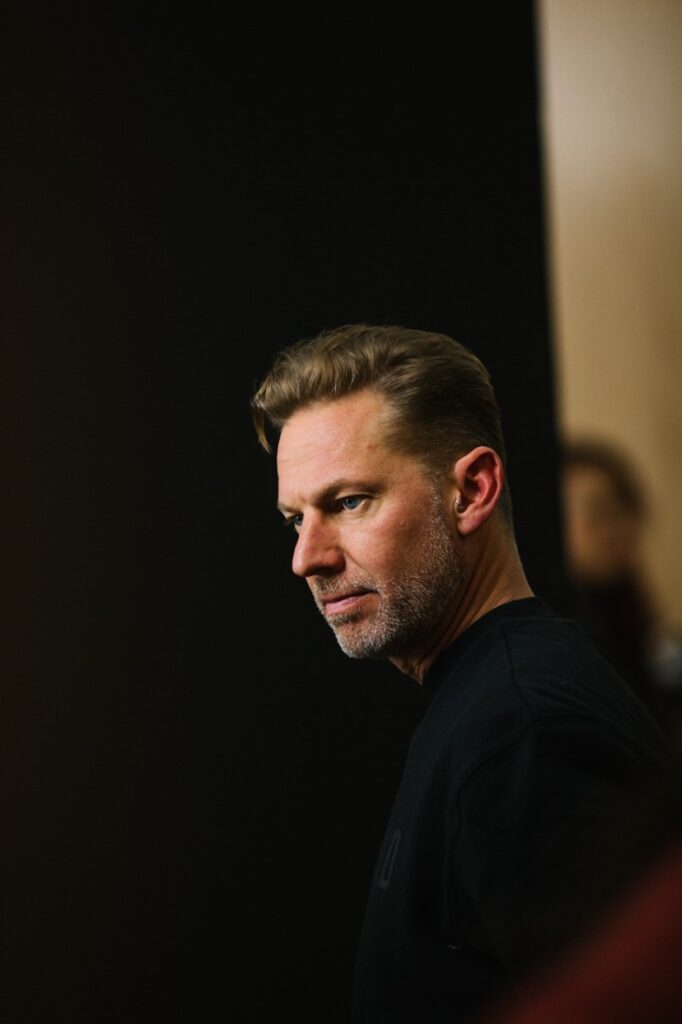

Sculptor Peter St. Lawrence believes that making art is an act of accountability. It allows him to lose, then find himself again—a reminder of why he is here.

“Art is something that I need to do, the way a cattle dog needs to herd,” St. Lawrence told 48hills.

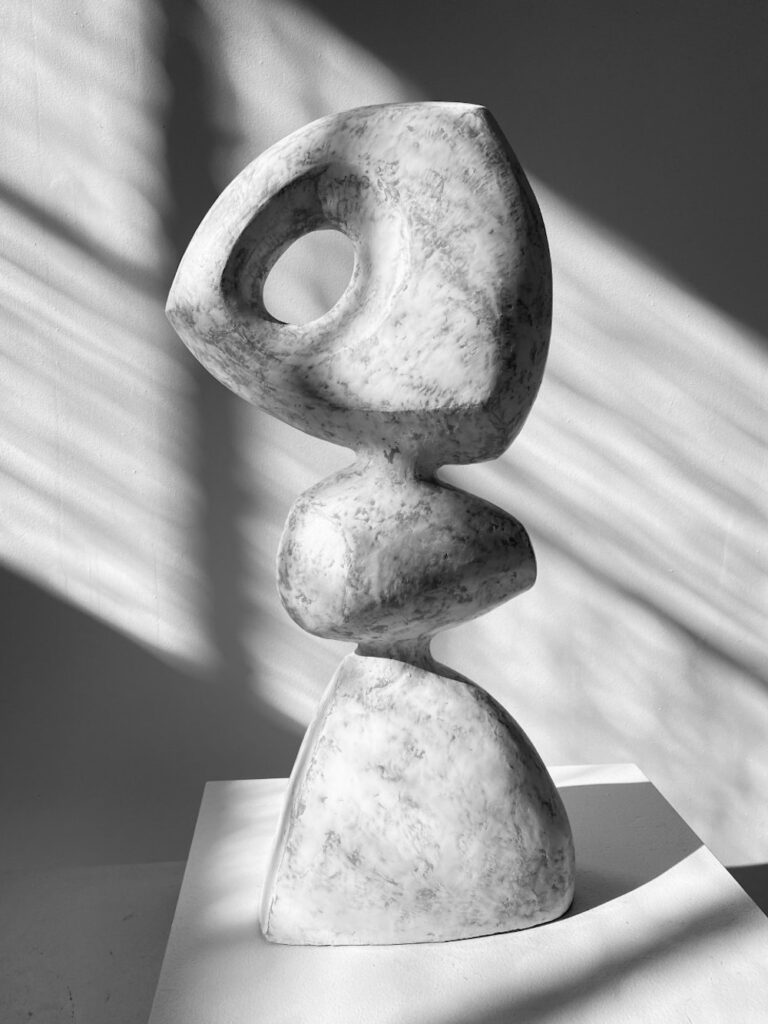

A 2001 graduate of California College of the Arts, St. Lawrence creates sensual, organic forms that are pleasingly minimal. There is a poetic resonance in both his work and in the words he uses in its description. St. Lawrence believes that some people are born artists, pulled to create like the force of a tide. He said that it is important to remember that practicing art is not selfish, but actually responsible and giving, an important contribution to the world.

“It is an enormous commitment of time and resources to pursue an art practice, but it can be hard to justify in a world that does not often reward artists with financial prowess,” he commented.

Through developing his discipline, St. Lawrence encounters moments of “pure bottled lightning,” his term for the connections his work makes with others. Art provides him with the opportunity to tap into something infinitely bigger than himself—a dipping of a toe into a river of ancient, universal consciousness—which he finds absolutely thrilling, and so powerful that it keeps him coming back for more. His process isn’t about method or devices. He doesn’t approach content directly, but has learned to trust it.

“I’m always searching for a way in. Once I’ve arrived at a surprising relationship of shapes and commit to exploring it, I become engaged in a dialogue with form and material that guides my hands,” he said.

This intuitive approach leaves room for an emotional potency with a certain degree of ambiguity that he finds necessary. He’s looking for opportunities to transcend dry, flat ideas and provide deep, textured, nuanced experiences. He honors the work by allowing it to quietly stand there and invite us in. St. Lawrence believes that his role as an artist is to show people something they didn’t know they needed to see. He gets there by being unapologetically bold and honest with himself.

“Art is an opportunity to go somewhere completely new, and find a way of connecting that is more intuitive than the limitations of our vastly inadequate alphabet. There are invisible forces affecting us every day that we don’t even have words for,” he said.

Early in the morning, St. Lawrence leaves his home in Pill Hill and rides his bike around Lake Merritt to his studio in the Little Saigon neighborhood of Oakland. His space occupies an abandoned auto parts depot in a building that St. Lawrence says you could go past 500 times without ever noticing.

After entering through a white-walled gallery into a warren of studios belonging to a diverse group of artists, St. Lawrence gets to work. The space contains a depth of beauty for the artist, a place where talent is freed in a building that hums with creative potential. His studio is in the back, adjacent to a giant barn door that opens to an enclosed courtyard full of potted cactuses.

“The moment of opening that barn door is critical to my process. There is something sacred to me about the quality of natural light in the morning,” he said.

At work, St. Lawrence minimizes mental clutter, preserving an inner quiet and sense of wonder. He won’t look at social media or the news until after he’s made art for a few hours, seeking a pure experience that emerges from within that is untainted by the external world.

“I try to ensure that my practice is intentional and not reactionary. Art in its most powerful form is the leading edge of thought rather than a follower of trends, a reaction to politics, or a placation to capitalism,” he said.

Each sculpture begins with a sketch or a watercolor. Its inspiration can come from anywhere: a dream, a color, a bird. Working and reworking a drawing, he sculpts on the page until intriguing relationships of shape, line, or color come into focus. This is the jumping off point for his three-dimensional work.

“The final piece will never look exactly like the drawing. I leave room for improvisation, so I remain completely engaged with the piece,” he said.

Most of St. Lawrence’s sculptures are built one handful of clay at a time, from the base up, providing the opportunity to add or subtract. Because the drawing only shows one side of the sculpture, he explores the same notion in three dimensions and moves around the piece, making decisions in the moment. A piece is finished when his hand no longer reaches out to resolve anything.

His interest in sculpture began with portraiture, making busts of friends, marionettes that now dangle from his studio ceiling, and life-size statues busy with symbolism, color, materials, texture, and technique. But about five years ago, everything went completely abstract.

While doing some ceramic fabrication for a well-known painter, St. Lawrence made a transition. As the relationship matured into a fruitful collaboration, he was asked to provide bigger, more expressive forms. Somewhere in the middle of that process, St. Lawrence pondered creating simple abstract forms, so he started closing pots off on the top. One day, a studiomate walked by and asked him what he was working on. When St. Lawrence shared his new work, he was told there was a lot more Peter St. Lawrence coming through.

“My hair stood up. He was right. For the first time in my life, those simple abstract forms were enough for me,” he said.

It felt like a thousand doors opened at once. The figurative subject matter that he had been using was no longer necessary, replaced with the idea of meaningful creation.

“When I stopped trying to put every idea into every piece, the work became stronger. The more confidence I have in the restraint, the more pure it becomes,” he said.

As thrilling as it was for the artist to depart from the figure, there remains something very corporal about his forms. The proportions, the curves, and even the scale make the sculptures feel like people. An early pottery teacher of his told him that everything St. Lawrence makes looks like it wants to get up and walk around.

The last few years have impacted his art deeply. While sheltering-in-place in a cabin in the Feather River Valley, his work got microscopic, becoming watercolor landscape paintings the size of postage stamps and sculptures the size of chess pieces. When he returned to his Oakland studio, his work swelled, becoming monumental.

He was commissioned to create a 60-foot-long undulating sculpture to hang from the ceiling of new Uptown Oakland restaurant Occitania. The work is composed of around 30 gilded pieces that rise and fall and eddy in the dining room.

“The components have a feeling of rocks shaped by water or trees shaped by wind—something that has been refined by erosion—symbolizing the beauty of resilience,” he said. “That’s about right for a restaurant conceived during shelter-in-place.”

In March, St. Lawrence completed a new series for a show at Oakland’s Slate Contemporary that will be on display through April. Sculptures that stack into tall, vertical forms freed him from the limitations of his kiln, removing a dimensional boundary that always subconsciously weighed on him.

“I can feel the freedom in the work. There is a quality of rising up and defying gravity,” he said.

Apart from sculpture, St. Lawrence also does set design, set decoration, and prop styling for photography and video. With a background in floral design, he is often sought out when a set requires plants. As a sculptor, St. Lawrence says flowers have taught him “through their exquisite materiality.” Plus, the collaborative nature of these production endeavors is uniquely satisfying, providing a particular kind of human connection that he craves.

St. Lawrence is a proponent of keeping his hands moving, knowing that inspiration arrives on its own terms. And when it does, the importance of having the space, the materials, and the tools to take advantage of the opportunity is paramount. His advice for artists—or as a general rule for life—is this:

“Finish every piece you start, even when it becomes difficult and you hate it, and it’s not fun anymore. The more you discover ways to resolve things and make them feel finished, the more kindling you have when the spark of inspiration arrives,” he said.

For more information, visit Peter St. Lawrence’s website and Instagram.