from her sorority sisters.

The author decided to write the book after a little girl asked her why Morgan became an architect. To answer this query meant wading through a lot of books on the expectations of girls in Victorian families, plus old newspapers, Morgan’s letters, and her college yearbooks. Fortunately, Austin loves research.

The first breakthrough, the author says, was in finding the letters of the Kennedy Library at California Polytechnic State University’s Julia Morgan collection. Some of them had been written by Morgan’s mother while living in Brooklyn Heights, staying with her parents while Morgan’s father was still in California.

“Those letters told me a lot about family dynamics, told me about how they viewed young Julia,” Austin told 48hills. “[They] told me about how Julia got so sick, and how it affected her ear, which we knew as an adult was an issue for her [Morgan had scarlet fever, which resulted in ear infections]. I was able to get some back story of these early years when Julia Morgan was six to seven years old. They’re just a treasure.”

Austin says Morgan’s father is often dismissed as a “financial failure,” but she thinks there was far more to him. In the book, she portrays his excitement about taking his daughter to get the tools for her mechanical drawing class. He was involved with education, Austin says, and she includes in her novel the story of his successful run for school board director. The newspapers from that time were helpful in providing some of his campaign speeches.

“He had a vision for schools, and what kids should be doing in schools,” she said. “He thought that they should be learning how to work with their hands.”

Austin combined research with her own imagination to create a fictional story of Morgan’s high school and college years.

She asked architectural historian and Julia Morgan expert Karen McNeill to look at an early draft. If McNeill had felt it was too far-fetched, Austin would have abandoned the project.

But McNeill told her what she had created was plausibly grounded in research, even agreeing that Morgan’s father made for an interesting character.

Austin also read the letters between Morgan and her cousin, architect Pierre LeBruin, written when Morgan was at École des Beaux-Arts. She imagines Morgan, as a little girl in 1883, going to see the newly built Brooklyn Bridge with LeBruin, and letters they had sent previously during Morgan’s childhood and college days.

Austin also had help imagining the childhood friendship of Morgan and Mary McLean, who both became members of Kappa Alpha Theta at UC Berkeley. At UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library, Austin found an oral history McLean recorded at 90 recounting roller skating, fence walking, and tree climbing. In Drawing Outside the Lines, McLean and Morgan do those things together as girls.

“I knew Julia Morgan was a very athletic child, unafraid of heights,” Austin said. “I could imagine that she would be just as eager as Mary to do these things, especially with a friend—and from a writing point of view, I did need a friend for Julia Morgan.”

In old newspapers, Austin also found several articles about Mollie E. Connors, Morgan’s Oakland High mechanical arts teacher, as well as a story about a tandem bike ride that future writer and art collector Gertrude Stein, another student at Oakland High, participated in (presumably finding some “there” in her town.) Austin makes Morgan and Stein partners on the ride in the novel. Another cameo in the book is Frank Norris (author of The Octopus) who was at UC Berkeley with Morgan and wrote the pageant for Morgan’s graduating class of 1894.

Austin says she made charts and graphs plotting out the chronology of Morgan’s life, and what was going on in Oakland and in the world during that time. Another source she used was the Blue & Gold Cal yearbooks. Photos of Morgan taken in Kappa Alpha Theta also hang on Austin’s bulletin board.

“The beauty of Julia Morgan being in a sorority is it was probably one of the first times she had a group of women who were smart and driven the way she was,” Austin said, adding how much fun she had finding out about Morgan’s persistence in achieving her ambition.

“I grew to really admire this person and what she endured and became.”

Order Drawing Outside the Lines here.