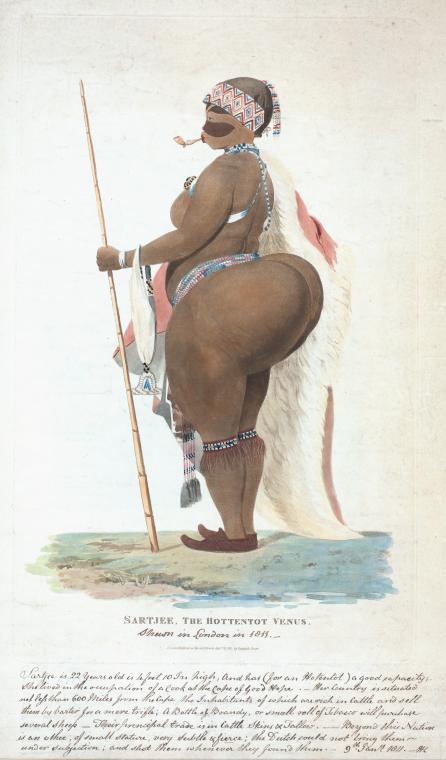

The moment I knew the Museum of the Diaspora was putting on a show about perceptions of Black women throughout the ages, I knew there would have to be something relating to Sarah Baartman, often alluded to by the racist moniker “Hottentot Venus.” Baartman’s overgrown physical features—particularly, her rear end—made her a sideshow curiosity in pre-Victorian Europe. So much so that after her death, her body parts were amputated from her corpse and put on display like spoils of war. A Black woman was literally reduced to disembodied pieces for the titillation of European spectators.

Sure enough, the Aindrea Emelife-curated Black Venus (through August 20 at MoAD) is an exhibition in which Baartman’s life, in Emelife’s own words, “informs the way Black women are seen by the world.” Although Baartman’s literal likeness is only seen briefly (inside a display case, of all things), it isn’t hard to draw a clear line from her objectification to tennis player Caroline Wozniacki mocking of Serena Williams’ ample figure. (Although the two players are friends, Wozniacki’s imitation fit into a long, racist history of the Williams sisters’ bodies getting more coverage than their top-notch tennis skills.)

Sometimes, the Baartman allusions are overt, such as with the monochrome photo “Hottentot Venus” by the ever-controversial Renee Cox, in which a model recreates Baartman’s figure through the use of costume prosthetics. More subtle examples include Carla Williams’ untitled photos (also monochrome) of full-figured Black women taken in-profile. Both seek accountability for the world’s objectification of Black women, whilst allowing Black women themselves to remix the narrative in their own vision. Both are examples of when it actually works.

Less effective are pieces like Frida Orupabo’s “Bottle and Gun,” a collage featuring cut-outs of its titular objects, as well as the face of an African tribeswoman, a speculum, a high-heeled shoe, a baby’s bottle, and a rear-end from the side. Not arranged so much as just presented together, the piece is a reminder of how it’s one thing to not pander and obviously connect the dots for an observer, but it’s another to not go the extra step.

More successful is Deana Lawson’s “2 Live Crew Video Girl,” a photo of a (CRT?) television featuring a dancer in a video for the titular late-‘80s rap crew. The piece hangs next to an untitled collage by Kara Walker in which the cut-out image of a Black woman’s sexualized body had the head ripped away and replaced with that of the Sphinx of Giza.

Granted, not every piece can have the balance as those of Carrie Mae Weems, some of which are included here. Her red-tinted photos inside black-framed orbs give the impression of looking through a microscope to highlight how Black women have gone from the white world’s nurturing “Mammy” figure to an object of terror (the latter just so happening to correspond with emancipation—go figure.)

One of the more powerful works is the audio-visual piece in the Toni Rembe Theatre. Yétundé Olagbaju’s two-part video piece, “How to Erase,” presents itself as a collection of images and clips on an open Macintosh desktop. They include ancient yoni statues and “mammy” characters from the “Tom & Jerry” episode “Push-Button Kitty”. Both pieces feature rather abstract geometric patterns that occasionally move. In an isolated window is a tone poem written in real time, starting with, “Begin with memory of the thing …” and eventually concluding with, “In order to erase, I behold your complexities.”

I dare say that line lingered with me more than any of the images themselves. The thing about stereotypes is that it’s easy to say they aren’t true (and a lot of them aren’t), but more important is the fact that they’re oversimplified. Reducing a person to a set of traits—or body parts—frees the observer from considering the observed as a complex human being.

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

The power of Emelife’s exhibit lies in casting a wide net and exploring the nuances of the spectrum that represents Black women, both the labels forced upon them and those they embrace by choice. It creates a world beyond white women posting “Yaaas queen!” memes on social media only to throw Black women under the bus at the first opportunity. (Lookin’ at you, Tina Fey and Lena Dunham.) It surrounds the viewer with various shades of Black femininity that are often lost in the casual misogynoir of mainstream media. Drake can mock Megan Thee Stallion’s body and her being shot, but publications will still promote his albums; so too will Chris Brown continue to abuse his (often Black) girlfriends, so long as the Kelly Rowlands and Chlöe Baileys of the world are there to defend him.

The exhibit isn’t perfect. The most powerful and compelling pieces make it all the more apparent which ones didn’t put forth as much effort. What’s more, despite the welcome presence of work by artists like Olagbaju and Zanele Muholi, whose “Miss (Black) Lesbian” photo series is on display, representation of queer and trans spectrums in Black femininity are not overly visible in Black Venus. Given how such identities were actively muted throughout history, their seemingly diminished presence in a contemporary exhibit sticks out like a sore thumb.

Overall, the exhibit hits the right note, comparing and contrasting images and narratives created about Black women with those created by them. If anything, it makes one all the more hopeful they’ll see more of the latter.

BLACK VENUS runs through August 20. Museum of the African Diaspora, SF. Tickets and more info here.